Faraday's law of induction

Template:Short description Template:Use American English

Faraday's law of induction (or simply Faraday's law) is a law of electromagnetism predicting how a magnetic field will interact with an electric circuit to produce an electromotive force (emf). This phenomenon, known as electromagnetic induction, is the fundamental operating principle of transformers, inductors, and many types of electric motors, generators and solenoids.[2][3]

The Maxwell–Faraday equation (listed as one of Maxwell's equations) describes the fact that a spatially varying (and also possibly time-varying, depending on how a magnetic field varies in time) electric field always accompanies a time-varying magnetic field, while Faraday's law states that emf (electromagnetic work done on a unit charge when it has traveled one round of a conductive loop) appears on a conductive loop when the magnetic flux through the surface enclosed by the loop varies in time.

Once Faraday's law had been discovered, one aspect of it (transformer emf) was formulated as the Maxwell–Faraday equation. The equation of Faraday's law can be derived by the Maxwell–Faraday equation (describing transformer emf) and the Lorentz force (describing motional emf). The integral form of the Maxwell–Faraday equation describes only the transformer emf, while the equation of Faraday's law describes both the transformer emf and the motional emf.

History

Electromagnetic induction was discovered independently by Michael Faraday in 1831 and Joseph Henry in 1832.[4] Faraday was the first to publish the results of his experiments.[5][6]

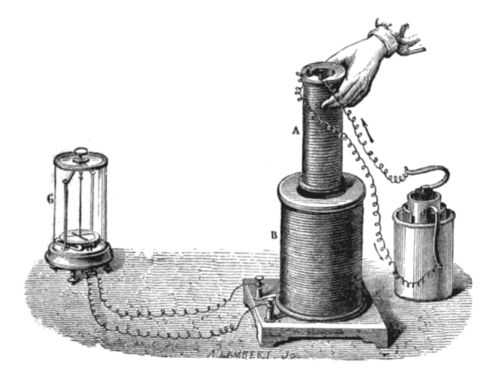

Faraday's notebook on August 29, 1831[8] describes an experimental demonstration of electromagnetic induction (see figure)[9] that wraps two wires around opposite sides of an iron ring (like a modern toroidal transformer). His assessment of newly-discovered properties of electromagnets suggested that when current started to flow in one wire, a sort of wave would travel through the ring and cause some electrical effect on the opposite side. Indeed, a galvanometer's needle measured a transient current (which he called a "wave of electricity") on the right side's wire when he connected or disconnected the left side's wire to a battery.[10]Template:Rp This induction was due to the change in magnetic flux that occurred when the battery was connected and disconnected.[7] His notebook entry also noted that fewer wraps for the battery side resulted in a greater disturbance of the galvanometer's needle.[8]

Within two months, Faraday had found several other manifestations of electromagnetic induction. For example, he saw transient currents when he quickly slid a bar magnet in and out of a coil of wires, and he generated a steady (DC) current by rotating a copper disk near the bar magnet with a sliding electrical lead ("Faraday's disk").[10]Template:Rp

Michael Faraday explained electromagnetic induction using a concept he called lines of force. However, scientists at the time widely rejected his theoretical ideas, mainly because they were not formulated mathematically.[10]Template:Rp An exception was James Clerk Maxwell, who in 1861–62 used Faraday's ideas as the basis of his quantitative electromagnetic theory.[10]Template:Rp[11][12] In Maxwell's papers, the time-varying aspect of electromagnetic induction is expressed as a differential equation which Oliver Heaviside referred to as Faraday's law even though it is different from the original version of Faraday's law, and does not describe motional emf. Heaviside's version (see Maxwell–Faraday equation below) is the form recognized today in the group of equations known as Maxwell's equations.

Lenz's law, formulated by Emil Lenz in 1834,[13] describes "flux through the circuit", and gives the direction of the induced emf and current resulting from electromagnetic induction (elaborated upon in the examples below).

