Representation theory of the Lorentz group

Template:Short description Template:Good articleTemplate:Use American English

The Lorentz group is a Lie group of symmetries of the spacetime of special relativity. This group can be realized as a collection of matrices, linear transformations, or unitary operators on some Hilbert space; it has a variety of representations.[nb 1] This group is significant because special relativity together with quantum mechanics are the two physical theories that are most thoroughly established,[nb 2] and the conjunction of these two theories is the study of the infinite-dimensional unitary representations of the Lorentz group. These have both historical importance in mainstream physics, as well as connections to more speculative present-day theories.

Development

The full theory of the finite-dimensional representations of the Lie algebra of the Lorentz group is deduced using the general framework of the representation theory of semisimple Lie algebras. The finite-dimensional representations of the connected component of the full Lorentz group Template:Math are obtained by employing the Lie correspondence and the matrix exponential. The full finite-dimensional representation theory of the universal covering group (and also the spin group, a double cover) of is obtained, and explicitly given in terms of action on a function space in representations of and . The representatives of time reversal and space inversion are given in space inversion and time reversal, completing the finite-dimensional theory for the full Lorentz group. The general properties of the (m, n) representations are outlined. Action on function spaces is considered, with the action on spherical harmonics and the Riemann P-functions appearing as examples. The infinite-dimensional case of irreducible unitary representations are realized for the principal series and the complementary series. Finally, the Plancherel formula for is given, and representations of Template:Math are classified and realized for Lie algebras.

The development of the representation theory has historically followed the development of the more general theory of representation theory of semisimple groups, largely due to Élie Cartan and Hermann Weyl, but the Lorentz group has also received special attention due to its importance in physics. Notable contributors are physicist E. P. Wigner and mathematician Valentine Bargmann with their Bargmann–Wigner program,[1] one conclusion of which is, roughly, a classification of all unitary representations of the inhomogeneous Lorentz group amounts to a classification of all possible relativistic wave equations.[2] The classification of the irreducible infinite-dimensional representations of the Lorentz group was established by Paul Dirac's doctoral student in theoretical physics, Harish-Chandra, later turned mathematician,[nb 3] in 1947. The corresponding classification for was published independently by Bargmann and Israel Gelfand together with Mark Naimark in the same year.

Applications

Many of the representations, both finite-dimensional and infinite-dimensional, are important in theoretical physics. Representations appear in the description of fields in classical field theory, most importantly the electromagnetic field, and of particles in relativistic quantum mechanics, as well as of both particles and quantum fields in quantum field theory and of various objects in string theory and beyond. The representation theory also provides the theoretical ground for the concept of spin. The theory enters into general relativity in the sense that in small enough regions of spacetime, physics is that of special relativity.[3]

The finite-dimensional irreducible non-unitary representations together with the irreducible infinite-dimensional unitary representations of the inhomogeneous Lorentz group, the Poincare group, are the representations that have direct physical relevance.[4][5]

Infinite-dimensional unitary representations of the Lorentz group appear by restriction of the irreducible infinite-dimensional unitary representations of the Poincaré group acting on the Hilbert spaces of relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum field theory. But these are also of mathematical interest and of potential direct physical relevance in other roles than that of a mere restriction.[6] There were speculative theories,[7][8] (tensors and spinors have infinite counterparts in the expansors of Dirac and the expinors of Harish-Chandra) consistent with relativity and quantum mechanics, but they have found no proven physical application. Modern speculative theories potentially have similar ingredients per below.

Classical field theory

While the electromagnetic field together with the gravitational field are the only classical fields providing accurate descriptions of nature, other types of classical fields are important too. In the approach to quantum field theory (QFT) referred to as second quantization, the starting point is one or more classical fields, where e.g. the wave functions solving the Dirac equation are considered as classical fields prior to (second) quantization.[9] While second quantization and the Lagrangian formalism associated with it is not a fundamental aspect of QFT,[10] it is the case that so far all quantum field theories can be approached this way, including the standard model.[11] In these cases, there are classical versions of the field equations following from the Euler–Lagrange equations derived from the Lagrangian using the principle of least action. These field equations must be relativistically invariant, and their solutions (which will qualify as relativistic wave functions according to the definition below) must transform under some representation of the Lorentz group.

The action of the Lorentz group on the space of field configurations (a field configuration is the spacetime history of a particular solution, e.g. the electromagnetic field in all of space over all time is one field configuration) resembles the action on the Hilbert spaces of quantum mechanics, except that the commutator brackets are replaced by field theoretical Poisson brackets.[9]

Relativistic quantum mechanics

For the present purposes the following definition is made:[12] A relativistic wave function is a set of Template:Mvar functions Template:Math on spacetime which transforms under an arbitrary proper Lorentz transformation Template:Math as

where Template:Math is an Template:Math-dimensional matrix representative of Template:Math belonging to some direct sum of the Template:Math representations to be introduced below.

The most useful relativistic quantum mechanics one-particle theories (there are no fully consistent such theories) are the Klein–Gordon equation[13] and the Dirac equation[14] in their original setting. They are relativistically invariant and their solutions transform under the Lorentz group as Lorentz scalars (Template:Math) and bispinors (Template:Math) respectively. The electromagnetic field is a relativistic wave function according to this definition, transforming under Template:Math.[15]

The infinite-dimensional representations may be used in the analysis of scattering.[16]

Quantum field theory

In quantum field theory, the demand for relativistic invariance enters, among other ways in that the S-matrix necessarily must be Poincaré invariant.[17] This has the implication that there is one or more infinite-dimensional representation of the Lorentz group acting on Fock space.[nb 4] One way to guarantee the existence of such representations is the existence of a Lagrangian description (with modest requirements imposed, see the reference) of the system using the canonical formalism, from which a realization of the generators of the Lorentz group may be deduced.[18]

The transformations of field operators illustrate the complementary role played by the finite-dimensional representations of the Lorentz group and the infinite-dimensional unitary representations of the Poincare group, witnessing the deep unity between mathematics and physics.[19] For illustration, consider the definition an Template:Mvar-component field operator:[20] A relativistic field operator is a set of Template:Mvar operator valued functions on spacetime which transforms under proper Poincaré transformations Template:Math according to[21][22]

Here Template:Math is the unitary operator representing Template:Math on the Hilbert space on which Template:Math is defined and Template:Mvar is an Template:Mvar-dimensional representation of the Lorentz group. The transformation rule is the second Wightman axiom of quantum field theory.

By considerations of differential constraints that the field operator must be subjected to in order to describe a single particle with definite mass Template:Mvar and spin Template:Mvar (or helicity), it is deduced that[23][nb 5] Template:NumBlk where Template:Math are interpreted as creation and annihilation operators respectively. The creation operator Template:Math transforms according to[23][24]

and similarly for the annihilation operator. The point to be made is that the field operator transforms according to a finite-dimensional non-unitary representation of the Lorentz group, while the creation operator transforms under the infinite-dimensional unitary representation of the Poincare group characterized by the mass and spin Template:Math of the particle. The connection between the two are the wave functions, also called coefficient functions

that carry both the indices Template:Math operated on by Lorentz transformations and the indices Template:Math operated on by Poincaré transformations. This may be called the Lorentz–Poincaré connection.[25] To exhibit the connection, subject both sides of equation Template:EquationNote to a Lorentz transformation resulting in for e.g. Template:Mvar,

where Template:Mvar is the non-unitary Lorentz group representative of Template:Math and Template:Math is a unitary representative of the so-called Wigner rotation Template:Mvar associated to Template:Math and Template:Math that derives from the representation of the Poincaré group, and Template:Mvar is the spin of the particle.

