Hilbert space

Template:Short description Template:For

In mathematics, a Hilbert space (named for David Hilbert) generalizes the notion of Euclidean space. It extends the methods of linear algebra and calculus from the two-dimensional Euclidean plane and three-dimensional space to spaces with any finite or infinite number of dimensions. A Hilbert space is a vector space equipped with an inner product operation, which allows lengths and angles to be defined. Furthermore, Hilbert spaces are complete, which means that there are enough limits in the space to allow the techniques of calculus to be used. A Hilbert space is a special case of a Banach space.

Hilbert spaces were studied beginning in the first decade of the 20th century by David Hilbert, Erhard Schmidt, and Frigyes Riesz. They are indispensable tools in the theories of partial differential equations, quantum mechanics, Fourier analysis (which includes applications to signal processing and heat transfer), and ergodic theory (which forms the mathematical underpinning of thermodynamics). John von Neumann coined the term Hilbert space for the abstract concept that underlies many of these diverse applications. The success of Hilbert space methods ushered in a very fruitful era for functional analysis. Apart from the classical Euclidean vector spaces, examples of Hilbert spaces include spaces of square-integrable functions, spaces of sequences, Sobolev spaces consisting of generalized functions, and Hardy spaces of holomorphic functions.

Geometric intuition plays an important role in many aspects of Hilbert space theory. Exact analogs of the Pythagorean theorem and parallelogram law hold in a Hilbert space. At a deeper level, perpendicular projection onto a linear subspace plays a significant role in optimization problems and other aspects of the theory. An element of a Hilbert space can be uniquely specified by its coordinates with respect to an orthonormal basis, in analogy with Cartesian coordinates in classical geometry. When this basis is countably infinite, it allows identifying the Hilbert space with the space of the infinite sequences that are square-summable. The latter space is often in the older literature referred to as the Hilbert space.

Definition and illustration

Motivating example: Euclidean vector space

One of the most familiar examples of a Hilbert space is the Euclidean vector space consisting of three-dimensional vectors, denoted by Template:Math, and equipped with the dot product. The dot product takes two vectors Template:Math and Template:Math, and produces a real number Template:Math. If Template:Math and Template:Math are represented in Cartesian coordinates, then the dot product is defined by

The dot product satisfies the properties[1]

- It is symmetric in Template:Math and Template:Math: Template:Math.

- It is linear in its first argument: Template:Math for any scalars Template:Mvar, Template:Mvar, and vectors Template:Math, Template:Math, and Template:Math.

- It is positive definite: for all vectors Template:Math, Template:Math, with equality if and only if Template:Math.

An operation on pairs of vectors that, like the dot product, satisfies these three properties is known as a (real) inner product. A vector space equipped with such an inner product is known as a (real) inner product space. Every finite-dimensional inner product space is also a Hilbert space.[2] The basic feature of the dot product that connects it with Euclidean geometry is that it is related to both the length (or norm) of a vector, denoted Template:Math, and to the angle Template:Mvar between two vectors Template:Math and Template:Math by means of the formula

Multivariable calculus in Euclidean space relies on the ability to compute limits, and to have useful criteria for concluding that limits exist. A mathematical series consisting of vectors in Template:Math is absolutely convergent provided that the sum of the lengths converges as an ordinary series of real numbers:[3]

Just as with a series of scalars, a series of vectors that converges absolutely also converges to some limit vector Template:Math in the Euclidean space, in the sense that

This property expresses the completeness of Euclidean space: that a series that converges absolutely also converges in the ordinary sense.

Hilbert spaces are often taken over the complex numbers. The complex plane denoted by Template:Math is equipped with a notion of magnitude, the complex modulus Template:Math, which is defined as the square root of the product of Template:Mvar with its complex conjugate:

If Template:Math is a decomposition of Template:Mvar into its real and imaginary parts, then the modulus is the usual Euclidean two-dimensional length:

The inner product of a pair of complex numbers Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar is the product of Template:Mvar with the complex conjugate of Template:Mvar:

This is complex-valued. The real part of Template:Math gives the usual two-dimensional Euclidean dot product.

A second example is the space Template:Math whose elements are pairs of complex numbers Template:Math. Then an inner product of Template:Mvar with another such vector Template:Math is given by

The real part of Template:Math is then the four-dimensional Euclidean dot product. This inner product is Hermitian symmetric, which means that the result of interchanging Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar is the complex conjugate:

Definition

A Template:Em is a real or complex inner product space that is also a complete metric space with respect to the distance function induced by the inner product.[4]

To say that a complex vector space Template:Math is a Template:Em means that there is an inner product associating a complex number to each pair of elements of Template:Math that satisfies the following properties:

- The inner product is conjugate symmetric; that is, the inner product of a pair of elements is equal to the complex conjugate of the inner product of the swapped elements: Importantly, this implies that is a real number.

- The inner product is linear in its first[nb 1] argument. For all complex numbers and

- The inner product of an element with itself is positive definite:

It follows from properties 1 and 2 that a complex inner product is Template:Em, also called Template:Em, in its second argument, meaning that

A Template:Em is defined in the same way, except that Template:Math is a real vector space and the inner product takes real values. Such an inner product will be a bilinear map and will form a dual system.Template:Sfn

The norm is the real-valued function and the distance between two points in Template:Math is defined in terms of the norm by

That this function is a distance function means firstly that it is symmetric in and secondly that the distance between and itself is zero, and otherwise the distance between and must be positive, and lastly that the triangle inequality holds, meaning that the length of one leg of a triangle Template:Math cannot exceed the sum of the lengths of the other two legs:

This last property is ultimately a consequence of the more fundamental Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, which asserts with equality if and only if and are linearly dependent.

With a distance function defined in this way, any inner product space is a metric space, and sometimes is known as a Template:Em.[5] Any pre-Hilbert space that is additionally also a complete space is a Hilbert space.[6]

The Template:Em of Template:Math is expressed using a form of the Cauchy criterion for sequences in Template:Math: a pre-Hilbert space Template:Math is complete if every Cauchy sequence converges with respect to this norm to an element in the space. Completeness can be characterized by the following equivalent condition: if a series of vectors converges absolutely in the sense that then the series converges in Template:Math, in the sense that the partial sums converge to an element of Template:Math.[7]

As a complete normed space, Hilbert spaces are by definition also Banach spaces. As such they are topological vector spaces, in which topological notions like the openness and closedness of subsets are well defined. Of special importance is the notion of a closed linear subspace of a Hilbert space that, with the inner product induced by restriction, is also complete (being a closed set in a complete metric space) and therefore a Hilbert space in its own right.

Second example: sequence spaces

The sequence space Template:Math consists of all infinite sequences Template:Math of complex numbers such that the following series converges:[8]

The inner product on Template:Math is defined by:

This second series converges as a consequence of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality and the convergence of the previous series.

Completeness of the space holds provided that whenever a series of elements from Template:Math converges absolutely (in norm), then it converges to an element of Template:Math. The proof is basic in mathematical analysis, and permits mathematical series of elements of the space to be manipulated with the same ease as series of complex numbers (or vectors in a finite-dimensional Euclidean space).[9]

History

Prior to the development of Hilbert spaces, other generalizations of Euclidean spaces were known to mathematicians and physicists. In particular, the idea of an abstract linear space (vector space) had gained some traction towards the end of the 19th century:[10] this is a space whose elements can be added together and multiplied by scalars (such as real or complex numbers) without necessarily identifying these elements with "geometric" vectors, such as position and momentum vectors in physical systems. Other objects studied by mathematicians at the turn of the 20th century, in particular spaces of sequences (including series) and spaces of functions,[11] can naturally be thought of as linear spaces. Functions, for instance, can be added together or multiplied by constant scalars, and these operations obey the algebraic laws satisfied by addition and scalar multiplication of spatial vectors.