According to Albert Einstein, much of the groundwork and discovery of his special relativity theory was presented by this law of induction by Faraday in 1834.[14][15] Template:Clear

Faraday's law

The most widespread version of Faraday's law states: Template:Blockquote

Mathematical statement

For a loop of wire in a magnetic field, the magnetic flux Template:Math is defined for any surface Template:Math whose boundary is the given loop. Since the wire loop may be moving, we write Template:Math for the surface. The magnetic flux is the surface integral: where Template:Math is an element of area vector of the moving surface Template:Math, Template:Math is the magnetic field, and Template:Math is a vector dot product representing the element of flux through Template:Math. In more visual terms, the magnetic flux through the wire loop is proportional to the number of magnetic field lines that pass through the loop.

When the flux changes—because Template:Math changes, or because the wire loop is moved or deformed, or both—Faraday's law of induction says that the wire loop acquires an emf, defined as the energy available from a unit charge that has traveled once around the wire loop.[16]Template:Rp[17][18] (Although some sources state the definition differently, this expression was chosen for compatibility with the equations of special relativity.) Equivalently, it is the voltage that would be measured by cutting the wire to create an open circuit, and attaching a voltmeter to the leads.

Faraday's law states that the emf is also given by the rate of change of the magnetic flux: where is the electromotive force (emf) and Template:Math is the magnetic flux.

The direction of the electromotive force is given by Lenz's law.

The laws of induction of electric currents in mathematical form were established by Franz Ernst Neumann in 1845.[19]

Faraday's law contains the information about the relationships between both the magnitudes and the directions of its variables. However, the relationships between the directions are not explicit; they are hidden in the mathematical formula.

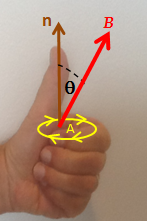

It is possible to find out the direction of the electromotive force (emf) directly from Faraday’s law, without invoking Lenz's law. A left hand rule helps doing that, as follows:[20][21]

- Align the curved fingers of the left hand with the loop (yellow line).

- Stretch your thumb. The stretched thumb indicates the direction of Template:Math (brown), the normal to the area enclosed by the loop.

- Find the sign of Template:Math, the change in flux. Determine the initial and final fluxes (whose difference is Template:Math) with respect to the normal Template:Math, as indicated by the stretched thumb.

- If the change in flux, Template:Math, is positive, the curved fingers show the direction of the electromotive force (yellow arrowheads).

- If Template:Math is negative, the direction of the electromotive force is opposite to the direction of the curved fingers (opposite to the yellow arrowheads).

For a tightly wound coil of wire, composed of Template:Mvar identical turns, each with the same Template:Math, Faraday's law of induction states that[22][23] where Template:Mvar is the number of turns of wire and Template:Math is the magnetic flux through a single loop.

Maxwell–Faraday equation

The Maxwell–Faraday equation states that a time-varying magnetic field always accompanies a spatially varying (also possibly time-varying), non-conservative electric field, and vice versa. The Maxwell–Faraday equation is

(in SI units) where Template:Math is the curl operator and again Template:Math is the electric field and Template:Math is the magnetic field. These fields can generally be functions of position Template:Math and time Template:Mvar.[24]

The Maxwell–Faraday equation is one of the four Maxwell's equations, and therefore plays a fundamental role in the theory of classical electromagnetism. It can also be written in an integral form by the Kelvin–Stokes theorem,[25] thereby reproducing Faraday's law:

where, as indicated in the figure, Template:Math is a surface bounded by the closed contour Template:Math, Template:Math is an infinitesimal vector element of the contour Template:Math, and Template:Math is an infinitesimal vector element of surface Template:Math. Its direction is orthogonal to that surface patch, the magnitude is the area of an infinitesimal patch of surface.

Both Template:Math and Template:Math have a sign ambiguity; to get the correct sign, the right-hand rule is used, as explained in the article Kelvin–Stokes theorem. For a planar surface Template:Math, a positive path element Template:Math of curve Template:Math is defined by the right-hand rule as one that points with the fingers of the right hand when the thumb points in the direction of the normal Template:Math to the surface Template:Math.

