Sikidy

Template:Short description Template:Italic title

SikidyTemplate:Efn is a form of algebraic geomancy practiced by Malagasy peoples in Madagascar. It involves algorithmic operations performed on random data generated from tree seeds, which are ritually arranged in a tableau called a Template:Lang and divinely interpreted after being mathematically operated on. Columns of seeds, designated "slaves" or "princes" belonging to respective "lands" for each, interact symbolically to express Template:Lang ('fate') in the interpretation of the diviner. The diviner also prescribes solutions to problems and ways to avoid fated misfortune, often involving a sacrifice.[1]

The centuries-old practice derives from Islamic influence brought to the island by medieval Arab traders. The Template:Lang is consulted for a range of divinatory questions pertaining to fate and the future, including identifying sources of and rectifying misfortune, reading the fate of newborns, and planning annual migrations. The mathematics of Template:Lang include the concepts of Boolean algebra, symbolic logic and parity.

History

The practice is several centuries old, and is influenced by Arab geomantic traditions of Arab Muslim traders on the island.[1][2] Stephen Ellis and Solofo Randrianja describe Template:Lang as "probably one of the oldest components of Malagasy culture", writing that it most likely the product of an indigenous divinatory art later influenced by Islamic practice.[3] Umar H. D. Danfulani writes that the integration of Arabic divination into indigenous divination is "clearly demonstrated" in Madagascar, where the Arabic astrological system was adapted to the indigenous agricultural system and meshed with Malagasy lunar months by "adapting indigenous months, Template:Lang, to the astrological months, Template:Lang".[4] Danfulani also describes the concepts in Template:Lang of "houses" (lands) and "kings in their houses" as retained from medieval Arabic astrology.[4]

Most writers link the practice to the "sea-going trade involving the southwest coast of India, the Persian Gulf, and the east coast of Africa in the 9th or 10th century C.E."[1] Though the etymology of Template:Lang is unknown, it has been posited that the word derives from the Arabic sichr ('incantation' or 'charm'). Template:Lang was of central importance to pre-Christian Malagasy religion, with one practitioner quoted in 1892 as calling Template:Lang "the Bible of our ancestors".[2] A missionary report from 1616 describes one form of Template:Lang using tamarind seeds,[5] and another using fingered markings in the sand.[1] The early colonial French governor of Madagascar Étienne de Flacourt documented Template:Lang in the mid-17th century:[2]

The "infiltration" of Malagasy kingdoms by Antemoro diviners, and Matitanana's role as a place for astrological and divinatory learning, help to explain the relatively uniform practicing of Template:Lang across Madagascar.[4]

Origin myths

Mythic tradition relating to the origin of Template:Lang "links [the practice] both to the return by walking on water of Arab ancestors who had intermarried with Malagasy but then left, and to the names of the days of the week"[1] and holds that the art was supernaturally communicated to the ancestors, with Zanahary (the supreme deity of Malagasy religion) giving it to Ranakandriana, who then gave it to a line of diviners (Ranakandriana to Ramanitralanana to Rabibi-andrano to Andriambavi-maitso (who was a woman) to Andriam-bavi-nosy), the last of whom terminated the monopoly by giving it to the people, declaring: "Behold, I give you the Template:Lang, of which you may inquire what offerings you should present in order to obtain blessings; and what expiation you should make so as to avert evils, when any are ill or under apprehension of some future calamity".[2][6]

A mythic anecdote of Ranakandriana says that two men observed him one day playing in the sand. In fact he was practicing a form of Template:Lang worked in sand called Template:Lang. The two men seized him, and Ranakandriana promised that he would teach them something if they released him. They agreed, and Ranakandriana taught them in depth how to work the Template:Lang. The two men then went to their chief and told him that they could tell him "the past and the future—what was good and what was bad—what increased and what diminished." The chief asked them to tell him how he could obtain plenty of cattle. The two men worked their Template:Lang and told the chief to kill all of his bulls, and that "great numbers would come to him" on the following Friday. The chieftain, doubting, asked what would happen if their prediction didn't come true, and the two men promised they would pay with their lives. The chief agreed and killed his bulls. On Thursday, thinking he'd been duped, he prematurely killed the first man of the two who'd told him about the divinatory art. On Friday, however, "vast herds" came amidst heavy rain, actually filling an immense plain in their crowd. The chieftain lamented the Template:Lang's wrongful execution and ordered for him a pompous funeral. The chieftain took the second man as his close adviser and friend, and trusted the Template:Lang forever afterwards.[6] The British missionary William Ellis recorded in 1839 two idiomatic expressions used in Madagascar that come from this story: "Tsy mahandry andro Zoma" (Template:Lit) is said of someone extremely impatient, and heavy rainshowers falling in rapid succession are called "sese omby" (Template:Lit).[6]

