Fundamental theorem of calculus

Template:Short description {{#invoke:sidebar|collapsible | class = plainlist | titlestyle = padding-bottom:0.25em; | pretitle = Part of a series of articles about | title = Calculus | image = | listtitlestyle = text-align:center; | liststyle = border-top:1px solid #aaa;padding-top:0.15em;border-bottom:1px solid #aaa; | expanded = | abovestyle = padding:0.15em 0.25em 0.3em;font-weight:normal; | above =

Template:EndflatlistTemplate:Startflatlist

| list2name = differential | list2titlestyle = display:block;margin-top:0.65em; | list2title = Template:Bigger | list2 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | heading1 = Definitions | content1 =

| heading2 = Concepts | content2 =

- Differentiation notation

- Second derivative

- Implicit differentiation

- Logarithmic differentiation

- Related rates

- Taylor's theorem

| heading3 = Rules and identities | content3 =

- Sum

- Product

- Chain

- Power

- Quotient

- L'Hôpital's rule

- Inverse

- General Leibniz

- Faà di Bruno's formula

- Reynolds

}}

| list3name = integral | list3title = Template:Bigger | list3 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | content1 =

| heading2 = Definitions

| content2 =

- Antiderivative

- Integral (improper)

- Riemann integral

- Lebesgue integration

- Contour integration

- Integral of inverse functions

| heading3 = Integration by | content3 =

- Parts

- Discs

- Cylindrical shells

- Substitution (trigonometric, tangent half-angle, Euler)

- Euler's formula

- Partial fractions (Heaviside's method)

- Changing order

- Reduction formulae

- Differentiating under the integral sign

- Risch algorithm

}}

| list4name = series | list4title = Template:Bigger | list4 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | content1 =

| heading2 = Convergence tests | content2 =

- Summand limit (term test)

- Ratio

- Root

- Integral

- Direct comparison

Limit comparison- Alternating series

- Cauchy condensation

- Dirichlet

- Abel

}}

| list5name = vector | list5title = Template:Bigger | list5 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | content1 =

| heading2 = Theorems | content2 =

}}

| list6name = multivariable | list6title = Template:Bigger | list6 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | heading1 = Formalisms | content1 =

| heading2 = Definitions | content2 =

- Partial derivative

- Multiple integral

- Line integral

- Surface integral

- Volume integral

- Jacobian

- Hessian

}}

| list7name = advanced | list7title = Template:Bigger | list7 ={{#invoke:sidebar|sidebar|child=yes

|contentclass=hlist | content1 =

}}

| list8name = specialized | list8title = Template:Bigger | list8 =

| list9name = miscellanea | list9title = Template:Bigger | list9 =

- Precalculus

- History

- Glossary

- List of topics

- Integration Bee

- Mathematical analysis

- Nonstandard analysis

}}

The fundamental theorem of calculus is a theorem that links the concept of differentiating a function (calculating its slopes, or rate of change at each point in time) with the concept of integrating a function (calculating the area under its graph, or the cumulative effect of small contributions). Roughly speaking, the two operations can be thought of as inverses of each other.

The first part of the theorem, the first fundamental theorem of calculus, states that for a continuous function Template:Mvar , an antiderivative or indefinite integral Template:Mvar can be obtained as the integral of Template:Mvar over an interval with a variable upper bound.[1]

Conversely, the second part of the theorem, the second fundamental theorem of calculus, states that the integral of a function Template:Mvar over a fixed interval is equal to the change of any antiderivative Template:Mvar between the ends of the interval. This greatly simplifies the calculation of a definite integral provided an antiderivative can be found by symbolic integration, thus avoiding numerical integration.

History

The fundamental theorem of calculus relates differentiation and integration, showing that these two operations are essentially inverses of one another. Before the discovery of this theorem, it was not recognized that these two operations were related. Ancient Greek mathematicians knew how to compute area via infinitesimals, an operation that we would now call integration. The origins of differentiation likewise predate the fundamental theorem of calculus by hundreds of years; for example, in the fourteenth century the notions of continuity of functions and motion were studied by the Oxford Calculators and other scholars. The historical relevance of the fundamental theorem of calculus is not the ability to calculate these operations, but the realization that the two seemingly distinct operations (calculation of geometric areas, and calculation of gradients) are actually closely related.

From the conjecture and the proof of the fundamental theorem of calculus, calculus as a unified theory of integration and differentiation is started. The first published statement and proof of a rudimentary form of the fundamental theorem, strongly geometric in character,[2] was by James Gregory (1638–1675).[3][4] Isaac Barrow (1630–1677) proved a more generalized version of the theorem,[5] while his student Isaac Newton (1642–1727) completed the development of the surrounding mathematical theory. Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716) systematized the knowledge into a calculus for infinitesimal quantities and introduced the notation used today.