All of the above formulas, including the definition of the field operator in terms of creation and annihilation operators, as well as the differential equations satisfied by the field operator for a particle with specified mass, spin and the Template:Math representation under which it is supposed to transform,[nb 6] and also that of the wave function, can be derived from group theoretical considerations alone once the frameworks of quantum mechanics and special relativity is given.[nb 7]

Speculative theories

In theories in which spacetime can have more than Template:Math dimensions, the generalized Lorentz groups Template:Math of the appropriate dimension take the place of Template:Math.[nb 8]

The requirement of Lorentz invariance takes on perhaps its most dramatic effect in string theory. Classical relativistic strings can be handled in the Lagrangian framework by using the Nambu–Goto action.[26] This results in a relativistically invariant theory in any spacetime dimension.[27] But as it turns out, the theory of open and closed bosonic strings (the simplest string theory) is impossible to quantize in such a way that the Lorentz group is represented on the space of states (a Hilbert space) unless the dimension of spacetime is 26.[28] The corresponding result for superstring theory is again deduced demanding Lorentz invariance, but now with supersymmetry. In these theories the Poincaré algebra is replaced by a supersymmetry algebra which is a [[graded Lie algebra|Template:Math-graded Lie algebra]] extending the Poincaré algebra. The structure of such an algebra is to a large degree fixed by the demands of Lorentz invariance. In particular, the fermionic operators (grade Template:Math) belong to a Template:Math or Template:Math representation space of the (ordinary) Lorentz Lie algebra.[29] The only possible dimension of spacetime in such theories is 10.[30]

Finite-dimensional representations

Representation theory of groups in general, and Lie groups in particular, is a very rich subject. The Lorentz group has some properties that makes it "agreeable" and others that make it "not very agreeable" within the context of representation theory; the group is simple and thus semisimple, but is not connected, and none of its components are simply connected. Furthermore, the Lorentz group is not compact.[31]

For finite-dimensional representations, the presence of semisimplicity means that the Lorentz group can be dealt with the same way as other semisimple groups using a well-developed theory. In addition, all representations are built from the irreducible ones, since the Lie algebra possesses the complete reducibility property.[nb 9][32] But, the non-compactness of the Lorentz group, in combination with lack of simple connectedness, cannot be dealt with in all the aspects as in the simple framework that applies to simply connected, compact groups. Non-compactness implies, for a connected simple Lie group, that no nontrivial finite-dimensional unitary representations exist.[33] Lack of simple connectedness gives rise to spin representations of the group.[34] The non-connectedness means that, for representations of the full Lorentz group, time reversal and reversal of spatial orientation have to be dealt with separately.[35][36]

History

The development of the finite-dimensional representation theory of the Lorentz group mostly follows that of representation theory in general. Lie theory originated with Sophus Lie in 1873.[37][38] By 1888 the classification of simple Lie algebras was essentially completed by Wilhelm Killing.[39][40] In 1913 the theorem of highest weight for representations of simple Lie algebras, the path that will be followed here, was completed by Élie Cartan.[41][42] Richard Brauer was during the period of 1935–38 largely responsible for the development of the Weyl-Brauer matrices describing how spin representations of the Lorentz Lie algebra can be embedded in Clifford algebras.[43][44] The Lorentz group has also historically received special attention in representation theory, see History of infinite-dimensional unitary representations below, due to its exceptional importance in physics. Mathematicians Hermann Weyl[41][45][37][46][47] and Harish-Chandra[48][49] and physicists Eugene Wigner[50][51] and Valentine Bargmann[52][53][54] made substantial contributions both to general representation theory and in particular to the Lorentz group.[55] Physicist Paul Dirac was perhaps the first to manifestly knit everything together in a practical application of major lasting importance with the Dirac equation in 1928.[56][57][nb 10]

The Lie algebra

This section addresses the irreducible complex linear representations of the complexification of the Lie algebra of the Lorentz group. A convenient basis for is given by the three generators Template:Math of rotations and the three generators Template:Math of boosts. They are explicitly given in conventions and Lie algebra bases.

The Lie algebra is complexified, and the basis is changed to the components of its two ideals[58]

The components of Template:Math and Template:Math separately satisfy the commutation relations of the Lie algebra and, moreover, they commute with each other,[59]

where Template:Math are indices which each take values Template:Math, and Template:Math is the three-dimensional Levi-Civita symbol. Let and denote the complex linear span of Template:Math and Template:Math respectively.

One has the isomorphisms[60][nb 11] Template:NumBlk where is the complexification of

The utility of these isomorphisms comes from the fact that all irreducible representations of , and hence all irreducible complex linear representations of are known. The irreducible complex linear representation of is isomorphic to one of the highest weight representations. These are explicitly given in complex linear representations of

The unitarian trick

The Lie algebra is the Lie algebra of It contains the compact subgroup Template:Math with Lie algebra The latter is a compact real form of Thus from the first statement of the unitarian trick, representations of Template:Math are in one-to-one correspondence with holomorphic representations of

By compactness, the Peter–Weyl theorem applies to Template:Math,[61] and hence orthonormality of irreducible characters may be appealed to. The irreducible unitary representations of Template:Math are precisely the tensor products of irreducible unitary representations of Template:Math.[62]

By appeal to simple connectedness, the second statement of the unitarian trick is applied. The objects in the following list are in one-to-one correspondence:

- Holomorphic representations of

- Smooth representations of Template:Math

- Real linear representations of

- Complex linear representations of

Tensor products of representations appear at the Lie algebra level as either of[nb 12] Template:NumBlk where Template:Math is the identity operator. Here, the latter interpretation, which follows from Template:EquationNote, is intended. The highest weight representations of are indexed by Template:Mvar for Template:Math. (The highest weights are actually Template:Math, but the notation here is adapted to that of ) The tensor products of two such complex linear factors then form the irreducible complex linear representations of

Finally, the -linear representations of the real forms of the far left, , and the far right, [nb 13] in Template:EquationNote are obtained from the -linear representations of characterized in the previous paragraph.

The (μ, ν)-representations of sl(2, C)

The complex linear representations of the complexification of obtained via isomorphisms in Template:EquationNote, stand in one-to-one correspondence with the real linear representations of [63] The set of all real linear irreducible representations of are thus indexed by a pair Template:Math. The complex linear ones, corresponding precisely to the complexification of the real linear representations, are of the form Template:Math, while the conjugate linear ones are the Template:Math.[63] All others are real linear only. The linearity properties follow from the canonical injection, the far right in Template:EquationNote, of into its complexification. Representations on the form Template:Math or Template:Math are given by real matrices (the latter are not irreducible). Explicitly, the real linear Template:Math-representations of are where are the complex linear irreducible representations of and their complex conjugate representations. (The labeling is usually in the mathematics literature Template:Math, but half-integers are chosen here to conform with the labeling for the Lie algebra.) Here the tensor product is interpreted in the former sense of Template:EquationNote. These representations are concretely realized below.