In the first decade of the 20th century, parallel developments led to the introduction of Hilbert spaces. The first of these was the observation, which arose during David Hilbert and Erhard Schmidt's study of integral equations,[12] that two square-integrable real-valued functions Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar on an interval Template:Math have an inner product

that has many of the familiar properties of the Euclidean dot product. In particular, the idea of an orthogonal family of functions has meaning. Schmidt exploited the similarity of this inner product with the usual dot product to prove an analog of the spectral decomposition for an operator of the form

where Template:Mvar is a continuous function symmetric in Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar. The resulting eigenfunction expansion expresses the function Template:Mvar as a series of the form

where the functions Template:Mvar are orthogonal in the sense that Template:Math for all Template:Math. The individual terms in this series are sometimes referred to as elementary product solutions. However, there are eigenfunction expansions that fail to converge in a suitable sense to a square-integrable function: the missing ingredient, which ensures convergence, is completeness.[13]

The second development was the Lebesgue integral, an alternative to the Riemann integral introduced by Henri Lebesgue in 1904.[14] The Lebesgue integral made it possible to integrate a much broader class of functions. In 1907, Frigyes Riesz and Ernst Sigismund Fischer independently proved that the space Template:Math of square Lebesgue-integrable functions is a complete metric space.[15] As a consequence of the interplay between geometry and completeness, the 19th century results of Joseph Fourier, Friedrich Bessel and Marc-Antoine Parseval on trigonometric series easily carried over to these more general spaces, resulting in a geometrical and analytical apparatus now usually known as the Riesz–Fischer theorem.[16]

Further basic results were proved in the early 20th century. For example, the Riesz representation theorem was independently established by Maurice Fréchet and Frigyes Riesz in 1907.[17] John von Neumann coined the term abstract Hilbert space in his work on unbounded Hermitian operators.[18] Although other mathematicians such as Hermann Weyl and Norbert Wiener had already studied particular Hilbert spaces in great detail, often from a physically motivated point of view, von Neumann gave the first complete and axiomatic treatment of them.[19] Von Neumann later used them in his seminal work on the foundations of quantum mechanics,[20] and in his continued work with Eugene Wigner. The name "Hilbert space" was soon adopted by others, for example by Hermann Weyl in his book on quantum mechanics and the theory of groups.[21]

The significance of the concept of a Hilbert space was underlined with the realization that it offers one of the best mathematical formulations of quantum mechanics.[22] In short, the states of a quantum mechanical system are vectors in a certain Hilbert space, the observables are hermitian operators on that space, the symmetries of the system are unitary operators, and measurements are orthogonal projections. The relation between quantum mechanical symmetries and unitary operators provided an impetus for the development of the unitary representation theory of groups, initiated in the 1928 work of Hermann Weyl.[21] On the other hand, in the early 1930s it became clear that classical mechanics can be described in terms of Hilbert space (Koopman–von Neumann classical mechanics) and that certain properties of classical dynamical systems can be analyzed using Hilbert space techniques in the framework of ergodic theory.[23]

The algebra of observables in quantum mechanics is naturally an algebra of operators defined on a Hilbert space, according to Werner Heisenberg's matrix mechanics formulation of quantum theory.[24] Von Neumann began investigating operator algebras in the 1930s, as rings of operators on a Hilbert space. The kind of algebras studied by von Neumann and his contemporaries are now known as von Neumann algebras.[25] In the 1940s, Israel Gelfand, Mark Naimark and Irving Segal gave a definition of a kind of operator algebras called C*-algebras that on the one hand made no reference to an underlying Hilbert space, and on the other extrapolated many of the useful features of the operator algebras that had previously been studied. The spectral theorem for self-adjoint operators in particular that underlies much of the existing Hilbert space theory was generalized to C*-algebras.[26] These techniques are now basic in abstract harmonic analysis and representation theory.

Examples

Lebesgue spaces

Lebesgue spaces are function spaces associated to measure spaces Template:Math, where Template:Math is a set, Template:Math is a σ-algebra of subsets of Template:Math, and Template:Math is a countably additive measure on Template:Math. Let Template:Math be the space of those complex-valued measurable functions on Template:Math for which the Lebesgue integral of the square of the absolute value of the function is finite, i.e., for a function Template:Math in Template:Math, and where functions are identified if and only if they differ only on a set of measure zero.

The inner product of functions Template:Math and Template:Math in Template:Math is then defined as or

where the second form (conjugation of the first element) is commonly found in the theoretical physics literature. For Template:Math and Template:Math in Template:Math, the integral exists because of the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, and defines an inner product on the space. Equipped with this inner product, Template:Math is in fact complete.[27] The Lebesgue integral is essential to ensure completeness: on domains of real numbers, for instance, not enough functions are Riemann integrable.[28]

The Lebesgue spaces appear in many natural settings. The spaces Template:Math and Template:Math of square-integrable functions with respect to the Lebesgue measure on the real line and unit interval, respectively, are natural domains on which to define the Fourier transform and Fourier series. In other situations, the measure may be something other than the ordinary Lebesgue measure on the real line. For instance, if Template:Math is any positive measurable function, the space of all measurable functions Template:Math on the interval Template:Math satisfying is called the [[Lp space#Weighted Lp spaces|weighted Template:Math space]] Template:Math, and Template:Math is called the weight function. The inner product is defined by

The weighted space Template:Math is identical with the Hilbert space Template:Math where the measure Template:Math of a Lebesgue-measurable set Template:Math is defined by

Weighted Template:Math spaces like this are frequently used to study orthogonal polynomials, because different families of orthogonal polynomials are orthogonal with respect to different weighting functions.[29]

Sobolev spaces

Sobolev spaces, denoted by Template:Math or Template:Math, are Hilbert spaces. These are a special kind of function space in which differentiation may be performed, but that (unlike other Banach spaces such as the Hölder spaces) support the structure of an inner product. Because differentiation is permitted, Sobolev spaces are a convenient setting for the theory of partial differential equations.[30] They also form the basis of the theory of direct methods in the calculus of variations.[31]

For Template:Math a non-negative integer and Template:Math, the Sobolev space Template:Math contains Template:Math functions whose weak derivatives of order up to Template:Math are also Template:Math. The inner product in Template:Math is where the dot indicates the dot product in the Euclidean space of partial derivatives of each order. Sobolev spaces can also be defined when Template:Math is not an integer.

Sobolev spaces are also studied from the point of view of spectral theory, relying more specifically on the Hilbert space structure. If Template:Math is a suitable domain, then one can define the Sobolev space Template:Math as the space of Bessel potentials;[32] roughly,

Here Template:Math is the Laplacian and Template:Math is understood in terms of the spectral mapping theorem. Apart from providing a workable definition of Sobolev spaces for non-integer Template:Math, this definition also has particularly desirable properties under the Fourier transform that make it ideal for the study of pseudodifferential operators. Using these methods on a compact Riemannian manifold, one can obtain for instance the Hodge decomposition, which is the basis of Hodge theory.[33]

Spaces of holomorphic functions

Hardy spaces

The Hardy spaces are function spaces, arising in complex analysis and harmonic analysis, whose elements are certain holomorphic functions in a complex domain.[34] Let Template:Math denote the unit disc in the complex plane. Then the Hardy space Template:Math is defined as the space of holomorphic functions Template:Math on Template:Math such that the means remain bounded for Template:Math. The norm on this Hardy space is defined by

Hardy spaces in the disc are related to Fourier series. A function Template:Math is in Template:Math if and only if where

Thus Template:Math consists of those functions that are L2 on the circle, and whose negative frequency Fourier coefficients vanish.