Geometric meaning/Proof

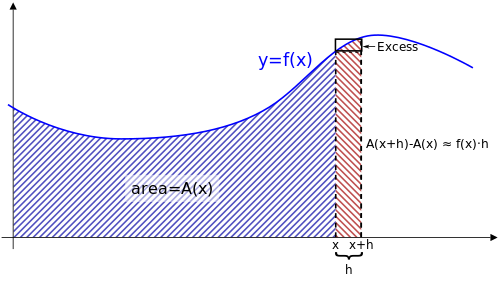

The first fundamental theorem may be interpreted as follows. Given a continuous function whose graph is plotted as a curve, one defines a corresponding "area function" such that Template:Math is the area beneath the curve between Template:Math and Template:Mvar. The area Template:Math may not be easily computable, but it is assumed to be well defined.

The area under the curve between Template:Mvar and Template:Math could be computed by finding the area between Template:Math and Template:Math, then subtracting the area between Template:Math and Template:Mvar. In other words, the area of this "strip" would be Template:Math.

There is another way to estimate the area of this same strip. As shown in the accompanying figure, Template:Mvar is multiplied by Template:Math to find the area of a rectangle that is approximately the same size as this strip. So:

Dividing by h on both sides, we get:

This estimate becomes a perfect equality when h approaches 0: That is, the derivative of the area function Template:Math exists and is equal to the original function Template:Math, so the area function is an antiderivative of the original function.

Thus, the derivative of the integral of a function (the area) is the original function, so that derivative and integral are inverse operations which reverse each other. This is the essence of the Fundamental Theorem.

Physical intuition

Intuitively, the fundamental theorem states that integration and differentiation are inverse operations which reverse each other.

The second fundamental theorem says that the sum of infinitesimal changes in a quantity (the integral of the derivative of the quantity) adds up to the net change in the quantity. To visualize this, imagine traveling in a car and wanting to know the distance traveled (the net change in position along the highway). You can see the velocity on the speedometer but cannot look out to see your location. Each second, you can find how far the car has traveled using Template:Math, that is, multiplying the current speed (in kilometers or miles per hour) by the time interval (1 second = hour). By summing up all these small steps, you can approximate the total distance traveled, in spite of not looking outside the car:As becomes infinitesimally small, the summing up corresponds to integration. Thus, the integral of the velocity function (the derivative of position) computes how far the car has traveled (the net change in position).

The first fundamental theorem says that the value of any function is the rate of change (the derivative) of its integral from a fixed starting point up to any chosen end point. Continuing the above example using a velocity as the function, you can integrate it from the starting time up to any given time to obtain a distance function whose derivative is that velocity. (To obtain your highway-marker position, you would need to add your starting position to this integral and to take into account whether your travel was in the direction of increasing or decreasing mile markers.)

Formal statements

There are two parts to the theorem. The first part deals with the derivative of an antiderivative, while the second part deals with the relationship between antiderivatives and definite integrals.

First part

This part is sometimes referred to as the first fundamental theorem of calculus.[6]

Let Template:Mvar be a continuous real-valued function defined on a closed interval Template:Closed-closed. Let Template:Mvar be the function defined, for all Template:Mvar in Template:Closed-closed, by

Then Template:Mvar is uniformly continuous on Template:Math and differentiable on the open interval Template:Open-open, and for all Template:Mvar in Template:Open-open so Template:Mvar is an antiderivative of Template:Mvar.

Corollary

The fundamental theorem is often employed to compute the definite integral of a function for which an antiderivative is known. Specifically, if is a real-valued continuous function on and is an antiderivative of in , then

The corollary assumes continuity on the whole interval. This result is strengthened slightly in the following part of the theorem.

Second part

This part is sometimes referred to as the second fundamental theorem of calculus[7] or the Newton–Leibniz theorem.

Let be a real-valued function on a closed interval and a continuous function on which is an antiderivative of in :

If is Riemann integrable on then

The second part is somewhat stronger than the corollary because it does not assume that is continuous.

When an antiderivative of exists, then there are infinitely many antiderivatives for , obtained by adding an arbitrary constant to . Also, by the first part of the theorem, antiderivatives of always exist when is continuous.

Proof of the first part

For a given function Template:Math, define the function Template:Math as

For any two numbers Template:Math and Template:Math in Template:Closed-closed, we have

the latter equality resulting from the basic properties of integrals and the additivity of areas.

