Riemann–Liouville integral

{{#invoke:sidebar|collapsible | class = plainlist | titlestyle = padding-bottom:0.25em; | pretitle = Part of a series of articles about | title = Calculus | image = | listtitlestyle = text-align:center; | liststyle = border-top:1px solid #aaa;padding-top:0.15em;border-bottom:1px solid #aaa; | expanded = Fractional calculus | abovestyle = padding:0.15em 0.25em 0.3em;font-weight:normal; | above =

Template:EndflatlistTemplate:Startflatlist

| list2name = differential | list2titlestyle = display:block;margin-top:0.65em; | list2title = Template:Bigger | list2 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | heading1 = Definitions | content1 =

| heading2 = Concepts | content2 =

- Differentiation notation

- Second derivative

- Implicit differentiation

- Logarithmic differentiation

- Related rates

- Taylor's theorem

| heading3 = Rules and identities | content3 =

- Sum

- Product

- Chain

- Power

- Quotient

- L'Hôpital's rule

- Inverse

- General Leibniz

- Faà di Bruno's formula

- Reynolds

}}

| list3name = integral | list3title = Template:Bigger | list3 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | content1 =

| heading2 = Definitions

| content2 =

- Antiderivative

- Integral (improper)

- Riemann integral

- Lebesgue integration

- Contour integration

- Integral of inverse functions

| heading3 = Integration by | content3 =

- Parts

- Discs

- Cylindrical shells

- Substitution (trigonometric, tangent half-angle, Euler)

- Euler's formula

- Partial fractions (Heaviside's method)

- Changing order

- Reduction formulae

- Differentiating under the integral sign

- Risch algorithm

}}

| list4name = series | list4title = Template:Bigger | list4 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | content1 =

| heading2 = Convergence tests | content2 =

- Summand limit (term test)

- Ratio

- Root

- Integral

- Direct comparison

Limit comparison- Alternating series

- Cauchy condensation

- Dirichlet

- Abel

}}

| list5name = vector | list5title = Template:Bigger | list5 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | content1 =

| heading2 = Theorems | content2 =

}}

| list6name = multivariable | list6title = Template:Bigger | list6 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | heading1 = Formalisms | content1 =

| heading2 = Definitions | content2 =

- Partial derivative

- Multiple integral

- Line integral

- Surface integral

- Volume integral

- Jacobian

- Hessian

}}

| list7name = advanced | list7title = Template:Bigger | list7 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | content1 =

}}

| list8name = specialized | list8title = Template:Bigger | list8 =

| list9name = miscellanea | list9title = Template:Bigger | list9 =

- Precalculus

- History

- Glossary

- List of topics

- Integration Bee

- Mathematical analysis

- Nonstandard analysis

}}

In mathematics, the Riemann–Liouville integral associates with a real function another function Template:Math of the same kind for each value of the parameter Template:Math. The integral is a manner of generalization of the repeated antiderivative of Template:Mvar in the sense that for positive integer values of Template:Mvar, Template:Math is an iterated antiderivative of Template:Mvar of order Template:Mvar. The Riemann–Liouville integral is named for Bernhard Riemann and Joseph Liouville, the latter of whom was the first to consider the possibility of fractional calculus in 1832.[1][2][3][4] The operator agrees with the Euler transform, after Leonhard Euler, when applied to analytic functions.[5] It was generalized to arbitrary dimensions by Marcel Riesz, who introduced the Riesz potential.

Motivation

The Riemann-Liouville integral is motivated from Cauchy formula for repeated integration. For a function Template:Mvar continuous on the interval [[[:Template:Mvar]],Template:Mvar], the Cauchy formula for Template:Mvar-fold repeated integration states that

Now, this formula can be generalized to any positive real number by replacing positive integer Template:Mvar with Template:Mvar, Therefore we obtain the definition of Riemann-Liouville fractional Integral by

Definition

The Riemann–Liouville integral is defined by

where Template:Math is the gamma function and Template:Mvar is an arbitrary but fixed base point. The integral is well-defined provided Template:Mvar is a locally integrable function, and Template:Mvar is a complex number in the half-plane Template:Math. The dependence on the base-point Template:Mvar is often suppressed, and represents a freedom in constant of integration. Clearly Template:Math is an antiderivative of Template:Mvar (of first order), and for positive integer values of Template:Mvar, Template:Math is an antiderivative of order Template:Mvar by Cauchy formula for repeated integration. Another notation, which emphasizes the base point, is[6]

This also makes sense if Template:Math, with suitable restrictions on Template:Mvar.