Bergman spaces

The Bergman spaces are another family of Hilbert spaces of holomorphic functions.[35] Let Template:Math be a bounded open set in the complex plane (or a higher-dimensional complex space) and let Template:Math be the space of holomorphic functions Template:Math in Template:Math that are also in Template:Math in the sense that where the integral is taken with respect to the Lebesgue measure in Template:Math. Clearly Template:Math is a subspace of Template:Math; in fact, it is a closed subspace, and so a Hilbert space in its own right. This is a consequence of the estimate, valid on compact subsets Template:Math of Template:Math, that which in turn follows from Cauchy's integral formula. Thus convergence of a sequence of holomorphic functions in Template:Math implies also compact convergence, and so the limit function is also holomorphic. Another consequence of this inequality is that the linear functional that evaluates a function Template:Math at a point of Template:Math is actually continuous on Template:Math. The Riesz representation theorem implies that the evaluation functional can be represented as an element of Template:Math. Thus, for every Template:Math, there is a function Template:Math such that for all Template:Math. The integrand is known as the Bergman kernel of Template:Math. This integral kernel satisfies a reproducing property

A Bergman space is an example of a reproducing kernel Hilbert space, which is a Hilbert space of functions along with a kernel Template:Math that verifies a reproducing property analogous to this one. The Hardy space Template:Math also admits a reproducing kernel, known as the Szegő kernel.[36] Reproducing kernels are common in other areas of mathematics as well. For instance, in harmonic analysis the Poisson kernel is a reproducing kernel for the Hilbert space of square-integrable harmonic functions in the unit ball. That the latter is a Hilbert space at all is a consequence of the mean value theorem for harmonic functions.

Applications

Many of the applications of Hilbert spaces exploit the fact that Hilbert spaces support generalizations of simple geometric concepts like projection and change of basis from their usual finite dimensional setting. In particular, the spectral theory of continuous self-adjoint linear operators on a Hilbert space generalizes the usual spectral decomposition of a matrix, and this often plays a major role in applications of the theory to other areas of mathematics and physics.

Sturm–Liouville theory

In the theory of ordinary differential equations, spectral methods on a suitable Hilbert space are used to study the behavior of eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of differential equations. For example, the Sturm–Liouville problem arises in the study of the harmonics of waves in a violin string or a drum, and is a central problem in ordinary differential equations.[37] The problem is a differential equation of the form for an unknown function Template:Math on an interval Template:Closed-closed, satisfying general homogeneous Robin boundary conditions The functions Template:Math, Template:Math, and Template:Math are given in advance, and the problem is to find the function Template:Math and constants Template:Math for which the equation has a solution. The problem only has solutions for certain values of Template:Math, called eigenvalues of the system, and this is a consequence of the spectral theorem for compact operators applied to the integral operator defined by the Green's function for the system. Furthermore, another consequence of this general result is that the eigenvalues Template:Math of the system can be arranged in an increasing sequence tending to infinity.[38][nb 2]

Partial differential equations

Hilbert spaces form a basic tool in the study of partial differential equations.[30] For many classes of partial differential equations, such as linear elliptic equations, it is possible to consider a generalized solution (known as a weak solution) by enlarging the class of functions. Many weak formulations involve the class of Sobolev functions, which is a Hilbert space. A suitable weak formulation reduces to a geometrical problem, the analytic problem of finding a solution or, often what is more important, showing that a solution exists and is unique for given boundary data. For linear elliptic equations, one geometrical result that ensures unique solvability for a large class of problems is the Lax–Milgram theorem. This strategy forms the rudiment of the Galerkin method (a finite element method) for numerical solution of partial differential equations.[39]

A typical example is the Poisson equation Template:Math with Dirichlet boundary conditions in a bounded domain Template:Math in Template:Math. The weak formulation consists of finding a function Template:Math such that, for all continuously differentiable functions Template:Math in Template:Math vanishing on the boundary:

This can be recast in terms of the Hilbert space Template:Math consisting of functions Template:Math such that Template:Math, along with its weak partial derivatives, are square integrable on Template:Math, and vanish on the boundary. The question then reduces to finding Template:Math in this space such that for all Template:Math in this space

where Template:Math is a continuous bilinear form, and Template:Math is a continuous linear functional, given respectively by

Since the Poisson equation is elliptic, it follows from Poincaré's inequality that the bilinear form Template:Math is coercive. The Lax–Milgram theorem then ensures the existence and uniqueness of solutions of this equation.[40]

Hilbert spaces allow for many elliptic partial differential equations to be formulated in a similar way, and the Lax–Milgram theorem is then a basic tool in their analysis. With suitable modifications, similar techniques can be applied to parabolic partial differential equations and certain hyperbolic partial differential equations.[41]

Ergodic theory

The field of ergodic theory is the study of the long-term behavior of chaotic dynamical systems. The protypical case of a field that ergodic theory applies to is thermodynamics, in which—though the microscopic state of a system is extremely complicated (it is impossible to understand the ensemble of individual collisions between particles of matter)—the average behavior over sufficiently long time intervals is tractable. The laws of thermodynamics are assertions about such average behavior. In particular, one formulation of the zeroth law of thermodynamics asserts that over sufficiently long timescales, the only functionally independent measurement that one can make of a thermodynamic system in equilibrium is its total energy, in the form of temperature.[42]

An ergodic dynamical system is one for which, apart from the energy—measured by the Hamiltonian—there are no other functionally independent conserved quantities on the phase space. More explicitly, suppose that the energy Template:Math is fixed, and let Template:Math be the subset of the phase space consisting of all states of energy Template:Math (an energy surface), and let Template:Math denote the evolution operator on the phase space. The dynamical system is ergodic if every invariant measurable functions on Template:Math is constant almost everywhere.[43] An invariant function Template:Math is one for which for all Template:Math on Template:Math and all time Template:Math. Liouville's theorem implies that there exists a measure Template:Math on the energy surface that is invariant under the time translation. As a result, time translation is a unitary transformation of the Hilbert space Template:Math consisting of square-integrable functions on the energy surface Template:Math with respect to the inner product

The von Neumann mean ergodic theorem[23] states the following:

- If Template:Math is a (strongly continuous) one-parameter semigroup of unitary operators on a Hilbert space Template:Math, and Template:Math is the orthogonal projection onto the space of common fixed points of Template:Math, Template:Math, then

For an ergodic system, the fixed set of the time evolution consists only of the constant functions, so the ergodic theorem implies the following:[44] for any function Template:Math,

That is, the long time average of an observable Template:Math is equal to its expectation value over an energy surface.

Fourier analysis

One of the basic goals of Fourier analysis is to decompose a function into a (possibly infinite) linear combination of given basis functions: the associated Fourier series. The classical Fourier series associated to a function Template:Math defined on the interval Template:Math is a series of the form where

The example of adding up the first few terms in a Fourier series for a sawtooth function is shown in the figure. The basis functions are sine waves with wavelengths Template:Math (for integer Template:Math) shorter than the wavelength Template:Math of the sawtooth itself (except for Template:Math, the fundamental wave).

