Snellius–Pothenot problem

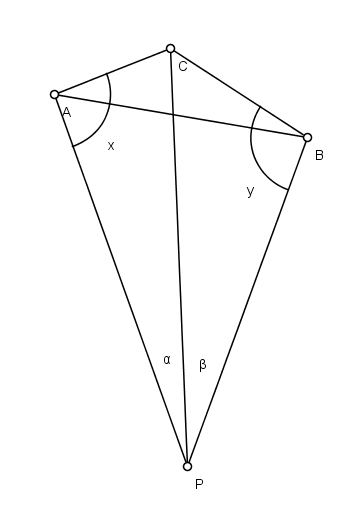

In trigonometry, the Snellius–Pothenot problem is a problem first described in the context of planar surveying. Given three known points Template:Mvar, an observer at an unknown point Template:Mvar observes that the line segment Template:Overline subtends an angle Template:Mvar and the segment Template:Overline subtends an angle Template:Mvar; the problem is to determine the position of the point Template:Mvar. (See figure; the point denoted Template:Mvar is between Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar as seen from Template:Mvar).

Since it involves the observation of known points from an unknown point, the problem is an example of resection. Historically it was first studied by Snellius, who found a solution around 1615.

Formulating the equations

First equation

Denoting the (unknown) angles Template:Math as Template:Mvar and Template:Math as Template:Mvar gives:

by using the sum of the angles formula for the quadrilateral Template:Mvar. The variable Template:Mvar represents the (known) internal angle in this quadrilateral at point Template:Mvar. (Note that in the case where the points Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar are on the same side of the line Template:Mvar, the angle Template:Math will be greater than Template:Pi).

Second equation

Applying the law of sines in triangles Template:Math and Template:Math, we can express Template:Overline in two different ways:

A useful trick at this point is to define an auxiliary angle Template:Mvar such that

(A minor note: one should be concerned about division by zero, but consider that the problem is symmetric, so if one of the two given angles is zero one can, if needed, rename that angle Template:Mvar and call the other (non-zero) angle Template:Mvar, reversing the roles of Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar as well. This will suffice to guarantee that the ratio above is well defined. An alternative approach to the zero angle problem is given in the algorithm below.)

With this substitution the equation becomes

Now two known trigonometric identities can be used, namely

to put this in the form of the second equation;

Now these two equations in two unknowns must be solved. Once Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar are known the various triangles can be solved straightforwardly to determine the position of Template:Mvar.[1] The detailed procedure is shown below.

Solution algorithm

Given are two lengths Template:Mvar, and three angles Template:Mvar, the solution proceeds as follows.

- calculate where

atan2is a computer function, also called the arctangent of two arguments, that returns the arctangent of the ratio of the two values given. Note that in Microsoft Excel the two arguments are reversed, so the proper syntax would be= atan2(AC*\sin(beta), BC*\sin(alpha)). Theatan2function correctly handles the case where one of the two arguments is zero. - calculate

- calculate

- find

- find

- find (This comes from the law of cosines.)

- find

If the coordinates of and are known in some appropriate Cartesian coordinate system then the coordinates of Template:Mvar can be found as well.

Geometric (graphical) solution

By the inscribed angle theorem the locus of points from which Template:Overline subtends an angle Template:Mvar is a circle having its center on the midline of Template:Overline; from the center Template:Mvar of this circle, Template:Overline subtends an angle Template:Math. Similarly the locus of points from which Template:Overline subtends an angle Template:Mvar is another circle. The desired point Template:Mvar is at the intersection of these two loci.

Therefore, on a map or nautical chart showing the points Template:Mvar, the following graphical construction can be used:

- Draw the segment Template:Overline, the midpoint Template:Mvar and the midline, which crosses Template:Overline perpendicularly at Template:Mvar. On this line find the point Template:Mvar such that Draw the circle with center at Template:Mvar passing through Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar.

- Repeat the same construction with points Template:Mvar and the angle Template:Mvar.

- Mark Template:Mvar at the intersection of the two circles (the two circles intersect at two points; one intersection point is Template:Mvar and the other is the desired point Template:Mvar.)

This method of solution is sometimes called Cassini's method.

Rational trigonometry approach

The following solution is based upon a paper by N. J. Wildberger.[2] It has the advantage that it is almost purely algebraic. The only place trigonometry is used is in converting the angles to spreads. There is only one square root required.

- define the following:

- now let:

- the following equation gives two possible values for Template:Math:

- choosing the larger of these values, let:

finally:

Solution via Geometric Algebra

Ventura et al. [3] solve the planar and three-dimensional Snellius-Pothenot problem via Vector Geometric Algebra and Conformal Geometric Algebra. The authors also characterize the solutions' sensitivity to measurement errors.

The indeterminate case

When the point Template:Mvar happens to be located on the same circle as Template:Mvar, the problem has an infinite number of solutions; the reason is that from any other point Template:Mvar located on the arc Template:Overarc of this circle the observer sees the same angles Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar as from Template:Mvar (inscribed angle theorem). Thus the solution in this case is not uniquely determined.

The circle through Template:Mvar is known as the "danger circle", and observations made on (or very close to) this circle should be avoided. It is helpful to plot this circle on a map before making the observations.

A theorem on cyclic quadrilaterals is helpful in detecting the indeterminate situation. The quadrilateral Template:Mvar is cyclic iff a pair of opposite angles (such as the angle at P and the angle at Template:Mvar) are supplementary i.e. iff . If this condition is observed the computer/spreadsheet calculations should be stopped and an error message ("indeterminate case") returned.

Solved examples

(Adapted form Bowser,[4] exercise 140, page 203). Template:Mvar are three objects such that Template:Overline = 435 (yards), Template:Overline = 320, and Template:Math = 255.8 degrees. From a station Template:Mvar it is observed that Template:Math = 30 degrees and Template:Math = 15 degrees. Find the distances of Template:Mvar from Template:Mvar. (Note that in this case the points Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar are on the same side of the line Template:Mvar, a different configuration from the one shown in the figure).

Answer: Template:Overline = 790, Template:Overline = 777, Template:Overline = 502.

A slightly more challenging test case for a computer program uses the same data but this time with Template:Math = 0. The program should return the answers 843, 1157 and 837.

Naming controversy

The British authority on geodesy, George Tyrrell McCaw (1870–1942) wrote that the proper term in English was Snellius problem, while Snellius-Pothenot was the continental European usage.[5]

McCaw thought the name of Laurent Pothenot (1650–1732) did not deserve to be included as he had made no original contribution, but merely restated Snellius 75 years later.

See also

Notes

- Gerhard Heindl: Analysing Willerding’s formula for solving the planar three point resection problem, Journal of Applied Geodesy, Band 13, Heft 1, Seiten 27–31, ISSN (Online) 1862-9024, ISSN (Print) 1862-9016, DOI: [1]

References

- Edward A. Bowser: A treatise on plane and spherical trigonometry, Washington D.C., Heath & Co., 1892, page 188 Google books

- ↑ Bowser: A treatise

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Bowser: A treatise

- ↑ Template:Cite journal