According to the mean value theorem for integration, there exists a real number such that

It follows that and thus that

Taking the limit as and keeping in mind that one gets that is, according to the definition of the derivative, the continuity of Template:Mvar, and the squeeze theorem.[8]

Proof of the corollary

Suppose Template:Mvar is an antiderivative of Template:Mvar, with Template:Mvar continuous on Template:Closed-closed. Let

By the first part of the theorem, we know Template:Mvar is also an antiderivative of Template:Mvar. Since Template:Math the mean value theorem implies that Template:Math is a constant function, that is, there is a number Template:Mvar such that Template:Math for all Template:Mvar in Template:Closed-closed. Letting Template:Math, we have which means Template:Math. In other words, Template:Math, and so

Proof of the second part

This is a limit proof by Riemann sums.

To begin, we recall the mean value theorem. Stated briefly, if Template:Mvar is continuous on the closed interval Template:Closed-closed and differentiable on the open interval Template:Open-open, then there exists some Template:Mvar in Template:Open-open such that

Let Template:Mvar be (Riemann) integrable on the interval Template:Closed-closed, and let Template:Mvar admit an antiderivative Template:Mvar on Template:Open-open such that Template:Mvar is continuous on Template:Closed-closed. Begin with the quantity Template:Math. Let there be numbers Template:Math such that

It follows that

Now, we add each Template:Math along with its additive inverse, so that the resulting quantity is equal:

The above quantity can be written as the following sum: Template:NumBlk

The function Template:Mvar is differentiable on the interval Template:Open-open and continuous on the closed interval Template:Closed-closed; therefore, it is also differentiable on each interval Template:Open-open and continuous on each interval Template:Closed-closed. According to the mean value theorem (above), for each Template:Mvar there exists a in Template:Open-open such that

Substituting the above into (Template:EquationNote), we get

The assumption implies Also, can be expressed as of partition . Template:NumBlk

We are describing the area of a rectangle, with the width times the height, and we are adding the areas together. Each rectangle, by virtue of the mean value theorem, describes an approximation of the curve section it is drawn over. Also need not be the same for all values of Template:Mvar, or in other words that the width of the rectangles can differ. What we have to do is approximate the curve with Template:Mvar rectangles. Now, as the size of the partitions get smaller and Template:Mvar increases, resulting in more partitions to cover the space, we get closer and closer to the actual area of the curve.

By taking the limit of the expression as the norm of the partitions approaches zero, we arrive at the Riemann integral. We know that this limit exists because Template:Mvar was assumed to be integrable. That is, we take the limit as the largest of the partitions approaches zero in size, so that all other partitions are smaller and the number of partitions approaches infinity.

So, we take the limit on both sides of (Template:EquationNote). This gives us

Neither Template:Math nor Template:Math is dependent on , so the limit on the left side remains Template:Math.

The expression on the right side of the equation defines the integral over Template:Mvar from Template:Mvar to Template:Mvar. Therefore, we obtain which completes the proof.

Relationship between the parts

As discussed above, a slightly weaker version of the second part follows from the first part.

Similarly, it almost looks like the first part of the theorem follows directly from the second. That is, suppose Template:Mvar is an antiderivative of Template:Mvar. Then by the second theorem, . Now, suppose . Then Template:Mvar has the same derivative as Template:Mvar, and therefore Template:Math. This argument only works, however, if we already know that Template:Mvar has an antiderivative, and the only way we know that all continuous functions have antiderivatives is by the first part of the Fundamental Theorem.[9] For example, if Template:Math, then Template:Mvar has an antiderivative, namely and there is no simpler expression for this function. It is therefore important not to interpret the second part of the theorem as the definition of the integral. Indeed, there are many functions that are integrable but lack elementary antiderivatives, and discontinuous functions can be integrable but lack any antiderivatives at all. Conversely, many functions that have antiderivatives are not Riemann integrable (see Volterra's function).

Examples

Computing a particular integral

Suppose the following is to be calculated:

Here, and we can use as the antiderivative. Therefore:

Using the first part

Suppose is to be calculated. Using the first part of the theorem with gives

This can also be checked using the second part of the theorem. Specifically, is an antiderivative of , so

An integral where the corollary is insufficient

Suppose Then is not continuous at zero. Moreover, this is not just a matter of how is defined at zero, since the limit as of does not exist. Therefore, the corollary cannot be used to compute But consider the function Notice that is continuous on (including at zero by the squeeze theorem), and is differentiable on with Therefore, part two of the theorem applies, and