A significant problem in classical Fourier series asks in what sense the Fourier series converges, if at all, to the function Template:Math. Hilbert space methods provide one possible answer to this question.[45] The functions Template:Math form an orthogonal basis of the Hilbert space Template:Math. Consequently, any square-integrable function can be expressed as a series and, moreover, this series converges in the Hilbert space sense (that is, in the [[mean convergence|Template:Math mean]]).

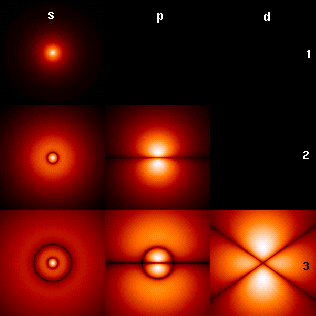

The problem can also be studied from the abstract point of view: every Hilbert space has an orthonormal basis, and every element of the Hilbert space can be written in a unique way as a sum of multiples of these basis elements. The coefficients appearing on these basis elements are sometimes known abstractly as the Fourier coefficients of the element of the space.[46] The abstraction is especially useful when it is more natural to use different basis functions for a space such as Template:Math. In many circumstances, it is desirable not to decompose a function into trigonometric functions, but rather into orthogonal polynomials or wavelets for instance,[47] and in higher dimensions into spherical harmonics.[48]

For instance, if Template:Math are any orthonormal basis functions of Template:Math, then a given function in Template:Math can be approximated as a finite linear combination[49]

The coefficients Template:Math are selected to make the magnitude of the difference Template:Math as small as possible. Geometrically, the best approximation is the orthogonal projection of Template:Math onto the subspace consisting of all linear combinations of the Template:Math, and can be calculated by[50]

That this formula minimizes the difference Template:Math is a consequence of Bessel's inequality and Parseval's formula.

In various applications to physical problems, a function can be decomposed into physically meaningful eigenfunctions of a differential operator (typically the Laplace operator): this forms the foundation for the spectral study of functions, in reference to the spectrum of the differential operator.[51] A concrete physical application involves the problem of hearing the shape of a drum: given the fundamental modes of vibration that a drumhead is capable of producing, can one infer the shape of the drum itself?[52] The mathematical formulation of this question involves the Dirichlet eigenvalues of the Laplace equation in the plane, that represent the fundamental modes of vibration in direct analogy with the integers that represent the fundamental modes of vibration of the violin string.

Spectral theory also underlies certain aspects of the Fourier transform of a function. Whereas Fourier analysis decomposes a function defined on a compact set into the discrete spectrum of the Laplacian (which corresponds to the vibrations of a violin string or drum), the Fourier transform of a function is the decomposition of a function defined on all of Euclidean space into its components in the continuous spectrum of the Laplacian. The Fourier transformation is also geometrical, in a sense made precise by the Plancherel theorem, that asserts that it is an isometry of one Hilbert space (the "time domain") with another (the "frequency domain"). This isometry property of the Fourier transformation is a recurring theme in abstract harmonic analysis (since it reflects the conservation of energy for the continuous Fourier Transform), as evidenced for instance by the Plancherel theorem for spherical functions occurring in noncommutative harmonic analysis.

Quantum mechanics

Template:Main In the mathematically rigorous formulation of quantum mechanics, developed by John von Neumann,[53] the possible states (more precisely, the pure states) of a quantum mechanical system are represented by unit vectors (called state vectors) residing in a complex separable Hilbert space, known as the state space, well defined up to a complex number of norm 1 (the phase factor). In other words, the possible states are points in the projectivization of a Hilbert space, usually called the complex projective space. The exact nature of this Hilbert space is dependent on the system; for example, the position and momentum states for a single non-relativistic spin zero particle is the space of all square-integrable functions, while the states for the spin of a single proton are unit elements of the two-dimensional complex Hilbert space of spinors. Each observable is represented by a self-adjoint linear operator acting on the state space. Each eigenstate of an observable corresponds to an eigenvector of the operator, and the associated eigenvalue corresponds to the value of the observable in that eigenstate.[54]

The inner product between two state vectors is a complex number known as a probability amplitude. During an ideal measurement of a quantum mechanical system, the probability that a system collapses from a given initial state to a particular eigenstate is given by the square of the absolute value of the probability amplitudes between the initial and final states.[55] The possible results of a measurement are the eigenvalues of the operator—which explains the choice of self-adjoint operators, for all the eigenvalues must be real. The probability distribution of an observable in a given state can be found by computing the spectral decomposition of the corresponding operator.[56]

For a general system, states are typically not pure, but instead are represented as statistical mixtures of pure states, or mixed states, given by density matrices: self-adjoint operators of trace one on a Hilbert space.[57] Moreover, for general quantum mechanical systems, the effects of a single measurement can influence other parts of a system in a manner that is described instead by a positive operator valued measure. Thus the structure both of the states and observables in the general theory is considerably more complicated than the idealization for pure states.[58]

Probability theory

In probability theory, Hilbert spaces also have diverse applications. Here a fundamental Hilbert space is the space of random variables on a given probability space, having class (finite first and second moments). A common operation in statistics is that of centering a random variable by subtracting its expectation. Thus if is a random variable, then is its centering. In the Hilbert space view, this is the orthogonal projection of onto the kernel of the expectation operator, which a continuous linear functional on the Hilbert space (in fact, the inner product with the constant random variable 1), and so this kernel is a closed subspace.

The conditional expectation has a natural interpretation in the Hilbert space.[59] Suppose that a probability space is given, where is a sigma algebra on the set , and is a probability measure on the measure space . If is a sigma subalgebra of , then the conditional expectation is the orthogonal projection of onto the subspace of consisting of the -measurable functions. If the random variable in is independent of the sigma algebra then conditional expectation , i.e., its projection onto the -measurable functions is constant. Equivalently, the projection of its centering is zero.

In particular, if two random variables and (in ) are independent, then the centered random variables and are orthogonal. (This means that the two variables have zero covariance: they are uncorrelated.) In that case, the Pythagorean theorem in the kernel of the expectation operator implies that the variances of and satisfy the identity: sometimes called the Pythagorean theorem of statistics, and is of importance in linear regression.[60] As Template:Harvtxt puts it, "the analysis of variance may be viewed as the decomposition of the squared length of a vector into the sum of the squared lengths of several vectors, using the Pythagorean Theorem."

The theory of martingales can be formulated in Hilbert spaces. A martingale in a Hilbert space is a sequence of elements of a Hilbert space such that, for each Template:Math, is the orthogonal projection of onto the linear hull of .[61] If the are random variables, this reproduces the usual definition of a (discrete) martingale: the expectation of , conditioned on , is equal to .

Hilbert spaces are also used throughout the foundations of the Itô calculus.[62] To any square-integrable martingale, it is possible to associate a Hilbert norm on the space of equivalence classes of progressively measurable processes with respect to the martingale (using the quadratic variation of the martingale as the measure). The Itô integral can be constructed by first defining it for simple processes, and then exploiting their density in the Hilbert space. A noteworthy result is then the Itô isometry, which attests that for any martingale M having quadratic variation measure , and any progressively measurable process H: whenever the expectation on the right-hand side is finite.