The line integral around Template:Math is called circulation.[16]Template:Rp A nonzero circulation of Template:Math is different from the behavior of the electric field generated by static charges. A charge-generated Template:Math-field can be expressed as the gradient of a scalar field that is a solution to Poisson's equation, and has a zero path integral. See gradient theorem.

The integral equation is true for any path Template:Math through space, and any surface Template:Math for which that path is a boundary.

If the surface Template:Math is not changing in time, the equation can be rewritten: The surface integral at the right-hand side is the explicit expression for the magnetic flux Template:Math through Template:Math.

The electric vector field induced by a changing magnetic flux, the solenoidal component of the overall electric field, can be approximated in the non-relativistic limit by the volume integral equation[24]Template:Rp

Proof

The four Maxwell's equations (including the Maxwell–Faraday equation), along with Lorentz force law, are a sufficient foundation to derive everything in classical electromagnetism.[16][17] Therefore, it is possible to "prove" Faraday's law starting with these equations.[26][27]

The starting point is the time-derivative of flux through an arbitrary surface Template:Math (that can be moved or deformed) in space:

(by definition). This total time derivative can be evaluated and simplified with the help of the Maxwell–Faraday equation and some vector identities; the details are in the box below:

| Consider the time-derivative of magnetic flux through a closed boundary (loop) that can move or be deformed. The area bounded by the loop is denoted as Template:Math), then the time-derivative can be expressed as

The integral can change over time for two reasons: The integrand can change, or the integration region can change. These add linearly, therefore: where Template:Math is any given fixed time. We will show that the first term on the right-hand side corresponds to transformer emf, the second to motional emf (from the magnetic Lorentz force on charge carriers due to the motion or deformation of the conducting loop in the magnetic field). The first term on the right-hand side can be rewritten using the integral form of the Maxwell–Faraday equation: Next, we analyze the second term on the right-hand side:  Here, identities of triple scalar products are used. Therefore, where Template:Math is the velocity of a part of the loop Template:Math. Putting these together results in, |

The result is: where Template:Math is the boundary (loop) of the surface Template:Math, and Template:Math is the velocity of a part of the boundary.

In the case of a conductive loop, emf (Electromotive Force) is the electromagnetic work done on a unit charge when it has traveled around the loop once, and this work is done by the Lorentz force. Therefore, emf is expressed as where is emf and Template:Math is the unit charge velocity.

In a macroscopic view, for charges on a segment of the loop, Template:Math consists of two components in average; one is the velocity of the charge along the segment Template:Math, and the other is the velocity of the segment Template:Math (the loop is deformed or moved). Template:Math does not contribute to the work done on the charge since the direction of Template:Math is same to the direction of . Mathematically, since is perpendicular to as and are along the same direction. Now we can see that, for the conductive loop, emf is same to the time-derivative of the magnetic flux through the loop except for the sign on it. Therefore, we now reach the equation of Faraday's law (for the conductive loop) as where . With breaking this integral, is for the transformer emf (due to a time-varying magnetic field) and is for the motional emf (due to the magnetic Lorentz force on charges by the motion or deformation of the loop in the magnetic field).

Exceptions

Template:See also It is tempting to generalize Faraday's law to state: If Template:Math is any arbitrary closed loop in space whatsoever, then the total time derivative of magnetic flux through Template:Math equals the emf around Template:Math. This statement, however, is not always true and the reason is not just from the obvious reason that emf is undefined in empty space when no conductor is present. As noted in the previous section, Faraday's law is not guaranteed to work unless the velocity of the abstract curve Template:Math matches the actual velocity of the material conducting the electricity.[29] The two examples illustrated below show that one often obtains incorrect results when the motion of Template:Math is divorced from the motion of the material.[16]

-

Faraday's homopolar generator. The disc rotates with angular rate Template:Mvar, sweeping the conducting radius circularly in the static magnetic field Template:Math (which direction is along the disk surface normal). The magnetic Lorentz force Template:Math drives a current along the conducting radius to the conducting rim, and from there the circuit completes through the lower brush and the axle supporting the disc. This device generates an emf and a current, although the shape of the "circuit" is constant and thus the flux through the circuit does not change with time.