The (m, n)-representations of so(3; 1)

Via the displayed isomorphisms in Template:EquationNote and knowledge of the complex linear irreducible representations of upon solving for Template:Math and Template:Math, all irreducible representations of and, by restriction, those of are obtained. The representations of obtained this way are real linear (and not complex or conjugate linear) because the algebra is not closed upon conjugation, but they are still irreducible.[60] Since is semisimple,[60] all its representations can be built up as direct sums of the irreducible ones.

Thus the finite dimensional irreducible representations of the Lorentz algebra are classified by an ordered pair of half-integers Template:Math and Template:Math, conventionally written as one of where Template:Mvar is a finite-dimensional vector space. These are, up to a similarity transformation, uniquely given by[nb 14] Template:NumBlk where Template:Math is the Template:Mvar-dimensional unit matrix and are the Template:Math-dimensional irreducible representations of also termed spin matrices or angular momentum matrices. These are explicitly given as[64] where Template:Math denotes the Kronecker delta. In components, with Template:Math, Template:Math, the representations are given by[65]

Common representations

| Template:Math | Template:Math | Template:Math | Template:Math | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template:Math | Scalar (1) | Left-handed Weyl spinor (2) |

Self-dual 2-form (3) |

(4) |

| Template:Math | Right-handed Weyl spinor (2) |

4-vector (4) | (6) | (8) |

| Template:Math | Anti-self-dual 2-form (3) |

(6) | Traceless symmetric tensor (9) |

(12) |

| Template:Math | (4) | (8) | (12) | (16) |

- The Template:Math representation is the one-dimensional trivial representation and is carried by relativistic scalar field theories.

- Fermionic supersymmetry generators transform under one of the Template:Math or Template:Math representations (Weyl spinors).[29]

- The four-momentum of a particle (either massless or massive) transforms under the Template:Math representation, a four-vector.

- A physical example of a (1,1) traceless symmetric tensor field is the traceless[nb 15] part of the energy–momentum tensor Template:Mvar.[66][nb 16]

Off-diagonal direct sums

Since for any irreducible representation for which Template:Math it is essential to operate over the field of complex numbers, the direct sum of representations Template:Math and Template:Math have particular relevance to physics, since it permits to use linear operators over real numbers.

- Template:Math is the bispinor representation. See also Dirac spinor and Weyl spinors and bispinors below.

- Template:Math is the Rarita–Schwinger field representation.

- Template:Math would be the symmetry of the hypothesized gravitino.[nb 17] It can be obtained from the Template:Math representation.

- Template:Math is the representation of a parity-invariant 2-form field (a.k.a. curvature form). The electromagnetic field tensor transforms under this representation.

The group

The approach in this section is based on theorems that, in turn, are based on the fundamental Lie correspondence.[67] The Lie correspondence is in essence a dictionary between connected Lie groups and Lie algebras.[68] The link between them is the exponential mapping from the Lie algebra to the Lie group, denoted

If for some vector space Template:Mvar is a representation, a representation Template:Math of the connected component of Template:Mvar is defined by Template:NumBlk

This definition applies whether the resulting representation is projective or not.

Surjectiveness of exponential map for SO(3, 1)

From a practical point of view, it is important whether the first formula in Template:EquationNote can be used for all elements of the group. It holds for all , however, in the general case, e.g. for , not all Template:Math are in the image of Template:Math.

But is surjective. One way to show this is to make use of the isomorphism the latter being the Möbius group. It is a quotient of (see the linked article). The quotient map is denoted with The map is onto.[69] Apply Template:EquationNote with Template:Mvar being the differential of Template:Mvar at the identity. Then

Since the left hand side is surjective (both Template:Math and Template:Mvar are), the right hand side is surjective and hence is surjective.[70] Finally, recycle the argument once more, but now with the known isomorphism between Template:Math and to find that Template:Math is onto for the connected component of the Lorentz group.

Fundamental group

The Lorentz group is doubly connected, i. e. Template:Math is a group with two equivalence classes of loops as its elements. Template:Math proof

Projective representations

Since Template:Math has two elements, some representations of the Lie algebra will yield projective representations.[71][nb 18] Once it is known whether a representation is projective, formula Template:EquationNote applies to all group elements and all representations, including the projective ones — with the understanding that the representative of a group element will depend on which element in the Lie algebra (the Template:Mvar in Template:EquationNote) is used to represent the group element in the standard representation.

For the Lorentz group, the Template:Math-representation is projective when Template:Math is a half-integer. See Template:Section link.

For a projective representation Template:Math of Template:Math, it holds that[72] Template:NumBlk since any loop in Template:Math traversed twice, due to the double connectedness, is contractible to a point, so that its homotopy class is that of a constant map. It follows that Template:Math is a double-valued function. It is not possible to consistently choose a sign to obtain a continuous representation of all of Template:Math, but this is possible locally around any point.[33]

The covering group SL(2, C)

Consider as a real Lie algebra with basis

where the sigmas are the Pauli matrices. From the relations Template:NumBlk is obtained Template:NumBlk which are exactly on the form of the Template:Math-dimensional version of the commutation relations for (see conventions and Lie algebra bases below). Thus, the map Template:Math, Template:Math, extended by linearity is an isomorphism. Since is simply connected, it is the universal covering group of Template:Math.

A geometric view

Let Template:Math be a path from Template:Math to Template:Math, denote its homotopy class by Template:Math and let Template:Mvar be the set of all such homotopy classes. Define the set Template:NumBlk and endow it with the multiplication operation Template:NumBlk where is the path multiplication of and :

With this multiplication, Template:Mvar becomes a group isomorphic to [73] the universal covering group of Template:Math. Since each Template:Mvar has two elements, by the above construction, there is a 2:1 covering map Template:Math. According to covering group theory, the Lie algebras and of Template:Mvar are all isomorphic. The covering map Template:Math is simply given by Template:Math.

An algebraic view

For an algebraic view of the universal covering group, let act on the set of all Hermitian Template:Gaps matrices by the operation[72] Template:NumBlk

The action on is linear. An element of may be written in the form Template:NumBlk

The map Template:Math is a group homomorphism into Thus is a 4-dimensional representation of . Its kernel must in particular take the identity matrix to itself, Template:Math and therefore Template:Math. Thus Template:Math for Template:Mvar in the kernel so, by Schur's lemma,[nb 19] Template:Mvar is a multiple of the identity, which must be Template:Math since Template:Math.[74] The space is mapped to Minkowski space Template:Math, via Template:NumBlk

The action of Template:Math on preserves determinants. The induced representation Template:Math of on via the above isomorphism, given by Template:NumBlk preserves the Lorentz inner product since

This means that Template:Math belongs to the full Lorentz group Template:Math. By the main theorem of connectedness, since is connected, its image under Template:Math in Template:Math is connected, and hence is contained in Template:Math.