A deeper application of Hilbert spaces that is especially important in the theory of Gaussian processes is an attempt, due to Leonard Gross and others, to make sense of certain formal integrals over infinite dimensional spaces like the Feynman path integral from quantum field theory. The problem with integral like this is that there is no infinite dimensional Lebesgue measure. The notion of an abstract Wiener space allows one to construct a measure on a Banach space Template:Math that contains a Hilbert space Template:Math, called the Cameron–Martin space, as a dense subset, out of a finitely additive cylinder set measure on Template:Math. The resulting measure on Template:Math is countably additive and invariant under translation by elements of Template:Math, and this provides a mathematically rigorous way of thinking of the Wiener measure as a Gaussian measure on the Sobolev space .[63]

Color perception

Template:Main Any true physical color can be represented by a combination of pure spectral colors. As physical colors can be composed of any number of spectral colors, the space of physical colors may aptly be represented by a Hilbert space over spectral colors. Humans have three types of cone cells for color perception, so the perceivable colors can be represented by 3-dimensional Euclidean space. The many-to-one linear mapping from the Hilbert space of physical colors to the Euclidean space of human perceivable colors explains why many distinct physical colors may be perceived by humans to be identical (e.g., pure yellow light versus a mix of red and green light, see Metamerism).[64][65]

Properties

Pythagorean identity

Two vectors Template:Math and Template:Math in a Hilbert space Template:Math are orthogonal when Template:Math. The notation for this is Template:Math. More generally, when Template:Math is a subset in Template:Math, the notation Template:Math means that Template:Math is orthogonal to every element from Template:Math.

When Template:Math and Template:Math are orthogonal, one has

By induction on Template:Math, this is extended to any family Template:Math of Template:Math orthogonal vectors,

Whereas the Pythagorean identity as stated is valid in any inner product space, completeness is required for the extension of the Pythagorean identity to series.[66] A series Template:Math of orthogonal vectors converges in Template:Math if and only if the series of squares of norms converges, and Furthermore, the sum of a series of orthogonal vectors is independent of the order in which it is taken.

Parallelogram identity and polarization

By definition, every Hilbert space is also a Banach space. Furthermore, in every Hilbert space the following parallelogram identity holds:[67]

Conversely, every Banach space in which the parallelogram identity holds is a Hilbert space, and the inner product is uniquely determined by the norm by the polarization identity.[68] For real Hilbert spaces, the polarization identity is

For complex Hilbert spaces, it is

The parallelogram law implies that any Hilbert space is a uniformly convex Banach space.[69]

Best approximation

This subsection employs the Hilbert projection theorem. If Template:Math is a non-empty closed convex subset of a Hilbert space Template:Math and Template:Math a point in Template:Math, there exists a unique point Template:Math that minimizes the distance between Template:Math and points in Template:Math,[70]

This is equivalent to saying that there is a point with minimal norm in the translated convex set Template:Math. The proof consists in showing that every minimizing sequence Template:Math is Cauchy (using the parallelogram identity) hence converges (using completeness) to a point in Template:Math that has minimal norm. More generally, this holds in any uniformly convex Banach space.[71]

When this result is applied to a closed subspace Template:Math of Template:Math, it can be shown that the point Template:Math closest to Template:Math is characterized by[72]

This point Template:Math is the orthogonal projection of Template:Math onto Template:Math, and the mapping Template:Math is linear (see Template:Slink). This result is especially significant in applied mathematics, especially numerical analysis, where it forms the basis of least squares methods.[73]

In particular, when Template:Math is not equal to Template:Math, one can find a nonzero vector Template:Math orthogonal to Template:Math (select Template:Math and Template:Math). A very useful criterion is obtained by applying this observation to the closed subspace Template:Math generated by a subset Template:Math of Template:Math.

- A subset Template:Math of Template:Math spans a dense vector subspace if (and only if) the vector 0 is the sole vector Template:Math orthogonal to Template:Math.

Duality

The dual space Template:Math is the space of all continuous linear functions from the space Template:Math into the base field. It carries a natural norm, defined by This norm satisfies the parallelogram law, and so the dual space is also an inner product space where this inner product can be defined in terms of this dual norm by using the polarization identity. The dual space is also complete so it is a Hilbert space in its own right. If Template:Math is a complete orthonormal basis for Template:Mvar then the inner product on the dual space of any two is where all but countably many of the terms in this series are zero.

The Riesz representation theorem affords a convenient description of the dual space. To every element Template:Math of Template:Math, there is a unique element Template:Math of Template:Math, defined by where moreover,

The Riesz representation theorem states that the map from Template:Math to Template:Math defined by Template:Math is surjective, which makes this map an isometric antilinear isomorphism.[74] So to every element Template:Math of the dual Template:Math there exists one and only one Template:Math in Template:Math such that for all Template:Math. The inner product on the dual space Template:Math satisfies

The reversal of order on the right-hand side restores linearity in Template:Math from the antilinearity of Template:Math. In the real case, the antilinear isomorphism from Template:Math to its dual is actually an isomorphism, and so real Hilbert spaces are naturally isomorphic to their own duals.

The representing vector Template:Math is obtained in the following way. When Template:Math, the kernel Template:Math is a closed vector subspace of Template:Math, not equal to Template:Math, hence there exists a nonzero vector Template:Math orthogonal to Template:Math. The vector Template:Math is a suitable scalar multiple Template:Math of Template:Math. The requirement that Template:Math yields

This correspondence Template:Math is exploited by the bra–ket notation popular in physics.[75] It is common in physics to assume that the inner product, denoted by Template:Math, is linear on the right, The result Template:Math can be seen as the action of the linear functional Template:Math (the bra) on the vector Template:Math (the ket).

The Riesz representation theorem relies fundamentally not just on the presence of an inner product, but also on the completeness of the space. In fact, the theorem implies that the topological dual of any inner product space can be identified with its completion.[76] An immediate consequence of the Riesz representation theorem is also that a Hilbert space Template:Math is reflexive, meaning that the natural map from Template:Math into its double dual space is an isomorphism.

Weakly convergent sequences

Template:Main In a Hilbert space Template:Math, a sequence Template:Math is weakly convergent to a vector Template:Math when for every Template:Math.

For example, any orthonormal sequence Template:Math converges weakly to 0, as a consequence of Bessel's inequality. Every weakly convergent sequence Template:Math is bounded, by the uniform boundedness principle.

Conversely, every bounded sequence in a Hilbert space admits weakly convergent subsequences (Alaoglu's theorem).[77] This fact may be used to prove minimization results for continuous convex functionals, in the same way that the Bolzano–Weierstrass theorem is used for continuous functions on Template:Math. Among several variants, one simple statement is as follows:[78]

- If Template:Math is a convex continuous function such that Template:Math tends to Template:Math when Template:Math tends to Template:Math, then Template:Math admits a minimum at some point Template:Math.

This fact (and its various generalizations) are fundamental for direct methods in the calculus of variations. Minimization results for convex functionals are also a direct consequence of the slightly more abstract fact that closed bounded convex subsets in a Hilbert space Template:Math are weakly compact, since Template:Math is reflexive. The existence of weakly convergent subsequences is a special case of the Eberlein–Šmulian theorem.

Banach space properties

Any general property of Banach spaces continues to hold for Hilbert spaces. The open mapping theorem states that a continuous surjective linear transformation from one Banach space to another is an open mapping meaning that it sends open sets to open sets. A corollary is the bounded inverse theorem, that a continuous and bijective linear function from one Banach space to another is an isomorphism (that is, a continuous linear map whose inverse is also continuous). This theorem is considerably simpler to prove in the case of Hilbert spaces than in general Banach spaces.[79] The open mapping theorem is equivalent to the closed graph theorem, which asserts that a linear function from one Banach space to another is continuous if and only if its graph is a closed set.[80] In the case of Hilbert spaces, this is basic in the study of unbounded operators (see Closed operator).