Rites and practitioners

The divination is performed by a practitioner called an Template:Lang, Template:Lang (Template:Lit),Template:Efn Template:Lang, or Template:Lang (derived from the Arabic anbia, meaning 'prophet')[2] who guides the client through the process and interprets the results in the context of the client's inquiries and desires.[7][1] As part of an Template:Lang's formal initiation into the art, which includes a long period of apprenticeship, the initiate must gather 124 and 200 Template:Lang (Entada sp.) or Template:Lang (tamarind) tree seeds for his subsequent ritual use in Template:Lang.[8]

Template:Ill writes that, at least among the Sakalava, a man must be 40 years old before learning and practicing Template:Lang, or he risks death. Before beginning to study, a student practitioner must make incisions at the tips of his index finger, his middle finger, and his tongue, and put within the incisions a paste containing red pepper and crushed wasp. This paste impregnates the fingers that will move the seeds of the Template:Lang and the tongue that will speak their revelations with the power to decipher the Template:Lang. Once this is done, he leaves at dawn to search for a Template:Lang (Entada chrysostachys) tree. Upon finding it, he throws his spear at its branches, shaking the tree and causing its large seed pods to fall. During this act, some Template:Lang say: "When you were on the steep peak and in the dense forest, on you the crabs climbed, from you the crocodiles made their bed, with their paws the birds trod on you. Whether you are suspended in the trees or buried, you are never dried up nor rotten." In 1970, Decary reported that the salary paid by an apprentice to his master is "not very high": up to five francs, plus a red rooster's feather.[5]

Some Template:Lang are considered specialists, dealing only with areas of inquiry and resolution within their expertise.[1] In the process of divination, the Template:Lang relates interactively to the client, asking new questions and discussing the interpretation of the seeds.[7] Alfred Grandidier estimated in the late 19th century that roughly one in three Malagasy people had a firm grasp on the art; by 1970 Raymond Decary wrote that the number of Template:Lang was now more limited, and the common knowledge of how to operate and read the Template:Lang was now more basic, with masters of Template:Lang becoming more rare.[5]

Template:Lang also provide guidance on how to avoid the misfortune divined in the subject's fate. Solutions include offerings, sacrifices, charms (called Template:Lang), stored remedies, or observed Template:Lang (taboos).[9] The resolution often comes in the form of the ritual disposal of a symbolic object of misfortune, called the Template:Lang:Template:Efn for example, if the Template:Lang predicts the death of two men, then two locusts should be killed and thrown away as the Template:Lang.[10] William Ellis compares this practice to the ancient Jewish scapegoat.[6] Other Template:Lang objects can be trivial, such as "a little grass", some earth, or the water with which the patient rinses his mouth. If the Template:Lang is ashes, they are blown from the hand to be carried off by the wind; if it is cut money, it is thrown to the bottom of deep waters; if a sheep, it is "carried away to a distance on the shoulders of a man, who runs with all his might, mumbling as he goes, as if in the greatest rage against the Template:Lang, for the evils it is bearing away." If it is a pumpkin, it is carried away a short distance and then thrown on the ground with fury and indignation.[6] The disposal of a Template:Lang may be as simple as a man standing at his doorway, throwing the object a few feet away, and saying the word "Template:Lang".[6] Ellis reports the following Template:Lang for various sources and manifestations of evil:[6]

| Evil's origin | Template:Lang |

|---|---|

| Heaven | An herb called Template:Lang (Portulaca oleracea) |

| The earth | A water-flower |

| Cattle | A grasshopper called Template:Lang |

| Sheep | A small fish called Template:Lang, Template:Lit |

| Money | A grasshopper called Template:Lang |

| The mouth; speaking | The mouth or brim of a small basket |

| The north | A tree called Template:Lang, Template:Lit |

| The south | An herb called Template:Lang |

| The west | A rush called Template:Lang |

| The east | An herb called Template:Lang |

| Fire | A red flower called Template:Lang (Euphorbia splendens) |

| Template:Lang (the reproach or blame of parents or friends) | A broken fragment of the Template:Lang (water vessel) |