It can be shown that the Lie map of is a Lie algebra isomorphism: [nb 20] The map Template:Math is also onto.[nb 21]

Thus , since it is simply connected, is the universal covering group of Template:Math, isomorphic to the group Template:Mvar of above. Template:Hidden end

Non-surjectiveness of exponential mapping for SL(2, C)

The exponential mapping is not onto.[75] The matrix Template:NumBlk is in but there is no such that Template:Math.[nb 22]

In general, if Template:Mvar is an element of a connected Lie group Template:Mvar with Lie algebra then, by Template:EquationNote, Template:NumBlk

The matrix Template:Mvar can be written Template:NumBlk

Realization of representations of Template:Math and Template:Math and their Lie algebras

The complex linear representations of and are more straightforward to obtain than the representations. They can be (and usually are) written down from scratch. The holomorphic group representations (meaning the corresponding Lie algebra representation is complex linear) are related to the complex linear Lie algebra representations by exponentiation. The real linear representations of are exactly the Template:Math-representations. They can be exponentiated too. The Template:Math-representations are complex linear and are (isomorphic to) the highest weight-representations. These are usually indexed with only one integer (but half-integers are used here).

The mathematics convention is used in this section for convenience. Lie algebra elements differ by a factor of Template:Math and there is no factor of Template:Math in the exponential mapping compared to the physics convention used elsewhere. Let the basis of be[76] Template:NumBlk

This choice of basis, and the notation, is standard in the mathematical literature.

Complex linear representations

The irreducible holomorphic Template:Math-dimensional representations can be realized on the space of homogeneous polynomial of degree Template:Math in 2 variables [77][78] the elements of which are

The action of is given by[79][80] Template:NumBlk

The associated -action is, using Template:EquationNote and the definition above, for the basis elements of [81] Template:NumBlk

With a choice of basis for , these representations become matrix Lie algebras.

Real linear representations

The Template:Math-representations are realized on a space of polynomials in homogeneous of degree Template:Mvar in and homogeneous of degree Template:Mvar in [78] The representations are given by[82] Template:NumBlk

By employing Template:EquationNote again it is found that Template:NumBlk

In particular for the basis elements, Template:NumBlk

Properties of the (m, n) representations

The Template:Math representations, defined above via Template:EquationNote (as restrictions to the real form ) of tensor products of irreducible complex linear representations Template:Math and Template:Math of are irreducible, and they are the only irreducible representations.[61]

- Irreducibility follows from the unitarian trick[83] and that a representation Template:Math of Template:Math is irreducible if and only if Template:Math,[nb 23] where Template:Math are irreducible representations of Template:Math.

- Uniqueness follows from that the Template:Math are the only irreducible representations of Template:Math, which is one of the conclusions of the theorem of the highest weight.[84]

Dimension

The Template:Math representations are Template:Math-dimensional.[85] This follows easiest from counting the dimensions in any concrete realization, such as the one given in representations of and . For a Lie general algebra the Weyl dimension formula,[86] applies, where Template:Math is the set of positive roots, Template:Math is the highest weight, and Template:Math is half the sum of the positive roots. The inner product is that of the Lie algebra invariant under the action of the Weyl group on the Cartan subalgebra. The roots (really elements of ) are via this inner product identified with elements of For the formula reduces to Template:Math, where the present notation must be taken into account. The highest weight is Template:Math.[87] By taking tensor products, the result follows.

Faithfulness

If a representation Template:Math of a Lie group Template:Math is not faithful, then Template:Math is a nontrivial normal subgroup.[88] There are three relevant cases.

- Template:Math is non-discrete and abelian.

- Template:Math is non-discrete and non-abelian.

- Template:Math is discrete. In this case Template:Math, where Template:Math is the center of Template:Math.[nb 24]

In the case of Template:Math, the first case is excluded since Template:Math is semi-simple.[nb 25] The second case (and the first case) is excluded because Template:Math is simple.[nb 26] For the third case, Template:Math is isomorphic to the quotient But is the center of It follows that the center of Template:Math is trivial, and this excludes the third case. The conclusion is that every representation Template:Math and every projective representation Template:Math for Template:Math finite-dimensional vector spaces are faithful.

By using the fundamental Lie correspondence, the statements and the reasoning above translate directly to Lie algebras with (abelian) nontrivial non-discrete normal subgroups replaced by (one-dimensional) nontrivial ideals in the Lie algebra,[89] and the center of Template:Math replaced by the center of The center of any semisimple Lie algebra is trivial[90] and is semi-simple and simple, and hence has no non-trivial ideals.

A related fact is that if the corresponding representation of is faithful, then the representation is projective. Conversely, if the representation is non-projective, then the corresponding representation is not faithful, but is Template:Math.

Non-unitarity

The Template:Math Lie algebra representation is not Hermitian. Accordingly, the corresponding (projective) representation of the group is never unitary.[nb 27] This is due to the non-compactness of the Lorentz group. In fact, a connected simple non-compact Lie group cannot have any nontrivial unitary finite-dimensional representations.[33] There is a topological proof of this.[91] Let Template:Math, where Template:Math is finite-dimensional, be a continuous unitary representation of the non-compact connected simple Lie group Template:Mvar. Then Template:Math where Template:Math is the compact subgroup of Template:Math consisting of unitary transformations of Template:Mvar. The kernel of Template:Math is a normal subgroup of Template:Mvar. Since Template:Mvar is simple, Template:Math is either all of Template:Mvar, in which case Template:Math is trivial, or Template:Math is trivial, in which case Template:Math is faithful. In the latter case Template:Math is a diffeomorphism onto its image,[92] Template:Math and Template:Math is a Lie group. This would mean that Template:Math is an embedded non-compact Lie subgroup of the compact group Template:Math. This is impossible with the subspace topology on Template:Math since all embedded Lie subgroups of a Lie group are closed[93] If Template:Math were closed, it would be compact,[nb 28] and then Template:Mvar would be compact,[nb 29] contrary to assumption.[nb 30]

In the case of the Lorentz group, this can also be seen directly from the definitions. The representations of Template:Math and Template:Math used in the construction are Hermitian. This means that Template:Math is Hermitian, but Template:Math is anti-Hermitian.[94] The non-unitarity is not a problem in quantum field theory, since the objects of concern are not required to have a Lorentz-invariant positive definite norm.[95]

Restriction to SO(3)

The Template:Math representation is, however, unitary when restricted to the rotation subgroup Template:Math, but these representations are not irreducible as representations of SO(3). A Clebsch–Gordan decomposition can be applied showing that an Template:Math representation have Template:Math-invariant subspaces of highest weight (spin) Template:Math,[96] where each possible highest weight (spin) occurs exactly once. A weight subspace of highest weight (spin) Template:Math is Template:Math-dimensional. So for example, the (Template:Sfrac, Template:Sfrac) representation has spin 1 and spin 0 subspaces of dimension 3 and 1 respectively.