The (geometrical) Hahn–Banach theorem asserts that a closed convex set can be separated from any point outside it by means of a hyperplane of the Hilbert space. This is an immediate consequence of the best approximation property: if Template:Math is the element of a closed convex set Template:Math closest to Template:Math, then the separating hyperplane is the plane perpendicular to the segment Template:Math passing through its midpoint.[81]

Operators on Hilbert spaces

Bounded operators

The continuous linear operators Template:Math from a Hilbert space Template:Math to a second Hilbert space Template:Math are bounded in the sense that they map bounded sets to bounded sets.[82] Conversely, if an operator is bounded, then it is continuous. The space of such bounded linear operators has a norm, the operator norm given by

The sum and the composite of two bounded linear operators is again bounded and linear. For y in H2, the map that sends Template:Math to Template:Math is linear and continuous, and according to the Riesz representation theorem can therefore be represented in the form for some vector Template:Math in Template:Math. This defines another bounded linear operator Template:Math, the adjoint of Template:Mvar. The adjoint satisfies Template:Math. When the Riesz representation theorem is used to identify each Hilbert space with its continuous dual space, the adjoint of Template:Mvar can be shown to be identical to the transpose Template:Math of Template:Mvar, which by definition sends to the functional

The set Template:Math of all bounded linear operators on Template:Math (meaning operators Template:Math), together with the addition and composition operations, the norm and the adjoint operation, is a C*-algebra, which is a type of operator algebra.

An element Template:Math of Template:Math is called 'self-adjoint' or 'Hermitian' if Template:Math. If Template:Math is Hermitian and Template:Math for every Template:Math, then Template:Math is called 'nonnegative', written Template:Math; if equality holds only when Template:Math, then Template:Math is called 'positive'. The set of self adjoint operators admits a partial order, in which Template:Math if Template:Math. If Template:Math has the form Template:Math for some Template:Math, then Template:Math is nonnegative; if Template:Math is invertible, then Template:Math is positive. A converse is also true in the sense that, for a non-negative operator Template:Math, there exists a unique non-negative square root Template:Math such that

In a sense made precise by the spectral theorem, self-adjoint operators can usefully be thought of as operators that are "real". An element Template:Math of Template:Math is called normal if Template:Math. Normal operators decompose into the sum of a self-adjoint operator and an imaginary multiple of a self adjoint operator that commute with each other. Normal operators can also usefully be thought of in terms of their real and imaginary parts.

An element Template:Math of Template:Math is called unitary if Template:Math is invertible and its inverse is given by Template:Math. This can also be expressed by requiring that Template:Math be onto and Template:Math for all Template:Math. The unitary operators form a group under composition, which is the isometry group of Template:Math.

An element of Template:Math is compact if it sends bounded sets to relatively compact sets. Equivalently, a bounded operator Template:Math is compact if, for any bounded sequence Template:Math, the sequence Template:Math has a convergent subsequence. Many integral operators are compact, and in fact define a special class of operators known as Hilbert–Schmidt operators that are especially important in the study of integral equations. Fredholm operators differ from a compact operator by a multiple of the identity, and are equivalently characterized as operators with a finite dimensional kernel and cokernel. The index of a Fredholm operator Template:Math is defined by

The index is homotopy invariant, and plays a deep role in differential geometry via the Atiyah–Singer index theorem.

Unbounded operators

Unbounded operators are also tractable in Hilbert spaces, and have important applications to quantum mechanics.[83] An unbounded operator Template:Math on a Hilbert space Template:Math is defined as a linear operator whose domain Template:Math is a linear subspace of Template:Math. Often the domain Template:Math is a dense subspace of Template:Math, in which case Template:Math is known as a densely defined operator.

The adjoint of a densely defined unbounded operator is defined in essentially the same manner as for bounded operators. Self-adjoint unbounded operators play the role of the observables in the mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics. Examples of self-adjoint unbounded operators on the Hilbert space Template:Math are:[84]

- A suitable extension of the differential operator where Template:Math is the imaginary unit and Template:Math is a differentiable function of compact support.

- The multiplication-by-Template:Math operator:

These correspond to the momentum and position observables, respectively. Neither Template:Math nor Template:Math is defined on all of Template:Math, since in the case of Template:Math the derivative need not exist, and in the case of Template:Math the product function need not be square integrable. In both cases, the set of possible arguments form dense subspaces of Template:Math.

Constructions

Direct sums

Two Hilbert spaces Template:Math and Template:Math can be combined into another Hilbert space, called the (orthogonal) direct sum,[85] and denoted

consisting of the set of all ordered pairs Template:Math where Template:Math, Template:Math, and inner product defined by

More generally, if Template:Math is a family of Hilbert spaces indexed by Template:Nowrap, then the direct sum of the Template:Math, denoted consists of the set of all indexed families in the Cartesian product of the Template:Math such that

The inner product is defined by

Each of the Template:Math is included as a closed subspace in the direct sum of all of the Template:Math. Moreover, the Template:Math are pairwise orthogonal. Conversely, if there is a system of closed subspaces, Template:Math, Template:Math, in a Hilbert space Template:Math, that are pairwise orthogonal and whose union is dense in Template:Math, then Template:Math is canonically isomorphic to the direct sum of Template:Math. In this case, Template:Math is called the internal direct sum of the Template:Math. A direct sum (internal or external) is also equipped with a family of orthogonal projections Template:Math onto the Template:Mathth direct summand Template:Math. These projections are bounded, self-adjoint, idempotent operators that satisfy the orthogonality condition

The spectral theorem for compact self-adjoint operators on a Hilbert space Template:Math states that Template:Math splits into an orthogonal direct sum of the eigenspaces of an operator, and also gives an explicit decomposition of the operator as a sum of projections onto the eigenspaces. The direct sum of Hilbert spaces also appears in quantum mechanics as the Fock space of a system containing a variable number of particles, where each Hilbert space in the direct sum corresponds to an additional degree of freedom for the quantum mechanical system. In representation theory, the Peter–Weyl theorem guarantees that any unitary representation of a compact group on a Hilbert space splits as the direct sum of finite-dimensional representations.

Tensor products

Template:Main If Template:Math and Template:Math, then one defines an inner product on the (ordinary) tensor product as follows. On simple tensors, let

This formula then extends by sesquilinearity to an inner product on Template:Math. The Hilbertian tensor product of Template:Math and Template:Math, sometimes denoted by Template:Math, is the Hilbert space obtained by completing Template:Math for the metric associated to this inner product.[86]

An example is provided by the Hilbert space Template:Math. The Hilbertian tensor product of two copies of Template:Math is isometrically and linearly isomorphic to the space Template:Math of square-integrable functions on the square Template:Math. This isomorphism sends a simple tensor Template:Math to the function on the square.

This example is typical in the following sense.[87] Associated to every simple tensor product Template:Math is the rank one operator from Template:Math to Template:Math that maps a given Template:Math as

This mapping defined on simple tensors extends to a linear identification between Template:Math and the space of finite rank operators from Template:Math to Template:Math. This extends to a linear isometry of the Hilbertian tensor product Template:Math with the Hilbert space Template:Math of Hilbert–Schmidt operators from Template:Math to Template:Math.

Orthonormal bases

The notion of an orthonormal basis from linear algebra generalizes over to the case of Hilbert spaces.[88] In a Hilbert space Template:Math, an orthonormal basis is a family Template:Math of elements of Template:Math satisfying the conditions:

- Orthogonality: Every two different elements of Template:Math are orthogonal: Template:Math for all Template:Math with Template:Nowrap.

- Normalization: Every element of the family has norm 1: Template:Math for all Template:Math.

- Completeness: The linear span of the family Template:Math, Template:Math, is dense in H.