| Foretold danger or misfortune | Template:Lang |

|---|---|

| Sickness | A piece of a tree that has been injured by accident, cutting, or maiming (Template:Lang, Template:Lit) |

| Death | An object without life; or a piece of a stone, especially granite, in incipient degradation (Template:Lang, Template:Lit) |

| Partial danger of witchcraft (some person's partial inclination to bewitch the offerer) | The kernel or gland in a bullock's fat, called the Template:Lang, Template:Lit |

| Danger from persons collecting together (foretells burial) | A grass called Template:Lang or Template:Lang, together with some earth, thrown away from a point measured eight to ten feet away |

A divine offering, called a Template:Lang, is also prescribed by the Template:Lang. The Template:Lang may consist of a combination of beads, silver chains, ornaments, meats, herbs, and the singing of a child. Other Template:Lang objects include "a young bullock which just begins to bellow and to tear up the earth with his horns", fowl, rice mixed with milk and honey, a plantain tree flush with fruit, "slime from frogs floating on the water", and a groundnut called Template:Lang. Template:Lang amulets and bracelets may continue to be worn after the cause of their prescription, effectively becoming Template:Lang.[6]

Recovery without adherence to divined prescription and Template:Lang is believed "almost impossible". William Ellis recorded in 1838 that, though the application of indigenous remedies was most common, some patients had lately been instructed as part of the Template:Lang resolution to ask the local foreign missionaries for medicine.[6]

Occasions and questions for Template:Lang

Problems and questions for divined resolution via Template:Lang include the selection of a day on which to do something (including taking a trip, planting, a wedding,[6] and the exhumation of ancestral corpses), whether a newborn child's destiny is compatible with its parents and thus whether it ought to be cared for by another family, the finding of a spouse, the finding of lost objects, the identification of a thief, and the explanation for a misfortune, including illness or sterility.[1]

Raymond Decary writes that the Template:Lang is consulted "in all circumstances", but especially:

- In cases of illness, which are understood to be either punishments or warnings from supernatural powers due to the transgression of a Template:Lang (taboo), or poisonings or curses (called Template:Lang) from other humans.

- Before undertaking a journey, in order to divine an auspicious day for travel.

- To acquire wealth or foresee the growth of herds (gold prospecting and panning must take place on a day selected by the Template:Lang).

- For all questions relating to women, including whether a potential bride has a fate aligned with her suitor's.

- In order to cast a bad spell on someone.

- To search for or track down thieves.[5]

The kind and color of sheep to be sacrificed in a wedding procession is also divined by Template:Lang.[6] Among the forest-dwelling Mikea people, Template:Lang is used "to direct the timing of residential movements to the forest (Template:Lang)".[11]

William Ellis describes two ritual occasions for Template:Lang relating to infants: the declaring of the child's destiny, and the "scrambling" ceremony.[6]

As one of the "first acts" following a child's birth, the child's father or close relative consults the local Template:Lang, who works the Template:Lang in order to read the child's destiny. When a child's destiny is declared to be favorable, "the child is nurtured with that tenderness and affection which nature inspires, and the warmest gratulations are tendered by the friends of the parents."[6]

The "scrambling" ceremony, which only occurs with firstborn infants, takes place two or three months after the child's birth on a day divined by the Template:Lang to be lucky or good. The child's friends and family gather, and the child's mother is decorated with silver chains on her head. If the infant is a boy, the father carries him, along with some ripe bananas, on his back. In a rice pan, a mixture is cooked, consisting of the fat from a zebu ox's hump, rice, milk, honey, and a grass called Template:Lang. One lock, called the Template:Lang ('evil lock') is cut from the left side of the child's head and thrown away, "in order to avert calamity". A second lock, called the Template:Lang ('the fortunate lock'), is cut from the right side, and added to the mixture in the rice pan. The mélange is mixed well and held up in its pan by the youngest girl of the family, at which point the gathered (especially the women) make a rush for its contents. It is believed that those who obtain a portion of the mixture are bound to become mothers. The scramble also takes place with bananas, lemons, and sugarcane. The rice pan is then considered sacred, and cannot be removed from the house for three days, "otherwise the virtue of those observances is supposed to be lost".[6]

Incantation

To "awaken" the seeds in his bag as well as his own verbal powers, the Template:Lang incants to the gods or earth spirits in attempt to constrain the gods/spirits to tell the truth, with emphasis on "the trickiness of the communicating entities, who misle[a]d if they [can]", and orates the practice's origin myth.[1] As he incants, the Template:Lang turns the seeds on a mat eastward[5] with his right hand.[2] One Merina incantation[5] quoted by Norwegian missionary Lars Dahle reads:[2]

Template:BlockquoteWhen practicing the Template:Lang, Sakalava diviners work with a fragment of hyaline quartz in front of their seeds, which is set out before the seeds are produced from their sack.[5]

Arranging the seeds

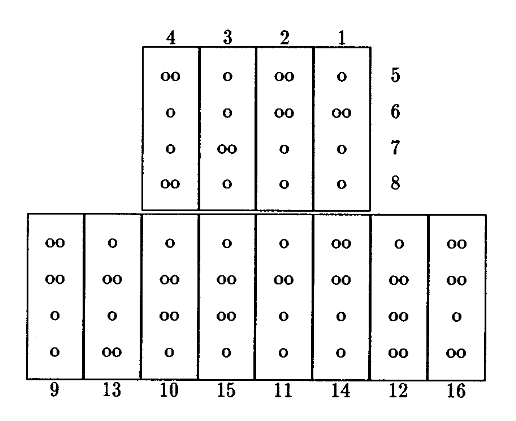

After his incantation, the Template:Lang takes a fistful of awakened seeds from his bag and randomly divides the seeds into four piles. Seeds are removed two at a time from each pile until there is either one seed or two seeds remaining in each. The four remaining "piles" (now either single seeds or pairs) become the first entries in the first column of a Template:Lang (tableau). The process is repeated three more times, with each new column of seeds being placed on the Template:Lang to the left of the previous. At the end of this, the array consists of four randomly-generated columns of four values (each being either one seed or two) each. The generated data represented in this array is called the Template:Lang (Template:Lit). There are 65,536 possible Template:Lang arrays.Template:Efn From the Template:Lang data, four additional "columns" are read as the rows across the Template:Lang's columns, and eight additional columns are generated algorithmically and placed in a specific order below the four original columns.[1]

Algorithmically-generated columns

Columns 9–16 of the Template:Lang are generated using the XOR logical operation (), which determines a value based on whether two other values are the same or different. In Template:Lang, the XOR operation is used to compare values in sequence across two existing columns and generate corresponding values for a third column: two seeds if the corresponding values are identical across the pair, and one seed if the values are different. The rules for generating a column from the XOR operation are (with o representing one seed, and oo representing two):[1]

The first 12 columns are generated algorithmically from pairs of adjacent columns in the randomly-generated Template:Lang (the four-by-four grid of seeds representing eight datasets across its four columns and four rows). The last four columns (12–16) of the Template:Lang are derived from the algorithmically-generated columns, with column 16 operating on the first and fifteenth column as a pair.[1]

For example, the first value of column 9 is determined by comparing the first values of columns 7 and 8. If they are the same (both one seed or both two seeds), the first value of column 9 will be two seeds. If they are different, the first value of column 9 will be one seed. This operation iterates for each pair of corresponding values in columns 7 and 8, creating a complete set of values for column 9. Column 10 is then generated by applying the XOR operation between the values in columns 5 and 6. Similarly, column 11 is generated from columns 3 and 4, and column 12 from columns 1 and 2.[1][2]

Columns 13-16 are generated in the same manner, performing the XOR operation on ascending pairs of the algorithmically-generated columns, starting with columns 9 and 10 (to generate column 13) and ending with columns 15 and 1 (to generate column 16).[1]

Checks

Template:See also The Template:Lang performs three algorithmic and logical checks to verify the Template:Lang's validity according to its generative logic: one examining the whole Template:Lang, one examining the results of combining some particular columns, and one parity check examining only one column.[1] First, the Template:Lang checks that at least two columns in the Template:Lang are identical. Next, it is ensured that the pairs of columns 13 and 16, 14 and 1, and 11 and 2 (called "the three inseparables"Template:Efn) all yield the same result when combined via the XOR operation. Finally, it is checked that there is an even number of seeds in the 15th column—the only column for which parity is logically certain.[1]

Each of these three checks are mathematically proven valid in a 1997 paper by American ethnomathematician Marcia Ascher.[1] Verification through the use of Microsoft Excel was achieved and published by Gomez et al. in 2015.[12]

Divination

Once the Template:Lang has checked the Template:Lang, his analysis and divination can begin. Certain questions and answers rely on additional columns beyond the prepared sixteen. Some of these columns are read spatially in patterns across the existing Template:Lang's data, and some are generated with additional XOR operations referring to pairs of columns within the secondary series. These new columns can involve "about 100 additional algorithms".[1]

Each column making up the Template:Lang has a distinct divine referent:[1][13]

| Column number | Malagasy name | Symbolic meaning | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Template:Lang | The client or patient | From Arabic طلع Template:Transliteration, meaning 'to rise'. |

| 2 | Template:Lang or Template:Lang | Material goods; riches; zebu | From Arabic المال Template:Transliteration, meaning 'goodness', 'richness', 'property'. |

| 3 | Template:Lang | A male evil-doer (Template:Lit) | |

| 4 | Template:Lang | The domicile; the country; the Earth | From Arabic بلد Template:Transliteration, meaning 'country' or 'land'. |

| 5 | Template:Lang | The fifth child; descendants; children; youth | |

| 6 | Template:Lang or Template:Lang | Slaves | From Arabic عبد Template:Transliteration, meaning 'slaves'. |

| 7 | Template:Lang, Template:Lang, or Template:Lang | The wife of the house | From Arabic بيت Template:Transliteration, meaning 'house', and النساء Template:Transliteration, meaning 'wife'. |

| 8 | Template:Lang | The sorcerer; illness; the enemy (Template:Lit) | |

| 9 | Template:Lang | The spirits (Template:Lit) | |

| 10 | Template:Lang or Template:Lang | Nourishment; the healing diviner | From Arabic محسن Template:Transliteration or Template:Transliteration, meaning 'the beneficient' and 'the generous' |

| 11 | Template:Lang | Everything that can be eaten | |

| 12 | Template:Lang | The Creator | |

| 13 | Template:Lang or Template:Lang | The chiefs and elders | |

| 14 | Template:Lang or Template:Lang | The road | |

| 15 | Template:Lang or Template:Lang | The road | |

| 16 | Template:Lang | The house or its inhabitants |

There are sixteen possible configurations of Template:Lang seeds in each column of four values. These formations are known to the diviner and identified with names, which vary regionally. Some names relate to names of months. For many Template:Lang, the formations are associated with directions.Template:Efn[1] The eight formations with an even number of seeds are designated as "princes", while the eight with an odd number of seeds are "slaves". Each slave and prince has its place in a square whose sides are associated with the four cardinal directions. The square is divided into a northwestern "Land of Slaves" and a southeastern "Land of Princes" by a diagonal line extending from its northeastern corner to its southeastern corner. Despite their names, each "Land" contains both slaves and princes, including one migrating prince and one migrating slave that move directionally with the sun, such that the migrators belong to different lands depending on the time of day at which the Template:Lang is performed. The migrators are in the east from sunrise to 10 AM, in the north from 10 AM to 3 PM, and in the west from 3 PM to sunset. Template:Lang is never performed at night, and thus the migrators are never in the south.[1]Template:Efn

The power to see into the past or future is greater in Template:Lang in which all four directions are represented, and most powerful in Template:Lang with four directions represented but with one direction having only one representative. These Template:Lang are called Template:Lang ('Template:Lang-unique'). Beyond being powerful arrangements for divination, Template:Lang represent a particular abstract interest to Template:Lang, who seek to understand them and the data which generate them as an unsolved intellectual challenge. Knowing many Template:Lang leads to personal prestige for the Template:Lang, with discovered examples being posted on doors and spread among diviners by word of mouth.[1]

Divination of the Template:Lang refer to hierarchies of power relating to position and class of figures. "Princes are more powerful than slaves; figures from the Land of Princes are more powerful than those from the Land of Slaves; slaves from the same land are never harmful to one another; and battles between two princes from the Land of Princes are always serious but never end in death."[1]

In divinations relating to illness, the client and creator columns being the same indicates that there will definitely be recovery; if the client and ancestors columns are the same, the illness is due to some discontent on the part of the ancestors; and if the client and house columns are the same, the illness is the same as one that has previously ended in recovery.[1] The relationship between the client and spirit columns is directly referent to illness. If the client is a slave of the east and the spirit is a prince of the south, the client is dominated by the illness, and thus the illness is divined to be serious—but not fatal, because both the east and the south are in the Land of Princes. If the client is a prince of the north (in the Land of Slaves), and the spirit a prince of the south (in the Land of Princes), there would be a difficult battle with a significant chance of the client dying.[1]

If the ninth and fifteenth columns are the same, a bead must be offered as a Template:Lang, called Template:Lang (Template:Lit). If the first and fourth are the same, then a piece of a tree that grows in the villages (not in the fields) must be offered.[6] If the values of the tenth and fifteenth columns added together and subtracted by two equal the values of the first, a stone (called Template:Lang, Template:Lit) is thrown, retrieved, and carefully preserved by a friend or relation, and so not lost.[6]

The most exceptionally hopeless and severe outcome in a Template:Lang is each value in the first four columns (and thus in the entire tableau) being two seeds. This is called the "red Template:Lang".[1]

A study computer-simulating the algorithmic generation and objective initial interpretation (according to Sakalava tradition) of the 65,536 possible arrangements of Template:Lang found that, assuming a male client and an inquiry about an illness' cause, the divined cause of illness would be sorcery 21.1% of the time, witchcraft 16.5% of the time, Template:LangTemplate:Efn for 9.6%, the village chief for 2.6%, the contamination of food with dirt (which may involve carelessness or evil intentions) for .8%, ancestors for .7%, and undetermined for 48.7%.[14][1]

Figures

The following are the most common names and meanings for the sixteen geomantic figures of the Template:Lang.[9] Names that also refer to lunar months are marked with a '☾'.

| Figure | Malagasy name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Template:Lang | Emaciation; path, road | |

| Template:Lang | Slave; cool speech | |

| Template:Lang ☾ | Child; evil thoughts | |

| Template:Lang | Zanahary; most sacred | |

| Template:Lang | Charm; mourning | |

| Template:Lang | Woman; death | |

| Template:Lang | Earth; auspicious | |

| Template:Lang ☾ | Abundance | |

| Template:Lang ☾ | Money; unhappiness, misfortune | |

| Template:Lang ☾ | Chief or child; tears | |

| Template:Lang | Slave; evil thoughts | |

| Template:Lang | House; food | |

| Template:Lang | Water spirit; joy | |

| Template:Lang | Diviner; crowd, mob; grief, trouble | |

| Template:Lang ☾ | Food; anger, wrath | |

| Template:Lang ☾ | Robbers, rogues; unhappiness, misfortune |

Related traditions

Other Malagasy methods of divination include astrology, cartomancy, ornithomancy, extispicy, and necromantic dream-interpretation.[5]

African sixteen-figure divinatory traditions

Aside from Arabic geomancy, a number of African divination methods using sixteen basic figures have been studied, including Yoruba Ifá cowrie-shell divination, also known by its Fon name Fa and the Ewe and Igbo name Afa. African diasporic populations in Latin America have retained the practice, with the tradition being called Ifa among Afro-Cubans, Afro-Brazilians, and Afro-Haitians. Umar H. D. Danfulani records a breadth of sixteen-figure divinatory traditions across Africa:[4]

- Ifá – from Yoruba culture

- Fa – from Fon culture; same tradition as Ifá

- Afa – from Igbo and Ewe cultures; same tradition as Ifá

- Pa; Pe – from Chadic speakers of the Jos Plateau

- Noko – from Jukun and Kuteb cultures

- Eba – from Ekoi culture

- Agbigba – from Igbira and Okun cultures

- Efa – from Ekoi culture

- Eva – from Isoko culture

- Ominigbon; Ogwega; Iha Ogwega – from Bini (Edo) culture

- Hakata – "from Zaire and Angola to South Africa"; "bone casting/throwing"; originating from the court circles of Mwene Mutapa (present-day Zimbabwe) and "in the southern Congo river-basin empires"

- Template:Lang – from Malagasy culture

See also

References

Notes

Template:NotelistTemplate:Madagascar topicsTemplate:Divination

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 1.24 1.25 1.26 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book Cited from Credo Reference version.

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book