Fourier series

Template:Short description Template:Redirect Template:Fourier transforms A Fourier series (Template:IPAc-en[1]) is an expansion of a periodic function into a sum of trigonometric functions. The Fourier series is an example of a trigonometric series.Template:Sfn By expressing a function as a sum of sines and cosines, many problems involving the function become easier to analyze because trigonometric functions are well understood. For example, Fourier series were first used by Joseph Fourier to find solutions to the heat equation. This application is possible because the derivatives of trigonometric functions fall into simple patterns. Fourier series cannot be used to approximate arbitrary functions, because most functions have infinitely many terms in their Fourier series, and the series do not always converge. Well-behaved functions, for example smooth functions, have Fourier series that converge to the original function. The coefficients of the Fourier series are determined by integrals of the function multiplied by trigonometric functions, described in Template:Slink.

The study of the convergence of Fourier series focus on the behaviors of the partial sums, which means studying the behavior of the sum as more and more terms from the series are summed. The figures below illustrate some partial Fourier series results for the components of a square wave.

-

A square wave (represented as the blue dot) is approximated by its sixth partial sum (represented as the purple dot), formed by summing the first six terms (represented as arrows) of the square wave's Fourier series. Each arrow starts at the vertical sum of all the arrows to its left (i.e. the previous partial sum).

-

The first four partial sums of the Fourier series for a square wave. As more harmonics are added, the partial sums converge to (become more and more like) the square wave.

-

Function (in red) is a Fourier series sum of 6 harmonically related sine waves (in blue). Its Fourier transform is a frequency-domain representation that reveals the amplitudes of the summed sine waves.

Fourier series are closely related to the Fourier transform, a more general tool that can even find the frequency information for functions that are not periodic. Periodic functions can be identified with functions on a circle; for this reason Fourier series are the subject of Fourier analysis on the circle group, denoted by or . The Fourier transform is also part of Fourier analysis, but is defined for functions on .

Since Fourier's time, many different approaches to defining and understanding the concept of Fourier series have been discovered, all of which are consistent with one another, but each of which emphasizes different aspects of the topic. Some of the more powerful and elegant approaches are based on mathematical ideas and tools that were not available in Fourier's time. Fourier originally defined the Fourier series for real-valued functions of real arguments, and used the sine and cosine functions in the decomposition. Many other Fourier-related transforms have since been defined, extending his initial idea to many applications and birthing an area of mathematics called Fourier analysis.

HistoryTemplate:Anchor

The Fourier series is named in honor of Jean-Baptiste Joseph Fourier (1768–1830), who made important contributions to the study of trigonometric series, after preliminary investigations by Leonhard Euler, Jean le Rond d'Alembert, and Daniel Bernoulli.Template:Efn-ua Fourier introduced the series for the purpose of solving the heat equation in a metal plate, publishing his initial results in his 1807 Mémoire sur la propagation de la chaleur dans les corps solides (Treatise on the propagation of heat in solid bodies), and publishing his Théorie analytique de la chaleur (Analytical theory of heat) in 1822. The Mémoire introduced Fourier analysis, specifically Fourier series. Through Fourier's research the fact was established that an arbitrary (at first, continuous[2] and later generalized to any piecewise-smooth[3]) function can be represented by a trigonometric series. The first announcement of this great discovery was made by Fourier in 1807, before the French Academy.[4] Early ideas of decomposing a periodic function into the sum of simple oscillating functions date back to the 3rd century BC, when ancient astronomers proposed an empiric model of planetary motions, based on deferents and epicycles.

Independently of Fourier, astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel introduced Fourier series to solve Kepler's equation. His work was published in 1819, unaware of Fourier's work which remained unpublished until 1822.[5]

The heat equation is a partial differential equation. Prior to Fourier's work, no solution to the heat equation was known in the general case, although particular solutions were known if the heat source behaved in a simple way, in particular, if the heat source was a sine or cosine wave. These simple solutions are now sometimes called eigensolutions. Fourier's idea was to model a complicated heat source as a superposition (or linear combination) of simple sine and cosine waves, and to write the solution as a superposition of the corresponding eigensolutions. This superposition or linear combination is called the Fourier series.

From a modern point of view, Fourier's results are somewhat informal, due to the lack of a precise notion of function and integral in the early nineteenth century. Later, Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet[6] and Bernhard Riemann[7][8][9] expressed Fourier's results with greater precision and formality.

Although the original motivation was to solve the heat equation, it later became obvious that the same techniques could be applied to a wide array of mathematical and physical problems, and especially those involving linear differential equations with constant coefficients, for which the eigensolutions are sinusoids. The Fourier series has many such applications in electrical engineering, vibration analysis, acoustics, optics, signal processing, image processing, quantum mechanics, econometrics,[10] shell theory,[11] etc.

Beginnings

Joseph Fourier wrote[12]

This immediately gives any coefficient ak of the trigonometric series for φ(y) for any function which has such an expansion. It works because if φ has such an expansion, then (under suitable convergence assumptions) the integral can be carried out term-by-term. But all terms involving for Template:Nowrap vanish when integrated from −1 to 1, leaving only the term, which is 1.

In these few lines, which are close to the modern formalism used in Fourier series, Fourier revolutionized both mathematics and physics. Although similar trigonometric series were previously used by Euler, d'Alembert, Daniel Bernoulli and Gauss, Fourier believed that such trigonometric series could represent any arbitrary function. In what sense that is actually true is a somewhat subtle issue and the attempts over many years to clarify this idea have led to important discoveries in the theories of convergence, function spaces, and harmonic analysis.

When Fourier submitted a later competition essay in 1811, the committee (which included Lagrange, Laplace, Malus and Legendre, among others) concluded: ...the manner in which the author arrives at these equations is not exempt of difficulties and...his analysis to integrate them still leaves something to be desired on the score of generality and even rigour.[13]

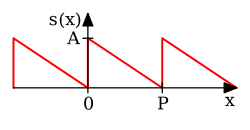

Fourier's motivation

The Fourier series expansion of the sawtooth function (below) looks more complicated than the simple formula , so it is not immediately apparent why one would need the Fourier series. While there are many applications, Fourier's motivation was in solving the heat equation. For example, consider a metal plate in the shape of a square whose sides measure meters, with coordinates . If there is no heat source within the plate, and if three of the four sides are held at 0 degrees Celsius, while the fourth side, given by , is maintained at the temperature gradient degrees Celsius, for in , then one can show that the stationary heat distribution (or the heat distribution after a long time has elapsed) is given by

Here, sinh is the hyperbolic sine function. This solution of the heat equation is obtained by multiplying each term of the equation from Analysis § Example by . While our example function seems to have a needlessly complicated Fourier series, the heat distribution is nontrivial. The function cannot be written as a closed-form expression. This method of solving the heat problem was made possible by Fourier's work.

Other applications

Another application is to solve the Basel problem by using Parseval's theorem. The example generalizes and one may compute ζ(2n), for any positive integer n.

Definition

The Fourier series of a complex-valued Template:Math-periodic function , integrable over the interval on the real line, is defined as a trigonometric series of the form such that the Fourier coefficients are complex numbers defined by the integralTemplate:SfnTemplate:Sfn The series does not necessarily converge (in the pointwise sense) and, even if it does, it is not necessarily equal to . Only when certain conditions are satisfied (e.g. if is continuously differentiable) does the Fourier series converge to , i.e., For functions satisfying the Dirichlet sufficiency conditions, pointwise convergence holds.Template:Sfn However, these are not necessary conditions and there are many theorems about different types of convergence of Fourier series (e.g. uniform convergence or mean convergence).Template:Sfn The definition naturally extends to the Fourier series of a (periodic) distribution (also called Fourier-Schwartz series).Template:Sfn Then the Fourier series converges to in the distribution sense.Template:Sfn

The process of determining the Fourier coefficients of a given function or signal is called analysis, while forming the associated trigonometric series (or its various approximations) is called synthesis.

Synthesis

A Fourier series can be written in several equivalent forms, shown here as the partial sums of the Fourier series of :[14]

The harmonics are indexed by an integer, which is also the number of cycles the corresponding sinusoids make in interval . Therefore, the sinusoids have:

- a wavelength equal to in the same units as .

- a frequency equal to in the reciprocal units of .

These series can represent functions that are just a sum of one or more frequencies in the harmonic spectrum. In the limit , a trigonometric series can also represent the intermediate frequencies and/or non-sinusoidal functions because of the infinite number of terms.