Theoretical example

The theorem can be used to prove that

Since, the result follows from,

Generalizations

The function Template:Mvar does not have to be continuous over the whole interval. Part I of the theorem then says: if Template:Mvar is any Lebesgue integrable function on Template:Closed-closed and Template:Math is a number in Template:Closed-closed such that Template:Mvar is continuous at Template:Math, then

is differentiable for Template:Math with Template:Math. We can relax the conditions on Template:Mvar still further and suppose that it is merely locally integrable. In that case, we can conclude that the function Template:Mvar is differentiable almost everywhere and Template:Math almost everywhere. On the real line this statement is equivalent to Lebesgue's differentiation theorem. These results remain true for the Henstock–Kurzweil integral, which allows a larger class of integrable functions.Template:Sfnp

In higher dimensions Lebesgue's differentiation theorem generalizes the Fundamental theorem of calculus by stating that for almost every Template:Mvar, the average value of a function Template:Mvar over a ball of radius Template:Mvar centered at Template:Mvar tends to Template:Math as Template:Mvar tends to 0.

Part II of the theorem is true for any Lebesgue integrable function Template:Mvar, which has an antiderivative Template:Mvar (not all integrable functions do, though). In other words, if a real function Template:Mvar on Template:Closed-closed admits a derivative Template:Math at every point Template:Mvar of Template:Closed-closed and if this derivative Template:Mvar is Lebesgue integrable on Template:Closed-closed, then[10]

This result may fail for continuous functions Template:Mvar that admit a derivative Template:Math at almost every point Template:Mvar, as the example of the Cantor function shows. However, if Template:Mvar is absolutely continuous, it admits a derivative Template:Math at almost every point Template:Mvar, and moreover Template:Mvar is integrable, with Template:Math equal to the integral of Template:Mvar on Template:Closed-closed. Conversely, if Template:Mvar is any integrable function, then Template:Mvar as given in the first formula will be absolutely continuous with Template:Math almost everywhere.

The conditions of this theorem may again be relaxed by considering the integrals involved as Henstock–Kurzweil integrals. Specifically, if a continuous function Template:Math admits a derivative Template:Math at all but countably many points, then Template:Math is Henstock–Kurzweil integrable and Template:Math is equal to the integral of Template:Mvar on Template:Closed-closed. The difference here is that the integrability of Template:Mvar does not need to be assumed.Template:Sfnp

The version of Taylor's theorem that expresses the error term as an integral can be seen as a generalization of the fundamental theorem.

There is a version of the theorem for complex functions: suppose Template:Mvar is an open set in Template:Math and Template:Math is a function that has a holomorphic antiderivative Template:Mvar on Template:Mvar. Then for every curve Template:Math, the curve integral can be computed as

The fundamental theorem can be generalized to curve and surface integrals in higher dimensions and on manifolds. One such generalization offered by the calculus of moving surfaces is the time evolution of integrals. The most familiar extensions of the fundamental theorem of calculus in higher dimensions are the divergence theorem and the gradient theorem.

One of the most powerful generalizations in this direction is the generalized Stokes theorem (sometimes known as the fundamental theorem of multivariable calculus):[11] Let Template:Mvar be an oriented piecewise smooth manifold of dimension Template:Mvar and let be a smooth compactly supported [[differential form|Template:Math-form]] on Template:Mvar. If Template:Math denotes the boundary of Template:Mvar given its induced orientation, then

Here Template:Math is the exterior derivative, which is defined using the manifold structure only.

The theorem is often used in situations where Template:Mvar is an embedded oriented submanifold of some bigger manifold (e.g. Template:Math) on which the form is defined.

The fundamental theorem of calculus allows us to pose a definite integral as a first-order ordinary differential equation. can be posed as with as the value of the integral.

See also

- Differentiation under the integral sign

- Telescoping series

- Fundamental theorem of calculus for line integrals

- Notation for differentiation

Notes

References

Bibliography

Further reading

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

- Malet, A., Studies on James Gregorie (1638-1675) (PhD Thesis, Princeton, 1989).

- Hernandez Rodriguez, O. A.; Lopez Fernandez, J. M. . "Teaching the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus: A Historical Reflection", Loci: Convergence (MAA), January 2012.

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation.

External links

- Template:Springer

- James Gregory's Euclidean Proof of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus at Convergence

- Isaac Barrow's proof of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus

- Fundamental Theorem of Calculus at imomath.com

- Alternative proof of the fundamental theorem of calculus

- Fundamental Theorem of Calculus MIT.

- Fundamental Theorem of Calculus Mathworld.

Template:Calculus topics Template:Analysis-footer Template:Authority control

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ See, e.g., Marlow Anderson, Victor J. Katz, Robin J. Wilson, Sherlock Holmes in Babylon and Other Tales of Mathematical History, Mathematical Association of America, 2004, p. 114.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Citation.

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Cite book