The fundamental relations hold

the latter of which is a semigroup property.[1] These properties make possible not only the definition of fractional integration, but also of fractional differentiation, by taking enough derivatives of Template:Math.

Properties

Fix a bounded interval Template:Open-open. The operator Template:Math associates to each integrable function Template:Mvar on Template:Open-open the function Template:Math on Template:Open-open which is also integrable by Fubini's theorem. Thus Template:Math defines a linear operator on [[Lp space|Template:Math]]:

Fubini's theorem also shows that this operator is continuous with respect to the Banach space structure on Template:Mvar1, and that the following inequality holds:

Here Template:Math denotes the norm on Template:Math.

More generally, by Hölder's inequality, it follows that if Template:Math, then Template:Math as well, and the analogous inequality holds

where Template:Math is the [[Lp space|Template:MvarTemplate:Mvar norm]] on the interval Template:Open-open. Thus we have a bounded linear operator Template:Math. Furthermore, Template:Math in the Template:Math sense as Template:Math along the real axis. That is

for all Template:Math. Moreover, by estimating the maximal function of Template:Mvar, one can show that the limit Template:Math holds pointwise almost everywhere.

The operator Template:Math is well-defined on the set of locally integrable function on the whole real line . It defines a bounded transformation on any of the Banach spaces of functions of exponential type consisting of locally integrable functions for which the norm

is finite. For Template:Math, the Laplace transform of Template:Math takes the particularly simple form

for Template:Math. Here Template:Math denotes the Laplace transform of Template:Mvar, and this property expresses that Template:Math is a Fourier multiplier.

Fractional derivatives

One can define fractional-order derivatives of Template:Mvar as well by

where Template:Math denotes the ceiling function. One also obtains a differintegral interpolating between differentiation and integration by defining

An alternative fractional derivative was introduced by Caputo in 1967,[7] and produces a derivative that has different properties: it produces zero from constant functions and, more importantly, the initial value terms of the Laplace Transform are expressed by means of the values of that function and of its derivative of integer order rather than the derivatives of fractional order as in the Riemann–Liouville derivative.[8] The Caputo fractional derivative with base point Template:Mvar, is then:

Another representation is:

Fractional derivative of a basic power function

Let us assume that Template:Math is a monomial of the form

The first derivative is as usual

Repeating this gives the more general result that

which, after replacing the factorials with the gamma function, leads to

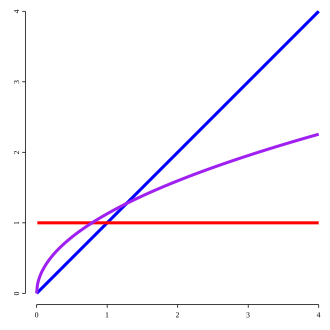

For Template:Math and Template:Math, we obtain the half-derivative of the function as

To demonstrate that this is, in fact, the "half derivative" (where Template:Math), we repeat the process to get:

(because and Template:Math) which is indeed the expected result of

For negative integer power Template:Math, 1/ is 0, so it is convenient to use the following relation:[9]

This extension of the above differential operator need not be constrained only to real powers; it also applies for complex powers. For example, the Template:Math-th derivative of the Template:Math-th derivative yields the second derivative. Also setting negative values for Template:Mvar yields integrals.

For a general function Template:Math and Template:Math, the complete fractional derivative is

For arbitrary Template:Mvar, since the gamma function is infinite for negative (real) integers, it is necessary to apply the fractional derivative after the integer derivative has been performed. For example,

Laplace transform

Template:Unreferenced section We can also come at the question via the Laplace transform. Knowing that

and

and so on, we assert

- .

For example,

as expected. Indeed, given the convolution rule

and shorthanding Template:Math for clarity, we find that

which is what Cauchy gave us above.

Laplace transforms "work" on relatively few functions, but they are often useful for solving fractional differential equations.

See also

Notes

References

- Template:Springer.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Springer.

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.