Analysis

The coefficients can be given/assumed, such as a music synthesizer or time samples of a waveform. In the latter case, the exponential form of Fourier series synthesizes a discrete-time Fourier transform where variable represents frequency instead of time. In general, the coefficients are determined by analysis of a given function whose domain of definition is an interval of length .Template:Efn-uaTemplate:Sfn

The scale factor follows from substituting Template:EquationNote into Template:EquationNote and utilizing the orthogonality of the trigonometric system.[15] The equivalence of Template:EquationNote and Template:EquationNote follows from Euler's formula resulting in:

with being the mean value of on the interval .Template:Sfn Conversely:

Example

Consider a sawtooth function: In this case, the Fourier coefficients are given by It can be shown that the Fourier series converges to at every point where is differentiable, and therefore: When , the Fourier series converges to 0, which is the half-sum of the left- and right-limit of at . This is a particular instance of the Dirichlet theorem for Fourier series.

This example leads to a solution of the Basel problem.

Amplitude-phase form

If the function is real-valued then the Fourier series can also be represented asTemplate:Sfn

where is the amplitude and is the phase shift of the harmonic.

The equivalence of Template:EquationNote and Template:EquationNote follows from the trigonometric identity: which implies[16]

are the rectangular coordinates of a vector with polar coordinates and given by where is the argument of .

An example of determining the parameter for one value of is shown in Figure 2. It is the value of at the maximum correlation between and a cosine template, The blue graph is the cross-correlation function, also known as a matched filter:

Fortunately, it isn't necessary to evaluate this entire function, because its derivative is zero at the maximum: Hence

Common notations

The notation is inadequate for discussing the Fourier coefficients of several different functions. Therefore, it is customarily replaced by a modified form of the function ( in this case), such as or and functional notation often replaces subscripting:

In engineering, particularly when the variable represents time, the coefficient sequence is called a frequency domain representation. Square brackets are often used to emphasize that the domain of this function is a discrete set of frequencies.

Another commonly used frequency domain representation uses the Fourier series coefficients to modulate a Dirac comb:

where represents a continuous frequency domain. When variable has units of seconds, has units of hertz. The "teeth" of the comb are spaced at multiples (i.e. harmonics) of , which is called the fundamental frequency. can be recovered from this representation by an inverse Fourier transform:

The constructed function is therefore commonly referred to as a Fourier transform, even though the Fourier integral of a periodic function is not convergent at the harmonic frequencies.Template:Efn-ua

Table of common Fourier series

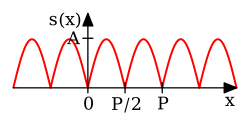

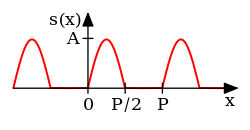

Some common pairs of periodic functions and their Fourier series coefficients are shown in the table below.

- designates a periodic function with period

- designate the Fourier series coefficients (sine-cosine form) of the periodic function

| Time domain

|

Plot | Frequency domain (sine-cosine form)

|

Remarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Full-wave rectified sine | [17]Template:Rp | ||

|

Half-wave rectified sine | [17]Template:Rp | ||

|

||||

|

[17]Template:Rp | |||

|

[17]Template:Rp | |||

|

[17]Template:Rp |

Table of basic transformation rules

Template:See also This table shows some mathematical operations in the time domain and the corresponding effect in the Fourier series coefficients. Notation:

- Complex conjugation is denoted by an asterisk.

- designate -periodic functions or functions defined only for

- designate the Fourier series coefficients (exponential form) of and

| Property | Time domain | Frequency domain (exponential form) | Remarks | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linearity | ||||

| Time reversal / Frequency reversal | [18]Template:Rp | |||

| Time conjugation | [18]Template:Rp | |||

| Time reversal & conjugation | ||||

| Real part in time | ||||

| Imaginary part in time | ||||

| Real part in frequency | ||||

| Imaginary part in frequency | ||||

| Shift in time / Modulation in frequency | [18]Template:Rp | |||

| Shift in frequency / Modulation in time | [18]Template:Rp |

Properties

Symmetry relations

When the real and imaginary parts of a complex function are decomposed into their even and odd parts, there are four components, denoted below by the subscripts RE, RO, IE, and IO. And there is a one-to-one mapping between the four components of a complex time function and the four components of its complex frequency transform:Template:SfnTemplate:Sfn

From this, various relationships are apparent, for example:

- The transform of a real-valued function is the conjugate symmetric function Conversely, a conjugate symmetric transform implies a real-valued time-domain.