-

A wire (solid red lines) connects to two touching metal plates (silver) to form a circuit. The whole system sits in a uniform magnetic field, normal to the page. If the abstract path Template:Math follows the primary path of current flow (marked in red), then the magnetic flux through this path changes dramatically as the plates are rotated, yet the emf is almost zero. After Feynman Lectures on Physics[16]Template:Rp

One can analyze examples like these by taking care that the path Template:Math moves with the same velocity as the material.[29] Alternatively, one can always correctly calculate the emf by combining Lorentz force law with the Maxwell–Faraday equation:[16]Template:Rp[30]

where "it is very important to notice that (1) Template:Math is the velocity of the conductor ... not the velocity of the path element Template:Math and (2) in general, the partial derivative with respect to time cannot be moved outside the integral since the area is a function of time."[30]

Faraday's law and relativity

Two phenomena

Faraday's law is a single equation describing two different phenomena: the motional emf generated by a magnetic force on a moving wire (see the Lorentz force), and the transformer emf generated by an electric force due to a changing magnetic field (described by the Maxwell–Faraday equation).

James Clerk Maxwell drew attention to this fact in his 1861 paper On Physical Lines of Force.[31] In the latter half of Part II of that paper, Maxwell gives a separate physical explanation for each of the two phenomena.

A reference to these two aspects of electromagnetic induction is made in some modern textbooks.[32] As Richard Feynman states:

Template:BlockquoteTemplate:Dubious

Explanation based on four-dimensional formalism

In the general case, explanation of the motional emf appearance by action of the magnetic force on the charges in the moving wire or in the circuit changing its area is unsatisfactory. As a matter of fact, the charges in the wire or in the circuit could be completely absent, will then the electromagnetic induction effect disappear in this case? This situation is analyzed in the article, in which, when writing the integral equations of the electromagnetic field in a four-dimensional covariant form, in the Faraday’s law the total time derivative of the magnetic flux through the circuit appears instead of the partial time derivative.[33] Thus, electromagnetic induction appears either when the magnetic field changes over time or when the area of the circuit changes. From the physical point of view, it is better to speak not about the induction emf, but about the induced electric field strength , that occurs in the circuit when the magnetic flux changes. In this case, the contribution to from the change in the magnetic field is made through the term , where is the vector potential. If the circuit area is changing in case of the constant magnetic field, then some part of the circuit is inevitably moving, and the electric field emerges in this part of the circuit in the comoving reference frame K’ as a result of the Lorentz transformation of the magnetic field , present in the stationary reference frame K, which passes through the circuit. The presence of the field in K’ is considered as a result of the induction effect in the moving circuit, regardless of whether the charges are present in the circuit or not. In the conducting circuit, the field causes motion of the charges. In the reference frame K, it looks like appearance of emf of the induction , the gradient of which in the form of , taken along the circuit, seems to generate the field .

Einstein's view

Reflection on this apparent dichotomy was one of the principal paths that led Albert Einstein to develop special relativity: Template:Blockquote

See also

Template:Columns-listTemplate:Clear

References

Further reading

External links

- Template:Commons category-inline

- A simple interactive tutorial on electromagnetic induction (click and drag magnet back and forth) National High Magnetic Field Laboratory

- Roberto Vega. Induction: Faraday's law and Lenz's law – Highly animated lecture, with sound effects, Electricity and Magnetism course page

- Notes from Physics and Astronomy HyperPhysics at Georgia State University

- Tankersley and Mosca: Introducing Faraday's law

- A free simulation on motional emf

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Template:Cite bookTemplate:Full citation needed

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

A partial translation of the paper is available in Template:Cite book - ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Template:Cite web

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Template:Cite journal Video Explanation

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

Note that the law relating flux to emf, which this article calls "Faraday's law", is referred to in Griffiths' terminology as the "universal flux rule". Griffiths uses the term "Faraday's law" to refer to what this article calls the "Maxwell–Faraday equation". So in fact, in the textbook, Griffiths' statement is about the "universal flux rule". - ↑ Template:Cite journal