Since the angular momentum operator is given by Template:Math, the highest spin in quantum mechanics of the rotation sub-representation will be Template:Math and the "usual" rules of addition of angular momenta and the formalism of 3-j symbols, 6-j symbols, etc. applies.[97]

Spinors

It is the Template:Math-invariant subspaces of the irreducible representations that determine whether a representation has spin. From the above paragraph, it is seen that the Template:Math representation has spin if Template:Math is half-integer. The simplest are Template:Math and Template:Math, the Weyl-spinors of dimension Template:Math. Then, for example, Template:Math and Template:Math are a spin representations of dimensions Template:Math and Template:Math respectively. According to the above paragraph, there are subspaces with spin both Template:Math and Template:Math in the last two cases, so these representations cannot likely represent a single physical particle which must be well-behaved under Template:Math. It cannot be ruled out in general, however, that representations with multiple Template:Math subrepresentations with different spin can represent physical particles with well-defined spin. It may be that there is a suitable relativistic wave equation that projects out unphysical components, leaving only a single spin.[98]

Construction of pure spin Template:Math representations for any Template:Math (under Template:Math) from the irreducible representations involves taking tensor products of the Dirac-representation with a non-spin representation, extraction of a suitable subspace, and finally imposing differential constraints.[99]

Dual representations

The following theorems are applied to examine whether the dual representation of an irreducible representation is isomorphic to the original representation:

- The set of weights of the dual representation of an irreducible representation of a semisimple Lie algebra is, including multiplicities, the negative of the set of weights for the original representation.[100]

- Two irreducible representations are isomorphic if and only if they have the same highest weight.[nb 31]

- For each semisimple Lie algebra there exists a unique element Template:Math of the Weyl group such that if Template:Math is a dominant integral weight, then Template:Math is again a dominant integral weight.[101]

- If is an irreducible representation with highest weight Template:Math, then has highest weight Template:Math.[101]

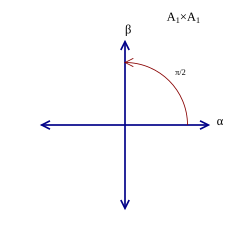

Here, the elements of the Weyl group are considered as orthogonal transformations, acting by matrix multiplication, on the real vector space of roots. If Template:Math is an element of the Weyl group of a semisimple Lie algebra, then Template:Math. In the case of the Weyl group is Template:Math.[102] It follows that each Template:Math is isomorphic to its dual The root system of is shown in the figure to the right.[nb 32] The Weyl group is generated by where is reflection in the plane orthogonal to Template:Math as Template:Math ranges over all roots.[nb 33] Inspection shows that Template:Math so Template:Math. Using the fact that if Template:Math are Lie algebra representations and Template:Math, then Template:Math,[103] the conclusion for Template:Math is

Complex conjugate representations

If Template:Math is a representation of a Lie algebra, then is a representation, where the bar denotes entry-wise complex conjugation in the representative matrices. This follows from that complex conjugation commutes with addition and multiplication.[104] In general, every irreducible representation Template:Math of can be written uniquely as Template:Math, where[105] with holomorphic (complex linear) and anti-holomorphic (conjugate linear). For since is holomorphic, is anti-holomorphic. Direct examination of the explicit expressions for and in equation Template:EquationNote below shows that they are holomorphic and anti-holomorphic respectively. Closer examination of the expression Template:EquationNote also allows for identification of and for as

Using the above identities (interpreted as pointwise addition of functions), for Template:Math yields where the statement for the group representations follow from Template:Math. It follows that the irreducible representations Template:Math have real matrix representatives if and only if Template:Math. Reducible representations on the form Template:Math have real matrices too.

The adjoint representation, the Clifford algebra, and the Dirac spinor representation

In general representation theory, if Template:Math is a representation of a Lie algebra then there is an associated representation of on Template:Math, also denoted Template:Mvar, given by Template:NumBlk

Likewise, a representation Template:Math of a group Template:Mvar yields a representation Template:Math on Template:Math of Template:Mvar, still denoted Template:Math, given by[106] Template:NumBlk

If Template:Mvar and Template:Math are the standard representations on and if the action is restricted to then the two above representations are the adjoint representation of the Lie algebra and the adjoint representation of the group respectively. The corresponding representations (some or ) always exist for any matrix Lie group, and are paramount for investigation of the representation theory in general, and for any given Lie group in particular.

Applying this to the Lorentz group, if Template:Math is a projective representation, then direct calculation using Template:EquationNote shows that the induced representation on Template:Math is a proper representation, i.e. a representation without phase factors.

In quantum mechanics this means that if Template:Math or Template:Math is a representation acting on some Hilbert space Template:Mvar, then the corresponding induced representation acts on the set of linear operators on Template:Mvar. As an example, the induced representation of the projective spin Template:Math representation on Template:Math is the non-projective 4-vector (Template:Sfrac, Template:Sfrac) representation.[107]

For simplicity, consider only the "discrete part" of Template:Math, that is, given a basis for Template:Mvar, the set of constant matrices of various dimension, including possibly infinite dimensions. The induced 4-vector representation of above on this simplified Template:Math has an invariant 4-dimensional subspace that is spanned by the four gamma matrices.[108] (The metric convention is different in the linked article.) In a corresponding way, the complete Clifford algebra of spacetime, whose complexification is generated by the gamma matrices decomposes as a direct sum of representation spaces of a scalar irreducible representation (irrep), the Template:Math, a pseudoscalar irrep, also the Template:Math, but with parity inversion eigenvalue Template:Math, see the next section below, the already mentioned vector irrep, Template:Math, a pseudovector irrep, Template:Math with parity inversion eigenvalue +1 (not −1), and a tensor irrep, Template:Math.[109] The dimensions add up to Template:Math. In other words, Template:NumBlk where, as is customary, a representation is confused with its representation space.

The Template:Math spin representation

The six-dimensional representation space of the tensor Template:Math-representation inside has two roles. The[110] Template:NumBlk where are the gamma matrices, the sigmas, only Template:Math of which are non-zero due to antisymmetry of the bracket, span the tensor representation space. Moreover, they have the commutation relations of the Lorentz Lie algebra,[111] Template:NumBlk and hence constitute a representation (in addition to spanning a representation space) sitting inside the Template:Math spin representation. For details, see bispinor and Dirac algebra.

The conclusion is that every element of the complexified in Template:Math (i.e. every complex Template:Gaps matrix) has well defined Lorentz transformation properties. In addition, it has a spin-representation of the Lorentz Lie algebra, which upon exponentiation becomes a spin representation of the group, acting on making it a space of bispinors.

Reducible representations

There is a multitude of other representations that can be deduced from the irreducible ones, such as those obtained by taking direct sums, tensor products, and quotients of the irreducible representations. Other methods of obtaining representations include the restriction of a representation of a larger group containing the Lorentz group, e.g. and the Poincaré group. These representations are in general not irreducible.

The Lorentz group and its Lie algebra have the complete reducibility property. This means that every representation reduces to a direct sum of irreducible representations. The reducible representations will therefore not be discussed.