- The transform of an imaginary-valued function is the conjugate antisymmetric function and the converse is true.

- The transform of a conjugate symmetric function is the real-valued function and the converse is true.

- The transform of a conjugate antisymmetric function is the imaginary-valued function and the converse is true.

Riemann–Lebesgue lemma

Template:Main If is integrable, , and

Parseval's theorem

Template:Main If belongs to (periodic over an interval of length ) then:

Plancherel's theorem

Template:Main If are coefficients and then there is a unique function such that for every .

Convolution theorems

Given -periodic functions, and with Fourier series coefficients and

- The pointwise product: is also -periodic, and its Fourier series coefficients are given by the discrete convolution of the and sequences:

- The periodic convolution: is also -periodic, with Fourier series coefficients:

- A doubly infinite sequence in is the sequence of Fourier coefficients of a function in if and only if it is a convolution of two sequences in . See [19]

Derivative property

If is a 2Template:Pi-periodic function on which is times differentiable, and its derivative is continuous, then belongs to the function space .

- If , then the Fourier coefficients of the derivative of can be expressed in terms of the Fourier coefficients of , via the formula In particular, since for any fixed we have as , it follows that tends to zero, i.e., the Fourier coefficients converge to zero faster than the power of .

Compact groups

One of the interesting properties of the Fourier transform which we have mentioned, is that it carries convolutions to pointwise products. If that is the property which we seek to preserve, one can produce Fourier series on any compact group. Typical examples include those classical groups that are compact. This generalizes the Fourier transform to all spaces of the form L2(G), where G is a compact group, in such a way that the Fourier transform carries convolutions to pointwise products. The Fourier series exists and converges in similar ways to the Template:Closed-closed case.

An alternative extension to compact groups is the Peter–Weyl theorem, which proves results about representations of compact groups analogous to those about finite groups.

Riemannian manifolds

If the domain is not a group, then there is no intrinsically defined convolution. However, if is a compact Riemannian manifold, it has a Laplace–Beltrami operator. The Laplace–Beltrami operator is the differential operator that corresponds to Laplace operator for the Riemannian manifold . Then, by analogy, one can consider heat equations on . Since Fourier arrived at his basis by attempting to solve the heat equation, the natural generalization is to use the eigensolutions of the Laplace–Beltrami operator as a basis. This generalizes Fourier series to spaces of the type , where is a Riemannian manifold. The Fourier series converges in ways similar to the case. A typical example is to take to be the sphere with the usual metric, in which case the Fourier basis consists of spherical harmonics.

Locally compact Abelian groups

The generalization to compact groups discussed above does not generalize to noncompact, nonabelian groups. However, there is a straightforward generalization to Locally Compact Abelian (LCA) groups.

This generalizes the Fourier transform to or , where is an LCA group. If is compact, one also obtains a Fourier series, which converges similarly to the case, but if is noncompact, one obtains instead a Fourier integral. This generalization yields the usual Fourier transform when the underlying locally compact Abelian group is .

Extensions

Fourier-Stieltjes series

Template:See also Let be a function of bounded variation defined on the closed inverval . The Fourier series whose coefficients are given byTemplate:Sfn is called the Fourier-Stieltjes series. The space of functions of bounded variation is a subspace of . As any defines a Radon measure (i.e. a locally finite Borel measure on ), this definition can be extended as follows.

Consider the space of all finite Borel measures on the real line; as such .Template:Sfn If there is a measure such that the Fourier-Stieltjes coefficients are given by then the series is called a Fourier-Stieltjes series. Likewise, the function , where , is called a Fourier-Stieltjes transform.Template:Sfn

The question whether or not exists for a given sequence of forms the basis of the trigonometric moment problem.Template:Sfn

Furthermore, is a strict subspace of the space of (tempered) distributions , i.e., . If the Fourier coefficients are determined by a distribution then the series is described as a Fourier-Schwartz series. Contrary to the Fourier-Stieltjes series, deciding whether a given series is a Fourier series or a Fourier-Schwartz series is relatively trivial due to the characteristics of its dual space; the Schwartz space .Template:Sfn

Fourier series on a square

We can also define the Fourier series for functions of two variables and in the square :

Aside from being useful for solving partial differential equations such as the heat equation, one notable application of Fourier series on the square is in image compression. In particular, the JPEG image compression standard uses the two-dimensional discrete cosine transform, a discrete form of the Fourier cosine transform, which uses only cosine as the basis function.

For two-dimensional arrays with a staggered appearance, half of the Fourier series coefficients disappear, due to additional symmetry.[20]

Fourier series of Bravais-lattice-periodic-function

A three-dimensional Bravais lattice is defined as the set of vectors of the form: where are integers and are three linearly independent vectors. Assuming we have some function, , such that it obeys the condition of periodicity for any Bravais lattice vector , , we could make a Fourier series of it. This kind of function can be, for example, the effective potential that one electron "feels" inside a periodic crystal. It is useful to make the Fourier series of the potential when applying Bloch's theorem. First, we may write any arbitrary position vector in the coordinate-system of the lattice: where meaning that is defined to be the magnitude of , so is the unit vector directed along .

Thus we can define a new function,

This new function, , is now a function of three-variables, each of which has periodicity , , and respectively:

This enables us to build up a set of Fourier coefficients, each being indexed by three independent integers . In what follows, we use function notation to denote these coefficients, where previously we used subscripts. If we write a series for on the interval for , we can define the following:

And then we can write:

Further defining:

We can write once again as:

Finally applying the same for the third coordinate, we define:

We write as:

Re-arranging:

Now, every reciprocal lattice vector can be written (but does not mean that it is the only way of writing) as , where are integers and are reciprocal lattice vectors to satisfy ( for , and for ). Then for any arbitrary reciprocal lattice vector and arbitrary position vector in the original Bravais lattice space, their scalar product is:

So it is clear that in our expansion of , the sum is actually over reciprocal lattice vectors:

where

Assuming we can solve this system of three linear equations for , , and in terms of , and in order to calculate the volume element in the original rectangular coordinate system. Once we have , , and in terms of , and , we can calculate the Jacobian determinant: which after some calculation and applying some non-trivial cross-product identities can be shown to be equal to:

(it may be advantageous for the sake of simplifying calculations, to work in such a rectangular coordinate system, in which it just so happens that is parallel to the x axis, lies in the xy-plane, and has components of all three axes). The denominator is exactly the volume of the primitive unit cell which is enclosed by the three primitive-vectors , and . In particular, we now know that

We can write now as an integral with the traditional coordinate system over the volume of the primitive cell, instead of with the , and variables: writing for the volume element ; and where is the primitive unit cell, thus, is the volume of the primitive unit cell.

Hilbert space

As the trigonometric series is a special class of orthogonal system, Fourier series can naturally be defined in the context of Hilbert spaces. For example, the space of square-integrable functions on forms the Hilbert space . Its inner product, defined for any two elements and , is given by: This space is equipped with the orthonormal basis . Then the (generalized) Fourier series expansion of , given by can be written asTemplate:Sfn

The sine-cosine form follows in a similar fashion. Indeed, the sines and cosines form an orthogonal set: (where δmn is the Kronecker delta), and Hence, the set also forms an orthonormal basis for . The density of their span is a consequence of the Stone–Weierstrass theorem, but follows also from the properties of classical kernels like the Fejér kernel.

Fourier theorem proving convergence of Fourier series

In engineering, the Fourier series is generally assumed to converge except at jump discontinuities since the functions encountered in engineering are usually better-behaved than those in other disciplines. In particular, if is continuous and the derivative of (which may not exist everywhere) is square integrable, then the Fourier series of converges absolutely and uniformly to .[21] If a function is square-integrable on the interval , then the Fourier series converges to the function almost everywhere. It is possible to define Fourier coefficients for more general functions or distributions, in which case pointwise convergence often fails, and convergence in norm or weak convergence is usually studied.

-

Four partial sums (Fourier series) of lengths 1, 2, 3, and 4 terms, showing how the approximation to a square wave improves as the number of terms increases (animation)

-

Four partial sums (Fourier series) of lengths 1, 2, 3, and 4 terms, showing how the approximation to a sawtooth wave improves as the number of terms increases (animation)

-

Example of convergence to a somewhat arbitrary function. Note the development of the "ringing" (Gibbs phenomenon) at the transitions to/from the vertical sections.

The theorems proving that a Fourier series is a valid representation of any periodic function (that satisfies the Dirichlet conditions), and informal variations of them that don't specify the convergence conditions, are sometimes referred to generically as Fourier's theorem or the Fourier theorem.[22][23][24][25]

Least squares property

The earlier Template:EquationNote:

is a trigonometric polynomial of degree that can be generally expressed as:

Parseval's theorem implies that:

Convergence theorems

Template:See also Because of the least squares property, and because of the completeness of the Fourier basis, we obtain an elementary convergence result.

Template:Math theorem If is continuously differentiable, then is the Fourier coefficient of the first derivative . Since is continuous, and therefore bounded, it is square-integrable and its Fourier coefficients are square-summable. Then, by the Cauchy–Schwarz inequality,

This means that is absolutely summable. The sum of this series is a continuous function, equal to , since the Fourier series converges in to :

This result can be proven easily if is further assumed to be , since in that case tends to zero as . More generally, the Fourier series is absolutely summable, thus converges uniformly to , provided that satisfies a Hölder condition of order . In the absolutely summable case, the inequality:

proves uniform convergence.

Many other results concerning the convergence of Fourier series are known, ranging from the moderately simple result that the series converges at if is differentiable at , to more sophisticated results such as Carleson's theorem which states that the Fourier series of an function converges almost everywhere.

Divergence

Since Fourier series have such good convergence properties, many are often surprised by some of the negative results. For example, the Fourier series of a continuous T-periodic function need not converge pointwise. The uniform boundedness principle yields a simple non-constructive proof of this fact.

In 1922, Andrey Kolmogorov published an article titled Une série de Fourier-Lebesgue divergente presque partout in which he gave an example of a Lebesgue-integrable function whose Fourier series diverges almost everywhere. He later constructed an example of an integrable function whose Fourier series diverges everywhere.Template:Sfn

It is possible to give explicit examples of a continuous function whose Fourier series diverges at 0: for instance, the even and 2π-periodic function f defined for all x in [0,π] by[26]

Because the function is even the Fourier series contains only cosines:

The coefficients are:

As Template:Mvar increases, the coefficients will be positive and increasing until they reach a value of about at for some Template:Mvar and then become negative (starting with a value around ) and getting smaller, before starting a new such wave. At the Fourier series is simply the running sum of and this builds up to around

in the Template:Mvarth wave before returning to around zero, showing that the series does not converge at zero but reaches higher and higher peaks. Note that though the function is continuous, it is not differentiable.

See also

- ATS theorem

- Carleson's theorem

- Dirichlet kernel

- Discrete Fourier transform

- Fast Fourier transform

- Fejér's theorem

- Fourier analysis

- Fourier inversion theorem

- Fourier sine and cosine series

- Fourier transform

- Gibbs phenomenon

- Half range Fourier series

- Laurent series – the substitution q = eix transforms a Fourier series into a Laurent series, or conversely. This is used in the q-series expansion of the j-invariant.

- Least-squares spectral analysis

- Multidimensional transform

- Residue theorem integrals of f(z), singularities, poles

- Sine and cosine transforms

- Spectral theory

- Sturm–Liouville theory

- Trigonometric moment problem

Notes

References

Bibliography

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book 2003 unabridged republication of the 1878 English translation by Alexander Freeman of Fourier's work Théorie Analytique de la Chaleur, originally published in 1822.

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book Translated by M. Ackerman from Vorlesungen über die Entwicklung der Mathematik im 19 Jahrhundert, Springer, Berlin, 1928.

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book The first edition was published in 1935.

External links

Template:PlanetMath attribution Template:Series (mathematics) Template:Authority control

- ↑ Template:Dictionary.com

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namediit.edu - ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Wilhelm Flügge, Stresses in Shells (1973) 2nd edition. Template:Isbn. Originally published in German as Statik und Dynamik der Schalen (1937).

- ↑ Template:Cite book Template:Pb Whilst the cited article does list the author as Fourier, a footnote on page 215 indicates that the article was actually written by Poisson and that it is, "for reasons of historical interest", presented as though it were Fourier's original memoire.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Vanishing of Half the Fourier Coefficients in Staggered Arrays

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book