A system of vectors satisfying the first two conditions basis is called an orthonormal system or an orthonormal set (or an orthonormal sequence if Template:Math is countable). Such a system is always linearly independent.

Despite the name, an orthonormal basis is not, in general, a basis in the sense of linear algebra (Hamel basis). More precisely, an orthonormal basis is a Hamel basis if and only if the Hilbert space is a finite-dimensional vector space.[89]

Completeness of an orthonormal system of vectors of a Hilbert space can be equivalently restated as:

- for every Template:Math, if Template:Math for all Template:Math, then Template:Math.

This is related to the fact that the only vector orthogonal to a dense linear subspace is the zero vector, for if Template:Math is any orthonormal set and Template:Math is orthogonal to Template:Math, then Template:Math is orthogonal to the closure of the linear span of Template:Math, which is the whole space.

Examples of orthonormal bases include:

- the set Template:Math forms an orthonormal basis of Template:Math with the dot product;

- the sequence Template:Math with Template:Math forms an orthonormal basis of the complex space Template:Math;

In the infinite-dimensional case, an orthonormal basis will not be a basis in the sense of linear algebra; to distinguish the two, the latter basis is also called a Hamel basis. That the span of the basis vectors is dense implies that every vector in the space can be written as the sum of an infinite series, and the orthogonality implies that this decomposition is unique.

Sequence spaces

The space of square-summable sequences of complex numbers is the set of infinite sequences[8] of real or complex numbers such that

This space has an orthonormal basis:

This space is the infinite-dimensional generalization of the space of finite-dimensional vectors. It is usually the first example used to show that in infinite-dimensional spaces, a set that is closed and bounded is not necessarily (sequentially) compact (as is the case in all finite dimensional spaces). Indeed, the set of orthonormal vectors above shows this: It is an infinite sequence of vectors in the unit ball (i.e., the ball of points with norm less than or equal one). This set is clearly bounded and closed; yet, no subsequence of these vectors converges to anything and consequently the unit ball in is not compact. Intuitively, this is because "there is always another coordinate direction" into which the next elements of the sequence can evade.

One can generalize the space in many ways. For example, if Template:Math is any set, then one can form a Hilbert space of sequences with index set Template:Math, defined by[90]

The summation over B is here defined by the supremum being taken over all finite subsets of Template:Math. It follows that, for this sum to be finite, every element of Template:Math has only countably many nonzero terms. This space becomes a Hilbert space with the inner product

for all Template:Math. Here the sum also has only countably many nonzero terms, and is unconditionally convergent by the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.

An orthonormal basis of Template:Math is indexed by the set Template:Math, given by

Template:Anchor Template:Anchor

Bessel's inequality and Parseval's formula

Let Template:Math be a finite orthonormal system in Template:Math. For an arbitrary vector Template:Math, let

Then Template:Math for every Template:Math. It follows that Template:Math is orthogonal to each Template:Math, hence Template:Math is orthogonal to Template:Math. Using the Pythagorean identity twice, it follows that

Let Template:Math, be an arbitrary orthonormal system in Template:Math. Applying the preceding inequality to every finite subset Template:Math of Template:Math gives Bessel's inequality:[91] (according to the definition of the sum of an arbitrary family of non-negative real numbers).

Geometrically, Bessel's inequality implies that the orthogonal projection of Template:Math onto the linear subspace spanned by the Template:Math has norm that does not exceed that of Template:Math. In two dimensions, this is the assertion that the length of the leg of a right triangle may not exceed the length of the hypotenuse.

Bessel's inequality is a stepping stone to the stronger result called Parseval's identity, which governs the case when Bessel's inequality is actually an equality. By definition, if Template:Math is an orthonormal basis of Template:Math, then every element Template:Math of Template:Math may be written as

Even if Template:Math is uncountable, Bessel's inequality guarantees that the expression is well-defined and consists only of countably many nonzero terms. This sum is called the Fourier expansion of Template:Math, and the individual coefficients Template:Math are the Fourier coefficients of Template:Math. Parseval's identity then asserts that[92]

Conversely,[92] if Template:Math is an orthonormal set such that Parseval's identity holds for every Template:Math, then Template:Math is an orthonormal basis.

Hilbert dimension

As a consequence of Zorn's lemma, every Hilbert space admits an orthonormal basis; furthermore, any two orthonormal bases of the same space have the same cardinality, called the Hilbert dimension of the space.[93] For instance, since Template:Math has an orthonormal basis indexed by Template:Math, its Hilbert dimension is the cardinality of Template:Math (which may be a finite integer, or a countable or uncountable cardinal number).

The Hilbert dimension is not greater than the Hamel dimension (the usual dimension of a vector space).

As a consequence of Parseval's identity,[94] if Template:Math is an orthonormal basis of Template:Math, then the map Template:Math defined by Template:Math is an isometric isomorphism of Hilbert spaces: it is a bijective linear mapping such that for all Template:Math. The cardinal number of Template:Math is the Hilbert dimension of Template:Math. Thus every Hilbert space is isometrically isomorphic to a sequence space Template:Math for some set Template:Math.

Separable spaces

By definition, a Hilbert space is separable provided it contains a dense countable subset. Along with Zorn's lemma, this means a Hilbert space is separable if and only if it admits a countable orthonormal basis. All infinite-dimensional separable Hilbert spaces are therefore isometrically isomorphic to the square-summable sequence space

In the past, Hilbert spaces were often required to be separable as part of the definition.[95]

In quantum field theory

Most spaces used in physics are separable, and since these are all isomorphic to each other, one often refers to any infinite-dimensional separable Hilbert space as "the Hilbert space" or just "Hilbert space".[96] Even in quantum field theory, most of the Hilbert spaces are in fact separable, as stipulated by the Wightman axioms. However, it is sometimes argued that non-separable Hilbert spaces are also important in quantum field theory, roughly because the systems in the theory possess an infinite number of degrees of freedom and any infinite Hilbert tensor product (of spaces of dimension greater than one) is non-separable.[97] For instance, a bosonic field can be naturally thought of as an element of a tensor product whose factors represent harmonic oscillators at each point of space. From this perspective, the natural state space of a boson might seem to be a non-separable space.[97] However, it is only a small separable subspace of the full tensor product that can contain physically meaningful fields (on which the observables can be defined). Another non-separable Hilbert space models the state of an infinite collection of particles in an unbounded region of space. An orthonormal basis of the space is indexed by the density of the particles, a continuous parameter, and since the set of possible densities is uncountable, the basis is not countable.[97]

Orthogonal complements and projections

If Template:Math is a subset of a Hilbert space Template:Math, the set of vectors orthogonal to Template:Math is defined by

The set Template:Math is a closed subspace of Template:Math (can be proved easily using the linearity and continuity of the inner product) and so forms itself a Hilbert space. If Template:Math is a closed subspace of Template:Math, then Template:Math is called the Template:Em of Template:Math. In fact, every Template:Math can then be written uniquely as Template:Math, with Template:Math and Template:Math. Therefore, Template:Math is the internal Hilbert direct sum of Template:Math and Template:Math.

The linear operator Template:Math that maps Template:Math to Template:Math is called the Template:Em onto Template:Math. There is a natural one-to-one correspondence between the set of all closed subspaces of Template:Math and the set of all bounded self-adjoint operators Template:Math such that Template:Math. Specifically,

This provides the geometrical interpretation of Template:Math: it is the best approximation to x by elements of V.[98]

Projections Template:Math and Template:Math are called mutually orthogonal if Template:Math. This is equivalent to Template:Math and Template:Math being orthogonal as subspaces of Template:Math. The sum of the two projections Template:Math and Template:Math is a projection only if Template:Math and Template:Math are orthogonal to each other, and in that case Template:Math.[99] The composite Template:Math is generally not a projection; in fact, the composite is a projection if and only if the two projections commute, and in that case Template:Math.[100]

By restricting the codomain to the Hilbert space Template:Math, the orthogonal projection Template:Math gives rise to a projection mapping Template:Math; it is the adjoint of the inclusion mapping meaning that for all Template:Math and Template:Math.