Space inversion and time reversal

The (possibly projective) Template:Math representation is irreducible as a representation Template:Math, the identity component of the Lorentz group, in physics terminology the proper orthochronous Lorentz group. If Template:Math it can be extended to a representation of all of Template:Math, the full Lorentz group, including space parity inversion and time reversal. The representations Template:Math can be extended likewise.[112]

Space parity inversion

For space parity inversion, the adjoint action Template:Math of Template:Math on is considered, where Template:Math is the standard representative of space parity inversion, Template:Math, given by Template:NumBlk

It is these properties of Template:Math and Template:Math under Template:Mvar that motivate the terms vector for Template:Math and pseudovector or axial vector for Template:Math. In a similar way, if Template:Math is any representation of and Template:Math is its associated group representation, then Template:Math acts on the representation of Template:Math by the adjoint action, Template:Math for Template:Math. If Template:Math is to be included in Template:Math, then consistency with Template:EquationNote requires that

holds, where Template:Math and Template:Math are defined as in the first section. This can hold only if Template:Math and Template:Math have the same dimensions, i.e. only if Template:Math. When Template:Math then Template:Math can be extended to an irreducible representation of Template:Math, the orthochronous Lorentz group. The parity reversal representative Template:Math does not come automatically with the general construction of the Template:Math representations. It must be specified separately. The matrix Template:Math (or a multiple of modulus −1 times it) may be used in the Template:Math[113] representation.

If parity is included with a minus sign (the Template:Math matrix Template:Math) in the Template:Math representation, it is called a pseudoscalar representation.

Time reversal

Time reversal Template:Math, acts similarly on by[114] Template:NumBlk

By explicitly including a representative for Template:Math, as well as one for Template:Math, a representation of the full Lorentz group Template:Math is obtained. A subtle problem appears however in application to physics, in particular quantum mechanics. When considering the full Poincaré group, four more generators, the Template:Mvar, in addition to the Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar generate the group. These are interpreted as generators of translations. The time-component Template:Math is the Hamiltonian Template:Math. The operator Template:Math satisfies the relation[115] Template:NumBlk in analogy to the relations above with replaced by the full Poincaré algebra. By just cancelling the Template:Mvar's, the result Template:Math would imply that for every state Template:Math with positive energy Template:Mvar in a Hilbert space of quantum states with time-reversal invariance, there would be a state Template:Math with negative energy Template:Math. Such states do not exist. The operator Template:Math is therefore chosen antilinear and antiunitary, so that it anticommutes with Template:Mvar, resulting in Template:Math, and its action on Hilbert space likewise becomes antilinear and antiunitary.[116] It may be expressed as the composition of complex conjugation with multiplication by a unitary matrix.[117] This is mathematically sound, see Wigner's theorem, but with very strict requirements on terminology, Template:Math is not a representation.

When constructing theories such as QED which is invariant under space parity and time reversal, Dirac spinors may be used, while theories that do not, such as the electroweak force, must be formulated in terms of Weyl spinors. The Dirac representation, Template:Nowrap, is usually taken to include both space parity and time inversions. Without space parity inversion, it is not an irreducible representation.

The third discrete symmetry entering in the CPT theorem along with Template:Math and Template:Math, charge conjugation symmetry Template:Math, has nothing directly to do with Lorentz invariance.[118]

Action on function spaces

If Template:Mvar is a vector space of functions of a finite number of variables Template:Mvar, then the action on a scalar function given by Template:NumBlk produces another function Template:Math. Here Template:Math is an Template:Mvar-dimensional representation, and Template:Math is a possibly infinite-dimensional representation. A special case of this construction is when Template:Mvar is a space of functions defined on the a linear group Template:Mvar itself, viewed as a Template:Mvar-dimensional manifold embedded in (with Template:Mvar the dimension of the matrices).[119] This is the setting in which the Peter–Weyl theorem and the Borel–Weil theorem are formulated. The former demonstrates the existence of a Fourier decomposition of functions on a compact group into characters of finite-dimensional representations.[61] The latter theorem, providing more explicit representations, makes use of the unitarian trick to yield representations of complex non-compact groups, e.g.

The following exemplifies action of the Lorentz group and the rotation subgroup on some function spaces.

Euclidean rotations

The subgroup Template:Math of three-dimensional Euclidean rotations has an infinite-dimensional representation on the Hilbert space

where are the spherical harmonics. An arbitrary square integrable function Template:Mvar on the unit sphere can be expressed as[120] Template:NumBlk where the Template:Math are generalized Fourier coefficients.

The Lorentz group action restricts to that of Template:Math and is expressed as Template:NumBlk where the Template:Math are obtained from the representatives of odd dimension of the generators of rotation.

The Möbius group

Template:Main The identity component of the Lorentz group is isomorphic to the Möbius group Template:Math. This group can be thought of as conformal mappings of either the complex plane or, via stereographic projection, the Riemann sphere. In this way, the Lorentz group itself can be thought of as acting conformally on the complex plane or on the Riemann sphere.

In the plane, a Möbius transformation characterized by the complex numbers Template:Math acts on the plane according to[121] Template:NumBlk and can be represented by complex matrices Template:NumBlk since multiplication by a nonzero complex scalar does not change Template:Mvar. These are elements of and are unique up to a sign (since Template:Math give the same Template:Mvar), hence

The Riemann P-functions

Template:Main The Riemann P-functions, solutions of Riemann's differential equation, are an example of a set of functions that transform among themselves under the action of the Lorentz group. The Riemann P-functions are expressed as[122] Template:NumBlk where the Template:Math are complex constants. The P-function on the right hand side can be expressed using standard hypergeometric functions. The connection is[123] Template:NumBlk

The set of constants Template:Math in the upper row on the left hand side are the regular singular points of the Gauss' hypergeometric equation.[124] Its exponents, i. e. solutions of the indicial equation, for expansion around the singular point Template:Math are Template:Math and Template:Math ,corresponding to the two linearly independent solutions,[nb 34] and for expansion around the singular point Template:Math they are Template:Math and Template:Math.[125] Similarly, the exponents for Template:Math are Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar for the two solutions.[126]

One has thus Template:NumBlk where the condition (sometimes called Riemann's identity)[127] on the exponents of the solutions of Riemann's differential equation has been used to define Template:Math.

The first set of constants on the left hand side in Template:EquationNote, Template:Math denotes the regular singular points of Riemann's differential equation. The second set, Template:Math, are the corresponding exponents at Template:Math for one of the two linearly independent solutions, and, accordingly, Template:Math are exponents at Template:Math for the second solution.

Define an action of the Lorentz group on the set of all Riemann P-functions by first setting Template:NumBlk where Template:Math are the entries in Template:NumBlk for Template:Math a Lorentz transformation.

Define Template:NumBlk where Template:Mvar is a Riemann P-function. The resulting function is again a Riemann P-function. The effect of the Möbius transformation of the argument is that of shifting the poles to new locations, hence changing the critical points, but there is no change in the exponents of the differential equation the new function satisfies. The new function is expressed as Template:NumBlk where Template:NumBlk

Infinite-dimensional unitary representations

History

The Lorentz group Template:Math and its double cover also have infinite dimensional unitary representations, studied independently by Template:Harvtxt, Template:Harvtxt and Template:Harvtxt at the instigation of Paul Dirac.[128][129] This trail of development begun with Template:Harvtxt where he devised matrices Template:Math and Template:Math necessary for description of higher spin (compare Dirac matrices), elaborated upon by Template:Harvtxt, see also Template:Harvtxt, and proposed precursors of the Bargmann-Wigner equations.[130] In Template:Harvtxt he proposed a concrete infinite-dimensional representation space whose elements were called expansors as a generalization of tensors.[nb 35] These ideas were incorporated by Harish–Chandra and expanded with expinors as an infinite-dimensional generalization of spinors in his 1947 paper.

The Plancherel formula for these groups was first obtained by Gelfand and Naimark through involved calculations. The treatment was subsequently considerably simplified by Template:Harvtxt and Template:Harvtxt, based on an analogue for of the integration formula of Hermann Weyl for compact Lie groups.[131] Elementary accounts of this approach can be found in Template:Harvtxt and Template:Harvtxt.

The theory of spherical functions for the Lorentz group, required for harmonic analysis on the hyperboloid model of 3-dimensional hyperbolic space sitting in Minkowski space is considerably easier than the general theory. It only involves representations from the spherical principal series and can be treated directly, because in radial coordinates the Laplacian on the hyperboloid is equivalent to the Laplacian on This theory is discussed in Template:Harvtxt, Template:Harvtxt, Template:Harvtxt and the posthumous text of Template:Harvtxt.

Principal series for SL(2, C)

The principal series, or unitary principal series, are the unitary representations induced from the one-dimensional representations of the lower triangular subgroup Template:Mvar of Since the one-dimensional representations of Template:Mvar correspond to the representations of the diagonal matrices, with non-zero complex entries Template:Mvar and Template:Math, they thus have the form for Template:Mvar an integer, Template:Mvar real and with Template:Mvar. The representations are irreducible; the only repetitions, i.e. isomorphisms of representations, occur when Template:Mvar is replaced by Template:Math. By definition the representations are realized on Template:Math sections of line bundles on which is isomorphic to the Riemann sphere. When Template:Math, these representations constitute the so-called spherical principal series.

The restriction of a principal series to the maximal compact subgroup Template:Math of Template:Mvar can also be realized as an induced representation of Template:Mvar using the identification Template:Math, where Template:Math is the maximal torus in Template:Mvar consisting of diagonal matrices with Template:Math. It is the representation induced from the 1-dimensional representation Template:Math, and is independent of Template:Mvar. By Frobenius reciprocity, on Template:Mvar they decompose as a direct sum of the irreducible representations of Template:Mvar with dimensions Template:Math with Template:Mvar a non-negative integer.

Using the identification between the Riemann sphere minus a point and the principal series can be defined directly on by the formula[132]

Irreducibility can be checked in a variety of ways:

- The representation is already irreducible on Template:Mvar. This can be seen directly, but is also a special case of general results on irreducibility of induced representations due to François Bruhat and George Mackey, relying on the Bruhat decomposition Template:Math where Template:Mvar is the Weyl group element[133] .

- The action of the Lie algebra of Template:Mvar can be computed on the algebraic direct sum of the irreducible subspaces of Template:Mvar can be computed explicitly and the it can be verified directly that the lowest-dimensional subspace generates this direct sum as a -module.[8][134]

Complementary series for Template:Math

The for Template:Math, the complementary series is defined on for the inner product[135] with the action given by[136][137]

The representations in the complementary series are irreducible and pairwise non-isomorphic. As a representation of Template:Mvar, each is isomorphic to the Hilbert space direct sum of all the odd dimensional irreducible representations of Template:Math. Irreducibility can be proved by analyzing the action of on the algebraic sum of these subspaces[8][134] or directly without using the Lie algebra.[138][139]

Plancherel theorem for SL(2, C)

The only irreducible unitary representations of are the principal series, the complementary series and the trivial representation. Since Template:Math acts as Template:Math on the principal series and trivially on the remainder, these will give all the irreducible unitary representations of the Lorentz group, provided Template:Mvar is taken to be even.

To decompose the left regular representation of Template:Mvar on only the principal series are required. This immediately yields the decomposition on the subrepresentations the left regular representation of the Lorentz group, and the regular representation on 3-dimensional hyperbolic space. (The former only involves principal series representations with k even and the latter only those with Template:Math.)

The left and right regular representation Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar are defined on by

Now if Template:Mvar is an element of Template:Math, the operator defined by is Hilbert–Schmidt. Define a Hilbert space Template:Mvar by where and denotes the Hilbert space of Hilbert–Schmidt operators on [nb 36] Then the map Template:Mvar defined on Template:Math by extends to a unitary of onto Template:Mvar.

The map Template:Mvar satisfies the intertwining property

If Template:Math are in Template:Math then by unitarity

Thus if denotes the convolution of and and then[140]

The last two displayed formulas are usually referred to as the Plancherel formula and the Fourier inversion formula respectively.

The Plancherel formula extends to all By a theorem of Jacques Dixmier and Paul Malliavin, every smooth compactly supported function on is a finite sum of convolutions of similar functions, the inversion formula holds for such Template:Mvar. It can be extended to much wider classes of functions satisfying mild differentiability conditions.[61]

Classification of representations of Template:Math

The strategy followed in the classification of the irreducible infinite-dimensional representations is, in analogy to the finite-dimensional case, to assume they exist, and to investigate their properties. Thus first assume that an irreducible strongly continuous infinite-dimensional representation Template:Math on a Hilbert space Template:Mvar of Template:Math is at hand.[141] Since Template:Math is a subgroup, Template:Math is a representation of it as well. Each irreducible subrepresentation of Template:Math is finite-dimensional, and the Template:Math representation is reducible into a direct sum of irreducible finite-dimensional unitary representations of Template:Math if Template:Math is unitary.[142]

The steps are the following:[143]

- Choose a suitable basis of common eigenvectors of Template:Math and Template:Math.

- Compute matrix elements of Template:Math and Template:Math.

- Enforce Lie algebra commutation relations.

- Require unitarity together with orthonormality of the basis.[nb 37]

Step 1

One suitable choice of basis and labeling is given by

If this were a finite-dimensional representation, then Template:Math would correspond the lowest occurring eigenvalue Template:Math of Template:Math in the representation, equal to Template:Math, and Template:Math would correspond to the highest occurring eigenvalue, equal to Template:Math. In the infinite-dimensional case, Template:Math retains this meaning, but Template:Math does not.[66] For simplicity, it is assumed that a given Template:Mvar occurs at most once in a given representation (this is the case for finite-dimensional representations), and it can be shown[144] that the assumption is possible to avoid (with a slightly more complicated calculation) with the same results.

Step 2

The next step is to compute the matrix elements of the operators Template:Math and Template:Math forming the basis of the Lie algebra of The matrix elements of and (the complexified Lie algebra is understood) are known from the representation theory of the rotation group, and are given by[145][146] where the labels Template:Math and Template:Math have been dropped since they are the same for all basis vectors in the representation.

Due to the commutation relations the triple Template:Math is a vector operator[147] and the Wigner–Eckart theorem[148] applies for computation of matrix elements between the states represented by the chosen basis.[149] The matrix elements of

where the superscript Template:Math signifies that the defined quantities are the components of a spherical tensor operator of rank Template:Math (which explains the factor Template:Math as well) and the subscripts Template:Math are referred to as Template:Mvar in formulas below, are given by[150]

Here the first factors on the right hand sides are Clebsch–Gordan coefficients for coupling Template:Math with Template:Mvar to get Template:Mvar. The second factors are the reduced matrix elements. They do not depend on Template:Math or Template:Mvar, but depend on Template:Math and, of course, Template:Math. For a complete list of non-vanishing equations, see Template:Harvtxt.

Step 3

The next step is to demand that the Lie algebra relations hold, i.e. that

This results in a set of equations[151] for which the solutions are[152] where

Step 4

The imposition of the requirement of unitarity of the corresponding representation of the group restricts the possible values for the arbitrary complex numbers Template:Math and Template:Math. Unitarity of the group representation translates to the requirement of the Lie algebra representatives being Hermitian, meaning

This translates to[153] leading to[154] where Template:Math is the angle of Template:Math on polar form. For Template:Math follows and is chosen by convention. There are two possible cases:

- In this case Template:Math, Template:Mvar real,[155] This is the principal series. Its elements are denoted

- It follows:[156] Since Template:Math, Template:Math is real and positive for Template:Math, leading to Template:Math. This is complementary series. Its elements are denoted Template:Math

This shows that the representations of above are all infinite-dimensional irreducible unitary representations.

Explicit formulas

Conventions and Lie algebra bases

The metric of choice is given by Template:Math, and the physics convention for Lie algebras and the exponential mapping is used. These choices are arbitrary, but once they are made, fixed. One possible choice of basis for the Lie algebra is, in the 4-vector representation, given by:

The commutation relations of the Lie algebra are:[157]

In three-dimensional notation, these are[158]

The choice of basis above satisfies the relations, but other choices are possible. The multiple use of the symbol Template:Mvar above and in the sequel should be observed.

For example, a typical boost and a typical rotation exponentiate as, symmetric and orthogonal, respectively.

Weyl spinors and bispinors

By taking, in turn, Template:Math and Template:Math and by setting in the general expression Template:EquationNote, and by using the trivial relations Template:Math and Template:Math, it follows

These are the left-handed and right-handed Weyl spinor representations. They act by matrix multiplication on 2-dimensional complex vector spaces (with a choice of basis) Template:Math and Template:Math, whose elements Template:Math and Template:Math are called left- and right-handed Weyl spinors respectively. Given their direct sum as representations is formed,[159]

This is, up to a similarity transformation, the Template:Math Dirac spinor representation of It acts on the 4-component elements Template:Math of Template:Math, called bispinors, by matrix multiplication. The representation may be obtained in a more general and basis independent way using Clifford algebras. These expressions for bispinors and Weyl spinors all extend by linearity of Lie algebras and representations to all of Expressions for the group representations are obtained by exponentiation.

Open problems

The classification and characterization of the representation theory of the Lorentz group was completed in 1947. But in association with the Bargmann–Wigner programme, there are yet unresolved purely mathematical problems, linked to the infinite-dimensional unitary representations.

The irreducible infinite-dimensional unitary representations may have indirect relevance to physical reality in speculative modern theories since the (generalized) Lorentz group appears as the little group of the Poincaré group of spacelike vectors in higher spacetime dimension. The corresponding infinite-dimensional unitary representations of the (generalized) Poincaré group are the so-called tachyonic representations. Tachyons appear in the spectrum of bosonic strings and are associated with instability of the vacuum.[160][161] Even though tachyons may not be realized in nature, these representations must be mathematically understood in order to understand string theory. This is so since tachyon states turn out to appear in superstring theories too in attempts to create realistic models.[162]

One open problem is the completion of the Bargmann–Wigner programme for the isometry group Template:Math of the de Sitter spacetime Template:Math. Ideally, the physical components of wave functions would be realized on the hyperboloid Template:Math of radius Template:Math embedded in and the corresponding Template:Math covariant wave equations of the infinite-dimensional unitary representation to be known.[161]

See also

- Bargmann–Wigner equations

- Dirac algebra

- Gamma matrices

- Lorentz group

- Möbius transformation

- Poincaré group

- Representation theory of the Poincaré group

- Symmetry in quantum mechanics

- Wigner's classification

Remarks

Notes

Freely available online references

- Template:Cite arXiv Expanded version of the lectures presented at the second Modave summer school in mathematical physics (Belgium, August 2006).

- Template:Citation Group elements of SU(2) are expressed in closed form as finite polynomials of the Lie algebra generators, for all definite spin representations of the rotation group.

References

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation (the representation theory of SO(2,1) and SL(2, R); the second part on SO(3; 1) and SL(2, C), described in the introduction, was never published).

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Citation (free access)

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation (a general introduction for physicists)

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation (elementary treatment for SL(2,C))

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation (a detailed account for physicists)

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation (James K. Whittemore Lectures in Mathematics given at Yale University, 1967)

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation, Chapter 9, SL(2, C) and more general Lorentz groups

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Cite book

Template:Relativity Template:Manifolds

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "nb", but no corresponding <references group="nb"/> tag was found

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvtxt

- ↑ Template:Harvtxt

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvtxt

- ↑ Template:Harvtxt

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ These facts can be found in most introductory mathematics and physics texts. See e.g. Template:Harvtxt, Template:Harvtxt and Template:Harvtxt.

- ↑ Template:Harvtxt

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb, 1890, 1893. Primary source.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Primary source.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Primary source.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Primary source.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Primary source.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Primary source.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Primary source.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Primary source.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Primary source.

- ↑ Bargmann was also a mathematician. He worked as Albert Einsteins assistant at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton (Template:Harvtxt).

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Primary source.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Primary source.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ This is an application of Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb The equations follow from equations 5.6.7–8 and 5.6.14–15.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWeinberg 2002 loc=Section 2.7 - ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb This construction of the covering group is treated in paragraph 4, section 1, chapter 1 in Part II.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Equation 2.1.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Equation 2.4.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ See any text on basic group theory.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Propositions 3 and 6 paragraph 2.5.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb See exercise 1, Chapter 6.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb p.4.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Proposition 1.20.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb This is outlined (very briefly) on page 232, hardly more than a footnote.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb See appendix D.3

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Section 5.4.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Equation 2.6.5.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Equation following 2.6.6.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ For a detailed discussion of the spin 0, Template:Sfrac and 1 cases, see Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb See section 6.1 for more examples, both finite-dimensional and infinite-dimensional.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 134.0 134.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Chapter 2. Equation 2.12.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 161.0 161.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb