Galois geometry

Galois geometry (named after the 19th-century French mathematician Évariste Galois) is the branch of finite geometry that is concerned with algebraic and analytic geometry over a finite field (or Galois field).[1] More narrowly, a Galois geometry may be defined as a projective space over a finite field.[2]

Objects of study include affine and projective spaces over finite fields and various structures that are contained in them. In particular, arcs, ovals, hyperovals, unitals, blocking sets, ovoids, caps, spreads and all finite analogues of structures found in non-finite geometries. Vector spaces defined over finite fields play a significant role, especially in construction methods.

Projective spaces over finite fields

Notation

Although the generic notation of projective geometry is sometimes used, it is more common to denote projective spaces over finite fields by Template:Math, where Template:Mvar is the "geometric" dimension (see below), and Template:Mvar is the order of the finite field (or Galois field) Template:Math, which must be an integer that is a prime or prime power.

The geometric dimension in the above notation refers to the system whereby lines are 1-dimensional, planes are 2-dimensional, points are 0-dimensional, etc. The modifier, sometimes the term projective instead of geometric is used, is necessary since this concept of dimension differs from the concept used for vector spaces (that is, the number of elements in a basis). Normally having two different concepts with the same name does not cause much difficulty in separate areas due to context, but in this subject both vector spaces and projective spaces play important roles and confusion is highly likely. The vector space concept is at times referred to as the algebraic dimension.[3]

Construction

Let Template:Math denote the vector space of (algebraic) dimension Template:Math defined over the finite field Template:Math. The projective space Template:Math consists of all the positive (algebraic) dimensional vector subspaces of Template:Math. An alternate way to view the construction is to define the points of Template:Math as the equivalence classes of the non-zero vectors of Template:Math under the equivalence relation whereby two vectors are equivalent if one is a scalar multiple of the other. Subspaces are then built up from the points using the definition of linear independence of sets of points.

Subspaces

A vector subspace of algebraic dimension Template:Math of Template:Math is a (projective) subspace of Template:Math of geometric dimension Template:Mvar. The projective subspaces are given common geometric names; points, lines, planes and solids are the 0,1,2 and 3-dimensional subspaces, respectively. The whole space is an Template:Mvar-dimensional subspace and an (Template:Math)-dimensional subspace is called a hyperplane (or prime).

The number of vector subspaces of algebraic dimension Template:Mvar in vector space Template:Math is given by the Gaussian binomial coefficient,

Therefore, the number of Template:Mvar dimensional projective subspaces in Template:Math is given by

Thus, for example, the number of lines (Template:Mvar = 1) in PG(3,2) is

It follows that the total number of points (Template:Mvar = 0) of Template:Math is

This also equals the number of hyperplanes of Template:Mvar.

The number of lines through a point of Template:Mvar can be calculated to be and this is also the number of hyperplanes through a fixed point.[4]

Let Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar be subspaces of the Galois geometry Template:Math. The intersection Template:Math is a subspace of Template:Math, but the set theoretic union may not be. The join of these subspaces, denoted by Template:Math, is the smallest subspace of Template:Math that contains both Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar. The dimensions of the join and intersection of these two subspaces are related by the formula,

Coordinates

Template:Main With respect to a fixed basis, every vector in Template:Math is uniquely represented by an (Template:Math)-tuple of elements of Template:Math. A projective point is an equivalence class of vectors, so there are many different coordinates (of the vectors) that correspond to the same point. However, these are all related to one another since each is a non-zero scalar multiple of the others. This gives rise to the concept of homogeneous coordinates used to represent the points of a projective space.

History

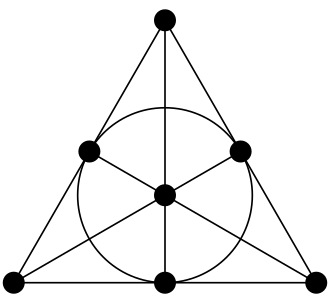

Gino Fano was an early writer in the area of Galois geometries. In his article of 1892,[5] on proving the independence of his set of axioms for projective n-space,[6] among other things, he considered the consequences of having a fourth harmonic point be equal to its conjugate. This leads to a configuration of seven points and seven lines contained in a finite three-dimensional space with 15 points, 35 lines and 15 planes, in which each line contained only three points.[5]Template:Rp All the planes in this space consist of seven points and seven lines and are now known as Fano planes. Fano went on to describe Galois geometries of arbitrary dimension and prime orders.

George Conwell gave an early application of Galois geometry in 1910 when he characterized a solution of Kirkman's schoolgirl problem as a partition of sets of skew lines in PG(3,2), the three-dimensional projective geometry over the Galois field GF(2).[7] Similar to methods of line geometry in space over a field of characteristic 0, Conwell used Plücker coordinates in PG(5,2) and identified the points representing lines in PG(3,2) as those on the Klein quadric.

In 1955 Beniamino Segre characterized the ovals for q odd. Segre's theorem states that in a Galois geometry of odd order (that is, a projective plane defined over a finite field of odd characteristic) every oval is a conic. This result is often credited with establishing Galois geometries as a significant area of research. At the 1958 International Mathematical Congress Segre presented a survey of results in Galois geometry known up to that time.

See also

Notes

References

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite arXiv

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

External links

- Galois geometry at Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, SpringerLink

- ↑ SpringerLink

- ↑ "Projective spaces over a finite field, otherwise known as Galois geometries, ...", Template:Harv

- ↑ There are authors who use the term rank for algebraic dimension. Authors that do this frequently just use dimension when discussing geometric dimension.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ George M. Conwell (1910) "The 3-space PG(3,2) and its Groups", Annals of Mathematics 11:60–76 Template:Doi