The operator norm of the orthogonal projection Template:Math onto a nonzero closed subspace Template:Math is equal to 1:

Every closed subspace V of a Hilbert space is therefore the image of an operator Template:Math of norm one such that Template:Math. The property of possessing appropriate projection operators characterizes Hilbert spaces:[101]

- A Banach space of dimension higher than 2 is (isometrically) a Hilbert space if and only if, for every closed subspace Template:Math, there is an operator Template:Math of norm one whose image is Template:Math such that Template:Math.

While this result characterizes the metric structure of a Hilbert space, the structure of a Hilbert space as a topological vector space can itself be characterized in terms of the presence of complementary subspaces:[102]

- A Banach space Template:Math is topologically and linearly isomorphic to a Hilbert space if and only if, to every closed subspace Template:Math, there is a closed subspace Template:Math such that Template:Math is equal to the internal direct sum Template:Math.

The orthogonal complement satisfies some more elementary results. It is a monotone function in the sense that if Template:Math, then Template:Math with equality holding if and only if Template:Math is contained in the closure of Template:Math. This result is a special case of the Hahn–Banach theorem. The closure of a subspace can be completely characterized in terms of the orthogonal complement: if Template:Math is a subspace of Template:Math, then the closure of Template:Math is equal to Template:Math. The orthogonal complement is thus a Galois connection on the partial order of subspaces of a Hilbert space. In general, the orthogonal complement of a sum of subspaces is the intersection of the orthogonal complements:[103]

If the Template:Math are in addition closed, then

Spectral theory

There is a well-developed spectral theory for self-adjoint operators in a Hilbert space, that is roughly analogous to the study of symmetric matrices over the reals or self-adjoint matrices over the complex numbers.[104] In the same sense, one can obtain a "diagonalization" of a self-adjoint operator as a suitable sum (actually an integral) of orthogonal projection operators.

The spectrum of an operator Template:Math, denoted Template:Math, is the set of complex numbers Template:Math such that Template:Math lacks a continuous inverse. If Template:Math is bounded, then the spectrum is always a compact set in the complex plane, and lies inside the disc Template:Math. If Template:Math is self-adjoint, then the spectrum is real. In fact, it is contained in the interval Template:Math where

Moreover, Template:Math and Template:Math are both actually contained within the spectrum.

The eigenspaces of an operator Template:Math are given by

Unlike with finite matrices, not every element of the spectrum of Template:Math must be an eigenvalue: the linear operator Template:Math may only lack an inverse because it is not surjective. Elements of the spectrum of an operator in the general sense are known as spectral values. Since spectral values need not be eigenvalues, the spectral decomposition is often more subtle than in finite dimensions.

However, the spectral theorem of a self-adjoint operator Template:Math takes a particularly simple form if, in addition, Template:Math is assumed to be a compact operator. The spectral theorem for compact self-adjoint operators states:[105]

- A compact self-adjoint operator Template:Math has only countably (or finitely) many spectral values. The spectrum of Template:Math has no limit point in the complex plane except possibly zero. The eigenspaces of Template:Math decompose Template:Math into an orthogonal direct sum: Moreover, if Template:Math denotes the orthogonal projection onto the eigenspace Template:Math, then where the sum converges with respect to the norm on Template:Math.

This theorem plays a fundamental role in the theory of integral equations, as many integral operators are compact, in particular those that arise from Hilbert–Schmidt operators.

The general spectral theorem for self-adjoint operators involves a kind of operator-valued Riemann–Stieltjes integral, rather than an infinite summation.[106] The spectral family associated to Template:Math associates to each real number λ an operator Template:Math, which is the projection onto the nullspace of the operator Template:Math, where the positive part of a self-adjoint operator is defined by

The operators Template:Math are monotone increasing relative to the partial order defined on self-adjoint operators; the eigenvalues correspond precisely to the jump discontinuities. One has the spectral theorem, which asserts

The integral is understood as a Riemann–Stieltjes integral, convergent with respect to the norm on Template:Math. In particular, one has the ordinary scalar-valued integral representation

A somewhat similar spectral decomposition holds for normal operators, although because the spectrum may now contain non-real complex numbers, the operator-valued Stieltjes measure Template:Math must instead be replaced by a resolution of the identity.

A major application of spectral methods is the spectral mapping theorem, which allows one to apply to a self-adjoint operator Template:Math any continuous complex function Template:Math defined on the spectrum of Template:Math by forming the integral

The resulting continuous functional calculus has applications in particular to pseudodifferential operators.[107]

The spectral theory of unbounded self-adjoint operators is only marginally more difficult than for bounded operators. The spectrum of an unbounded operator is defined in precisely the same way as for bounded operators: Template:Math is a spectral value if the resolvent operator

fails to be a well-defined continuous operator. The self-adjointness of Template:Math still guarantees that the spectrum is real. Thus the essential idea of working with unbounded operators is to look instead at the resolvent Template:Math where Template:Math is nonreal. This is a bounded normal operator, which admits a spectral representation that can then be transferred to a spectral representation of Template:Math itself. A similar strategy is used, for instance, to study the spectrum of the Laplace operator: rather than address the operator directly, one instead looks as an associated resolvent such as a Riesz potential or Bessel potential.

A precise version of the spectral theorem in this case is:[108] Template:Math theorem There is also a version of the spectral theorem that applies to unbounded normal operators.

In popular culture

In Gravity's Rainbow (1973), a novel by Thomas Pynchon, one of the characters is called "Sammy Hilbert-Spaess", a pun on "Hilbert Space". The novel refers also to Gödel's incompleteness theorems.[109]

See also

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

Remarks

Notes

References

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Springer.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:MacTutor

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation

- Template:Rudin Walter Functional Analysis

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation; originally published Monografje Matematyczne, vol. 7, Warszawa, 1937.

- Template:Schaefer Wolff Topological Vector Spaces

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Cite book.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

External links

Template:Wikibooks Template:Commons category

Template:Hilbert space Template:Navbox Template:Functional analysis Template:Navbox Template:Authority control

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ However, some sources call finite-dimensional spaces with these properties pre-Hilbert spaces, reserving the term "Hilbert space" for infinite-dimensional spaces; see, e.g., Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ The mathematical material in this section can be found in any good textbook on functional analysis, such as Template:Harvtxt, Template:Harvtxt, Template:Harvtxt or Template:Harvtxt.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Largely from the work of Hermann Grassmann, at the urging of August Ferdinand Möbius Template:Harv. The first modern axiomatic account of abstract vector spaces ultimately appeared in Giuseppe Peano's 1888 account (Template:Harvnb; Template:Harvnb).

- ↑ A detailed account of the history of Hilbert spaces can be found in Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb. Further details on the history of integration theory can be found in Template:Harvtxt and Template:Harvtxt.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ In Template:Harvtxt, the result that every linear functional on Template:Math is represented by integration is jointly attributed to Template:Harvtxt and Template:Harvtxt. The general result, that the dual of a Hilbert space is identified with the Hilbert space itself, can be found in Template:Harvtxt.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Abramowitz Stegun ref

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb