Matrix (mathematics): Difference between revisions

imported>D.Lazard →Size: When matices do not represent linear maps, column vectors and row vectors are nonsensical tems |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 17:28, 3 February 2025

Template:Short description Template:Hatnote group Template:Good article

In mathematics, a matrix (Template:Plural form: matrices) is a rectangular array or table of numbers, symbols, or expressions, with elements or entries arranged in rows and columns, which is used to represent a mathematical object or property of such an object.

For example, is a matrix with two rows and three columns. This is often referred to as a "two-by-three matrix", a " matrix", or a matrix of dimension .

Matrices are commonly related to linear algebra. Notable exceptions include incidence matrices and adjacency matrices in graph theory.[1] This article focuses on matrices related to linear algebra, and, unless otherwise specified, all matrices represent linear maps or may be viewed as such.

Square matrices, matrices with the same number of rows and columns, play a major role in matrix theory. Square matrices of a given dimension form a noncommutative ring, which is one of the most common examples of a noncommutative ring. The determinant of a square matrix is a number associated with the matrix, which is fundamental for the study of a square matrix; for example, a square matrix is invertible if and only if it has a nonzero determinant and the eigenvalues of a square matrix are the roots of a polynomial determinant.

In geometry, matrices are widely used for specifying and representing geometric transformations (for example rotations) and coordinate changes. In numerical analysis, many computational problems are solved by reducing them to a matrix computation, and this often involves computing with matrices of huge dimensions. Matrices are used in most areas of mathematics and scientific fields, either directly, or through their use in geometry and numerical analysis.

Matrix theory is the branch of mathematics that focuses on the study of matrices. It was initially a sub-branch of linear algebra, but soon grew to include subjects related to graph theory, algebra, combinatorics and statistics.

Definition

A matrix is a rectangular array of numbers (or other mathematical objects), called the entries of the matrix. Matrices are subject to standard operations such as addition and multiplication.[2] Most commonly, a matrix over a field F is a rectangular array of elements of F.[3][4] A real matrix and a complex matrix are matrices whose entries are respectively real numbers or complex numbers. More general types of entries are discussed below. For instance, this is a real matrix:

The numbers, symbols, or expressions in the matrix are called its entries or its elements. The horizontal and vertical lines of entries in a matrix are called rows and columns, respectively.

Size

The size of a matrix is defined by the number of rows and columns it contains. There is no limit to the number of rows and columns, that a matrix (in the usual sense) can have as long as they are positive integers. A matrix with rows and columns is called an matrix, or -by- matrix, where and are called its dimensions. For example, the matrix above is a matrix.

Matrices with a single row are called row matrices, and those with a single column are called column matrices. When vectors are involved, the terms row vector and column vector are commonly used instead. A matrix with the same number of rows and columns is called a square matrix.[5] A matrix with an infinite number of rows or columns (or both) is called an infinite matrix. In some contexts, such as computer algebra programs, it is useful to consider a matrix with no rows or no columns, called an empty matrix.

| Name| | Size | Example | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Row matrix | 1Template:Nbsp×Template:Nbspn | A matrix with one row, sometimes used to represent a vector | |

| Column matrix | nTemplate:Nbsp×Template:Nbsp1 | A matrix with one column, sometimes used to represent a vector | |

| Square matrix | nTemplate:Nbsp×Template:Nbspn | A matrix with the same number of rows and columns, sometimes used to represent a linear transformation from a vector space to itself, such as reflection, rotation, or shearing. |

Notation

The specifics of symbolic matrix notation vary widely, with some prevailing trends. Matrices are commonly written in square brackets or parentheses, so that an matrix is represented as This may be abbreviated by writing only a single generic term, possibly along with indices, as in or in the case that .

Matrices are usually symbolized using upper-case letters (such as in the examples above), while the corresponding lower-case letters, with two subscript indices (e.g., , or ), represent the entries. In addition to using upper-case letters to symbolize matrices, many authors use a special typographical style, commonly boldface Roman (non-italic), to further distinguish matrices from other mathematical objects. An alternative notation involves the use of a double-underline with the variable name, with or without boldface style, as in .

The entry in the Template:Math-th row and Template:Math-th column of a matrix Template:Math is sometimes referred to as the or entry of the matrix, and commonly denoted by or . Alternative notations for that entry are and . For example, the entry of the following matrix is Template:Math (also denoted , , or ):

Sometimes, the entries of a matrix can be defined by a formula such as . For example, each of the entries of the following matrix is determined by the formula .

In this case, the matrix itself is sometimes defined by that formula, within square brackets or double parentheses. For example, the matrix above is defined as or . If matrix size is , the above-mentioned formula is valid for any and any . This can be specified separately or indicated using as a subscript. For instance, the matrix above is , and can be defined as or .

Some programming languages utilize doubly subscripted arrays (or arrays of arrays) to represent an Template:Math-by-Template:Math matrix. Some programming languages start the numbering of array indexes at zero, in which case the entries of an Template:Math-by-Template:Math matrix are indexed by and .[6] This article follows the more common convention in mathematical writing where enumeration starts from Template:Math.

The set of all Template:Math-by-Template:Math real matrices is often denoted or The set of all Template:Math-by-Template:Math matrices over another field, or over a ring Template:Math, is similarly denoted or If Template:Math, such as in the case of square matrices, one does not repeat the dimension: or Template:Nowrap Often, , or , is used in place of

Basic operations

Several basic operations can be applied to matrices. Some, such as transposition and submatrix do not depend on the nature of the entries. Others, such as matrix addition, scalar multiplication, matrix multiplication, and row operations involve operations on matrix entries and therefore require that matrix entries are numbers or belong to a field or a ring.[7]

In this section, it is supposed that matrix entries belong to a fixed ring, which is typically a field of numbers.

Addition, scalar multiplication, subtraction and transposition

The sum Template:Math of two Template:Math matrices Template:Math and Template:Math is calculated entrywise: For example,

The product Template:Math of a number Template:Mvar (also called a scalar in this context) and a matrix Template:Math is computed by multiplying every entry of Template:Math by Template:Mvar: This operation is called scalar multiplication, but its result is not named "scalar product" to avoid confusion, since "scalar product" is often used as a synonym for "inner product". For example:

The subtraction of two Template:Math matrices is defined by composing matrix addition with scalar multiplication by Template:Math:

The transpose of an Template:Math matrix Template:Math is the Template:Math matrix Template:Math (also denoted Template:Math or Template:Math) formed by turning rows into columns and vice versa: For example:

Familiar properties of numbers extend to these operations on matrices: for example, addition is commutative, that is, the matrix sum does not depend on the order of the summands: Template:Math.[8] The transpose is compatible with addition and scalar multiplication, as expressed by Template:Math and Template:Math. Finally, Template:Math.

Matrix multiplication

Multiplication of two matrices is defined if and only if the number of columns of the left matrix is the same as the number of rows of the right matrix. If Template:Math is an Template:Math matrix and Template:Math is an Template:Math matrix, then their matrix product Template:Math is the Template:Math matrix whose entries are given by dot product of the corresponding row of Template:Math and the corresponding column of Template:Math:[9]

where Template:Math and Template:Math.[10] For example, the underlined entry 2340 in the product is calculated as Template:Math

Matrix multiplication satisfies the rules Template:Math (associativity), and Template:Math as well as Template:Math (left and right distributivity), whenever the size of the matrices is such that the various products are defined.[11] The product Template:Math may be defined without Template:Math being defined, namely if Template:Math and Template:Math are Template:Math and Template:Math matrices, respectively, and Template:Math Even if both products are defined, they generally need not be equal, that is:

In other words, matrix multiplication is not commutative, in marked contrast to (rational, real, or complex) numbers, whose product is independent of the order of the factors.[9] An example of two matrices not commuting with each other is:

whereas

Besides the ordinary matrix multiplication just described, other less frequently used operations on matrices that can be considered forms of multiplication also exist, such as the Hadamard product and the Kronecker product.[12] They arise in solving matrix equations such as the Sylvester equation.

Row operations

Template:Main There are three types of row operations:

- row addition, that is adding a row to another.

- row multiplication, that is multiplying all entries of a row by a non-zero constant;

- row switching, that is interchanging two rows of a matrix;

These operations are used in several ways, including solving linear equations and finding matrix inverses.

Template:Anchor Submatrix

A submatrix of a matrix is a matrix obtained by deleting any collection of rows and/or columns.[13][14][15] For example, from the following 3-by-4 matrix, we can construct a 2-by-3 submatrix by removing row 3 and column 2:

The minors and cofactors of a matrix are found by computing the determinant of certain submatrices.[15][16]

A principal submatrix is a square submatrix obtained by removing certain rows and columns. The definition varies from author to author. According to some authors, a principal submatrix is a submatrix in which the set of row indices that remain is the same as the set of column indices that remain.[17][18] Other authors define a principal submatrix as one in which the first Template:Mvar rows and columns, for some number Template:Mvar, are the ones that remain;[19] this type of submatrix has also been called a leading principal submatrix.[20]

Linear equations

Template:Main Matrices can be used to compactly write and work with multiple linear equations, that is, systems of linear equations. For example, if Template:Math is an Template:Math matrix, Template:Math designates a column vector (that is, Template:Math-matrix) of Template:Mvar variables Template:Math and Template:Math is an Template:Math-column vector, then the matrix equation

is equivalent to the system of linear equations[21]

Using matrices, this can be solved more compactly than would be possible by writing out all the equations separately. If Template:Math and the equations are independent, then this can be done by writing

where Template:Math is the inverse matrix of Template:Math. If Template:Math has no inverse, solutions—if any—can be found using its generalized inverse.

Linear transformations

Matrices and matrix multiplication reveal their essential features when related to linear transformations, also known as linear maps. A real Template:Mvar-by-Template:Mvar matrix Template:Math gives rise to a linear transformation mapping each vector Template:Math in Template:Tmath to the (matrix) product Template:Math, which is a vector in Template:Tmath Conversely, each linear transformation arises from a unique Template:Mvar-by-Template:Mvar matrix Template:Math: explicitly, the Template:Math-entry of Template:Math is the Template:Mvarth coordinate of Template:Math, where Template:Math is the unit vector with 1 in the Template:Mvarth position and 0 elsewhere. The matrix Template:Math is said to represent the linear map Template:Mvar, and Template:Math is called the transformation matrix of Template:Mvar.

For example, the 2×2 matrix

can be viewed as the transform of the unit square into a parallelogram with vertices at Template:Math, Template:Math, Template:Math, and Template:Math. The parallelogram pictured at the right is obtained by multiplying Template:Math with each of the column vectors , and in turn. These vectors define the vertices of the unit square.

The following table shows several 2×2 real matrices with the associated linear maps of Template:Tmath

The Template:Font color original is mapped to the Template:Font color grid and shapes. The origin Template:Math is marked with a black point.

| Horizontal shear with m = 1.25. |

Reflection through the vertical axis | Squeeze mapping with r = 3/2 |

Scaling by a factor of 3/2 |

Rotation by Template:Pi/6 = 30° |

|

|

|

|

|

Under the 1-to-1 correspondence between matrices and linear maps, matrix multiplication corresponds to composition of maps:[22] if a Template:Mvar-by-Template:Mvar matrix Template:Math represents another linear map , then the composition Template:Math is represented by Template:Math since

The last equality follows from the above-mentioned associativity of matrix multiplication.

The rank of a matrix Template:Math is the maximum number of linearly independent row vectors of the matrix, which is the same as the maximum number of linearly independent column vectors.[23] Equivalently it is the dimension of the image of the linear map represented by Template:Math.[24] The rank–nullity theorem states that the dimension of the kernel of a matrix plus the rank equals the number of columns of the matrix.[25]

Square matrix

Template:Main A square matrix is a matrix with the same number of rows and columns.[5] An Template:Mvar-by-Template:Mvar matrix is known as a square matrix of order Template:Mvar. Any two square matrices of the same order can be added and multiplied. The entries Template:Mvar form the main diagonal of a square matrix. They lie on the imaginary line that runs from the top left corner to the bottom right corner of the matrix.

Main types

Name Example with Template:Math Diagonal matrix Lower triangular matrix Upper triangular matrix

Diagonal and triangular matrix

If all entries of Template:Math below the main diagonal are zero, Template:Math is called an upper triangular matrix. Similarly, if all entries of Template:Math above the main diagonal are zero, Template:Math is called a lower triangular matrix. If all entries outside the main diagonal are zero, Template:Math is called a diagonal matrix.

Identity matrix

Template:Main The identity matrix Template:Math of size Template:Mvar is the Template:Mvar-by-Template:Mvar matrix in which all the elements on the main diagonal are equal to 1 and all other elements are equal to 0, for example, It is a square matrix of order Template:Mvar, and also a special kind of diagonal matrix. It is called an identity matrix because multiplication with it leaves a matrix unchanged: for any Template:Mvar-by-Template:Mvar matrix Template:Math.

A nonzero scalar multiple of an identity matrix is called a scalar matrix. If the matrix entries come from a field, the scalar matrices form a group, under matrix multiplication, that is isomorphic to the multiplicative group of nonzero elements of the field.

Symmetric or skew-symmetric matrix

A square matrix Template:Math that is equal to its transpose, that is, Template:Math, is a symmetric matrix. If instead, Template:Math is equal to the negative of its transpose, that is, Template:Math, then Template:Math is a skew-symmetric matrix. In complex matrices, symmetry is often replaced by the concept of Hermitian matrices, which satisfies Template:Math, where the star or asterisk denotes the conjugate transpose of the matrix, that is, the transpose of the complex conjugate of Template:Math.

By the spectral theorem, real symmetric matrices and complex Hermitian matrices have an eigenbasis; that is, every vector is expressible as a linear combination of eigenvectors. In both cases, all eigenvalues are real.[26] This theorem can be generalized to infinite-dimensional situations related to matrices with infinitely many rows and columns, see below.

Invertible matrix and its inverse

A square matrix Template:Math is called invertible or non-singular if there exists a matrix Template:Math such that[27][28] where Template:Math is the Template:Math identity matrix with 1s on the main diagonal and 0s elsewhere. If Template:Math exists, it is unique and is called the inverse matrix of Template:Math, denoted Template:Math.

There are many algorithms for testing whether a square marix is invertible, and, if it is, computing its inverse. One of the oldest, which is still in common use is Gaussian elimination.

Definite matrix

| Positive definite matrix | Indefinite matrix |

|---|---|

Points such that (Ellipse) |

Points such that (Hyperbola) |

A symmetric real matrix Template:Math is called positive-definite if the associated quadratic form has a positive value for every nonzero vector Template:Math in Template:Tmath If Template:Math only yields negative values then Template:Math is negative-definite; if Template:Mvar does produce both negative and positive values then Template:Math is indefinite.[29] If the quadratic form Template:Mvar yields only non-negative values (positive or zero), the symmetric matrix is called positive-semidefinite (or if only non-positive values, then negative-semidefinite); hence the matrix is indefinite precisely when it is neither positive-semidefinite nor negative-semidefinite.

A symmetric matrix is positive-definite if and only if all its eigenvalues are positive, that is, the matrix is positive-semidefinite and it is invertible.[30] The table at the right shows two possibilities for 2-by-2 matrices.

Allowing as input two different vectors instead yields the bilinear form associated to Template:Math:[31]

In the case of complex matrices, the same terminology and result apply, with symmetric matrix, quadratic form, bilinear form, and transpose Template:Math replaced respectively by Hermitian matrix, Hermitian form, sesquilinear form, and conjugate transpose Template:Math.

Orthogonal matrix

Template:Main An orthogonal matrix is a square matrix with real entries whose columns and rows are orthogonal unit vectors (that is, orthonormal vectors). Equivalently, a matrix Template:Math is orthogonal if its transpose is equal to its inverse:

which entails

where Template:Math is the identity matrix of size Template:Mvar.

An orthogonal matrix Template:Math is necessarily invertible (with inverse Template:Math), unitary (Template:Math), and normal (Template:Math). The determinant of any orthogonal matrix is either Template:Math or Template:Math. A special orthogonal matrix is an orthogonal matrix with determinant +1. As a linear transformation, every orthogonal matrix with determinant Template:Math is a pure rotation without reflection, i.e., the transformation preserves the orientation of the transformed structure, while every orthogonal matrix with determinant Template:Math reverses the orientation, i.e., is a composition of a pure reflection and a (possibly null) rotation. The identity matrices have determinant Template:Math and are pure rotations by an angle zero.

The complex analog of an orthogonal matrix is a unitary matrix.

Main operations

Trace

The trace, Template:Math of a square matrix Template:Math is the sum of its diagonal entries. While matrix multiplication is not commutative as mentioned above, the trace of the product of two matrices is independent of the order of the factors:

This is immediate from the definition of matrix multiplication:

It follows that the trace of the product of more than two matrices is independent of cyclic permutations of the matrices, however, this does not in general apply for arbitrary permutations (for example, Template:Math, in general). Also, the trace of a matrix is equal to that of its transpose, that is,

Determinant

The determinant of a square matrix Template:Math (denoted Template:Math or Template:Math) is a number encoding certain properties of the matrix. A matrix is invertible if and only if its determinant is nonzero. Its absolute value equals the area (in Template:Tmath) or volume (in Template:Tmath) of the image of the unit square (or cube), while its sign corresponds to the orientation of the corresponding linear map: the determinant is positive if and only if the orientation is preserved.

The determinant of 2-by-2 matrices is given by

The determinant of 3-by-3 matrices involves 6 terms (rule of Sarrus). The more lengthy Leibniz formula generalizes these two formulae to all dimensions.[33]

The determinant of a product of square matrices equals the product of their determinants: or using alternate notation:[34] Adding a multiple of any row to another row, or a multiple of any column to another column does not change the determinant. Interchanging two rows or two columns affects the determinant by multiplying it by −1.[35] Using these operations, any matrix can be transformed to a lower (or upper) triangular matrix, and for such matrices, the determinant equals the product of the entries on the main diagonal; this provides a method to calculate the determinant of any matrix. Finally, the Laplace expansion expresses the determinant in terms of minors, that is, determinants of smaller matrices.[36] This expansion can be used for a recursive definition of determinants (taking as starting case the determinant of a 1-by-1 matrix, which is its unique entry, or even the determinant of a 0-by-0 matrix, which is 1), that can be seen to be equivalent to the Leibniz formula. Determinants can be used to solve linear systems using Cramer's rule, where the division of the determinants of two related square matrices equates to the value of each of the system's variables.[37]

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

Template:Main A number and a non-zero vector Template:Math satisfying

are called an eigenvalue and an eigenvector of Template:Math, respectively.[38][39] The number Template:Mvar is an eigenvalue of an Template:Math-matrix Template:Math if and only if Template:Math is not invertible, which is equivalent to

The polynomial Template:Math in an indeterminate Template:Mvar given by evaluation of the determinant Template:Math is called the characteristic polynomial of Template:Math. It is a monic polynomial of degree Template:Mvar. Therefore the polynomial equation Template:Math has at most Template:Mvar different solutions, that is, eigenvalues of the matrix.[41] They may be complex even if the entries of Template:Math are real. According to the Cayley–Hamilton theorem, Template:Math, that is, the result of substituting the matrix itself into its characteristic polynomial yields the zero matrix.

Computational aspects

Matrix calculations can be often performed with different techniques. Many problems can be solved by both direct algorithms and iterative approaches. For example, the eigenvectors of a square matrix can be obtained by finding a sequence of vectors Template:Math converging to an eigenvector when Template:Mvar tends to infinity.[42]

To choose the most appropriate algorithm for each specific problem, it is important to determine both the effectiveness and precision of all the available algorithms. The domain studying these matters is called numerical linear algebra.[43] As with other numerical situations, two main aspects are the complexity of algorithms and their numerical stability.

Determining the complexity of an algorithm means finding upper bounds or estimates of how many elementary operations such as additions and multiplications of scalars are necessary to perform some algorithm, for example, multiplication of matrices. Calculating the matrix product of two Template:Mvar-by-Template:Mvar matrices using the definition given above needs Template:Math multiplications, since for any of the Template:Math entries of the product, Template:Mvar multiplications are necessary. The Strassen algorithm outperforms this "naive" algorithm; it needs only Template:Math multiplications.[44] A refined approach also incorporates specific features of the computing devices.

In many practical situations, additional information about the matrices involved is known. An important case is sparse matrices, that is, matrices most of whose entries are zero. There are specifically adapted algorithms for, say, solving linear systems Template:Math for sparse matrices Template:Math, such as the conjugate gradient method.[45]

An algorithm is, roughly speaking, numerically stable if little deviations in the input values do not lead to big deviations in the result. For example, calculating the inverse of a matrix via Laplace expansion (Template:Math denotes the adjugate matrix of Template:Math) may lead to significant rounding errors if the determinant of the matrix is very small. The norm of a matrix can be used to capture the conditioning of linear algebraic problems, such as computing a matrix's inverse.[46]

Most computer programming languages support arrays but are not designed with built-in commands for matrices. Instead, available external libraries provide matrix operations on arrays, in nearly all currently used programming languages. Matrix manipulation was among the earliest numerical applications of computers.[47] The original Dartmouth BASIC had built-in commands for matrix arithmetic on arrays from its second edition implementation in 1964. As early as the 1970s, some engineering desktop computers such as the HP 9830 had ROM cartridges to add BASIC commands for matrices. Some computer languages such as APL were designed to manipulate matrices, and various mathematical programs can be used to aid computing with matrices.[48] As of 2023, most computers have some form of built-in matrix operations at a low level implementing the standard BLAS specification, upon which most higher-level matrix and linear algebra libraries (e.g., EISPACK, LINPACK, LAPACK) rely. While most of these libraries require a professional level of coding, LAPACK can be accessed by higher-level (and user-friendly) bindings such as NumPy/SciPy, R, GNU Octave, MATLAB.

Decomposition

Template:Main There are several methods to render matrices into a more easily accessible form. They are generally referred to as matrix decomposition or matrix factorization techniques. The interest of all these techniques is that they preserve certain properties of the matrices in question, such as determinant, rank, or inverse, so that these quantities can be calculated after applying the transformation, or that certain matrix operations are algorithmically easier to carry out for some types of matrices.

The LU decomposition factors matrices as a product of lower (Template:Math) and an upper triangular matrices (Template:Math).[49] Once this decomposition is calculated, linear systems can be solved more efficiently, by a simple technique called forward and back substitution. Likewise, inverses of triangular matrices are algorithmically easier to calculate. The Gaussian elimination is a similar algorithm; it transforms any matrix to row echelon form.[50] Both methods proceed by multiplying the matrix by suitable elementary matrices, which correspond to permuting rows or columns and adding multiples of one row to another row. Singular value decomposition expresses any matrix Template:Math as a product Template:Math, where Template:Math and Template:Math are unitary matrices and Template:Math is a diagonal matrix.

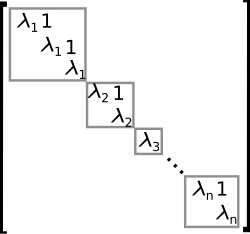

The eigendecomposition or diagonalization expresses Template:Math as a product Template:Math, where Template:Math is a diagonal matrix and Template:Math is a suitable invertible matrix.[51] If Template:Math can be written in this form, it is called diagonalizable. More generally, and applicable to all matrices, the Jordan decomposition transforms a matrix into Jordan normal form, that is to say matrices whose only nonzero entries are the eigenvalues Template:Math to Template:Mvar of Template:Math, placed on the main diagonal and possibly entries equal to one directly above the main diagonal, as shown at the right.[52] Given the eigendecomposition, the Template:Mvarth power of Template:Math (that is, Template:Mvar-fold iterated matrix multiplication) can be calculated via and the power of a diagonal matrix can be calculated by taking the corresponding powers of the diagonal entries, which is much easier than doing the exponentiation for Template:Math instead. This can be used to compute the matrix exponential Template:Math, a need frequently arising in solving linear differential equations, matrix logarithms and square roots of matrices.[53] To avoid numerically ill-conditioned situations, further algorithms such as the Schur decomposition can be employed.[54]

Abstract algebraic aspects and generalizations

Matrices can be generalized in different ways. Abstract algebra uses matrices with entries in more general fields or even rings, while linear algebra codifies properties of matrices in the notion of linear maps. It is possible to consider matrices with infinitely many columns and rows. Another extension is tensors, which can be seen as higher-dimensional arrays of numbers, as opposed to vectors, which can often be realized as sequences of numbers, while matrices are rectangular or two-dimensional arrays of numbers.[55] Matrices, subject to certain requirements tend to form groups known as matrix groups. Similarly under certain conditions matrices form rings known as matrix rings. Though the product of matrices is not in general commutative certain matrices form fields known as matrix fields. In general, matrices and their multiplication also form a category, the category of matrices.

Matrices with more general entries

This article focuses on matrices whose entries are real or complex numbers. However, matrices can be considered with much more general types of entries than real or complex numbers. As a first step of generalization, any field, that is, a set where addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division operations are defined and well-behaved, may be used instead of Template:Tmath or Template:Tmath for example rational numbers or finite fields. For example, coding theory makes use of matrices over finite fields. Wherever eigenvalues are considered, as these are roots of a polynomial they may exist only in a larger field than that of the entries of the matrix; for instance, they may be complex in the case of a matrix with real entries. The possibility to reinterpret the entries of a matrix as elements of a larger field (for example, to view a real matrix as a complex matrix whose entries happen to be all real) then allows considering each square matrix to possess a full set of eigenvalues. Alternatively one can consider only matrices with entries in an algebraically closed field, such as Template:Tmath from the outset.

More generally, matrices with entries in a ring Template:Mvar are widely used in mathematics.[56] Rings are a more general notion than fields in that a division operation need not exist. The very same addition and multiplication operations of matrices extend to this setting, too. The set Template:Math (also denoted Template:Math[57]) of all square Template:Mvar-by-Template:Mvar matrices over Template:Mvar is a ring called matrix ring, isomorphic to the endomorphism ring of the left Template:Mvar-module Template:Mvar.[58] If the ring Template:Mvar is commutative, that is, its multiplication is commutative, then the ring Template:Math is also an associative algebra over R. The determinant of square matrices over a commutative ring Template:Mvar can still be defined using the Leibniz formula; such a matrix is invertible if and only if its determinant is invertible in Template:Mvar, generalizing the situation over a field Template:Mvar, where every nonzero element is invertible.[59] Matrices over superrings are called supermatrices.[60]

Matrices do not always have all their entries in the same ringTemplate:Nbsp– or even in any ring at all. One special but common case is block matrices, which may be considered as matrices whose entries themselves are matrices. The entries need not be square matrices, and thus need not be members of any ring; but their sizes must fulfill certain compatibility conditions.

Relationship to linear maps

Linear maps are equivalent to Template:Mvar-by-Template:Mvar matrices, as described above. More generally, any linear map Template:Math between finite-dimensional vector spaces can be described by a matrix Template:Math, after choosing bases Template:Math of Template:Mvar, and Template:Math of Template:Mvar (so Template:Mvar is the dimension of Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar is the dimension of Template:Mvar), which is such that

In other words, column Template:Mvar of Template:Math expresses the image of Template:Math in terms of the basis vectors Template:Math of Template:Mvar; thus this relation uniquely determines the entries of the matrix Template:Math. The matrix depends on the choice of the bases: different choices of bases give rise to different, but equivalent matrices.[61] Many of the above concrete notions can be reinterpreted in this light, for example, the transpose matrix Template:Math describes the transpose of the linear map given by Template:Math, concerning the dual bases.[62]

These properties can be restated more naturally: the category of matrices with entries in a field with multiplication as composition is equivalent to the category of finite-dimensional vector spaces and linear maps over this field.[63]

More generally, the set of Template:Math matrices can be used to represent the Template:Mvar-linear maps between the free modules Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar for an arbitrary ring Template:Mvar with unity. When Template:Math composition of these maps is possible, and this gives rise to the matrix ring of Template:Math matrices representing the endomorphism ring of Template:Mvar.

Matrix groups

Template:Main A group is a mathematical structure consisting of a set of objects together with a binary operation, that is, an operation combining any two objects to a third, subject to certain requirements.[64] A group in which the objects are matrices and the group operation is matrix multiplication is called a matrix group.[65][66] Since a group of every element must be invertible, the most general matrix groups are the groups of all invertible matrices of a given size, called the general linear groups.

Any property of matrices that is preserved under matrix products and inverses can be used to define further matrix groups. For example, matrices with a given size and with a determinant of 1 form a subgroup of (that is, a smaller group contained in) their general linear group, called a special linear group.[67] Orthogonal matrices, determined by the condition form the orthogonal group.[68] Every orthogonal matrix has determinant 1 or −1. Orthogonal matrices with determinant 1 form a subgroup called special orthogonal group.

Every finite group is isomorphic to a matrix group, as one can see by considering the regular representation of the symmetric group.[69] General groups can be studied using matrix groups, which are comparatively well understood, using representation theory.[70]

Infinite matrices

It is also possible to consider matrices with infinitely many rows and/or columns[71] even though, being infinite objects, one cannot write down such matrices explicitly. All that matters is that for every element in the set indexing rows, and every element in the set indexing columns, there is a well-defined entry (these index sets need not even be subsets of the natural numbers). The basic operations of addition, subtraction, scalar multiplication, and transposition can still be defined without problem; however, matrix multiplication may involve infinite summations to define the resulting entries, and these are not defined in general.

If Template:Mvar is any ring with unity, then the ring of endomorphisms of as a right Template:Mvar module is isomorphic to the ring of column finite matrices whose entries are indexed by , and whose columns each contain only finitely many nonzero entries. The endomorphisms of Template:Mvar considered as a left Template:Mvar module result in an analogous object, the row finite matrices whose rows each only have finitely many nonzero entries.

If infinite matrices are used to describe linear maps, then only those matrices can be used all of whose columns have but a finite number of nonzero entries, for the following reason. For a matrix Template:Math to describe a linear map Template:Math, bases for both spaces must have been chosen; recall that by definition this means that every vector in the space can be written uniquely as a (finite) linear combination of basis vectors, so that written as a (column) vectorTemplate:NbspTemplate:Mvar of coefficients, only finitely many entries Template:Mvar are nonzero. Now the columns of Template:Math describe the images by Template:Mvar of individual basis vectors of Template:Mvar in the basis of Template:Mvar, which is only meaningful if these columns have only finitely many nonzero entries. There is no restriction on the rows of Template:Math however: in the product Template:Math there are only finitely many nonzero coefficients of Template:Mvar involved, so every one of its entries, even if it is given as an infinite sum of products, involves only finitely many nonzero terms and is therefore well defined. Moreover, this amounts to forming a linear combination of the columns of Template:Math that effectively involves only finitely many of them, whence the result has only finitely many nonzero entries because each of those columns does. Products of two matrices of the given type are well defined (provided that the column-index and row-index sets match), are of the same type, and correspond to the composition of linear maps.

If Template:Mvar is a normed ring, then the condition of row or column finiteness can be relaxed. With the norm in place, absolutely convergent series can be used instead of finite sums. For example, the matrices whose column sums are convergent sequences form a ring. Analogously, the matrices whose row sums are convergent series also form a ring.

Infinite matrices can also be used to describe operators on Hilbert spaces, where convergence and continuity questions arise, which again results in certain constraints that must be imposed. However, the explicit point of view of matrices tends to obfuscate the matter,[72] and the abstract and more powerful tools of functional analysis can be used instead.

Empty matrix

An empty matrix is a matrix in which the number of rows or columns (or both) is zero.[73][74] Empty matrices help to deal with maps involving the zero vector space. For example, if Template:Math is a 3-by-0 matrix and Template:Math is a 0-by-3 matrix, then Template:Math is the 3-by-3 zero matrix corresponding to the null map from a 3-dimensional space Template:Mvar to itself, while Template:Math is a 0-by-0 matrix. There is no common notation for empty matrices, but most computer algebra systems allow creating and computing with them. The determinant of the 0-by-0 matrix is 1 as follows regarding the empty product occurring in the Leibniz formula for the determinant as 1. This value is also consistent with the fact that the identity map from any finite-dimensional space to itself has determinantTemplate:Nbsp1, a fact that is often used as a part of the characterization of determinants.

Applications

There are numerous applications of matrices, both in mathematics and other sciences. Some of them merely take advantage of the compact representation of a set of numbers in a matrix. For example, in game theory and economics, the payoff matrix encodes the payoff for two players, depending on which out of a given (finite) set of strategies the players choose.[75] Text mining and automated thesaurus compilation makes use of document-term matrices such as tf-idf to track frequencies of certain words in several documents.[76]

Complex numbers can be represented by particular real 2-by-2 matrices via

under which addition and multiplication of complex numbers and matrices correspond to each other. For example, 2-by-2 rotation matrices represent the multiplication with some complex number of absolute value 1, as above. A similar interpretation is possible for quaternions[77] and Clifford algebras in general.

Early encryption techniques such as the Hill cipher also used matrices. However, due to the linear nature of matrices, these codes are comparatively easy to break.[78] Computer graphics uses matrices to represent objects; to calculate transformations of objects using affine rotation matrices to accomplish tasks such as projecting a three-dimensional object onto a two-dimensional screen, corresponding to a theoretical camera observation; and to apply image convolutions such as sharpening, blurring, edge detection, and more.[79] Matrices over a polynomial ring are important in the study of control theory.

Chemistry makes use of matrices in various ways, particularly since the use of quantum theory to discuss molecular bonding and spectroscopy. Examples are the overlap matrix and the Fock matrix used in solving the Roothaan equations to obtain the molecular orbitals of the Hartree–Fock method.

Graph theory

The adjacency matrix of a finite graph is a basic notion of graph theory.[80] It records which vertices of the graph are connected by an edge. Matrices containing just two different values (1 and 0 meaning for example "yes" and "no", respectively) are called logical matrices. The distance (or cost) matrix contains information about the distances of the edges.[81] These concepts can be applied to websites connected by hyperlinks or cities connected by roads etc., in which case (unless the connection network is extremely dense) the matrices tend to be sparse, that is, contain few nonzero entries. Therefore, specifically tailored matrix algorithms can be used in network theory.

Analysis and geometry

The Hessian matrix of a differentiable function consists of the second derivatives of Template:Mvar concerning the several coordinate directions, that is,[82]

It encodes information about the local growth behavior of the function: given a critical point Template:Math, that is, a point where the first partial derivatives

of Template:Mvar vanish, the function has a local minimum if the Hessian matrix is positive definite. Quadratic programming can be used to find global minima or maxima of quadratic functions closely related to the ones attached to matrices (see above).[83]

Another matrix frequently used in geometrical situations is the Jacobi matrix of a differentiable map If Template:Math denote the components of Template:Mvar, then the Jacobi matrix is defined as[84]

If Template:Math, and if the rank of the Jacobi matrix attains its maximal value Template:Mvar, Template:Mvar is locally invertible at that point, by the implicit function theorem.[85]

Partial differential equations can be classified by considering the matrix of coefficients of the highest-order differential operators of the equation. For elliptic partial differential equations this matrix is positive definite, which has a decisive influence on the set of possible solutions of the equation in question.[86]

The finite element method is an important numerical method to solve partial differential equations, widely applied in simulating complex physical systems. It attempts to approximate the solution to some equation by piecewise linear functions, where the pieces are chosen concerning a sufficiently fine grid, which in turn can be recast as a matrix equation.[87]

Probability theory and statistics

Stochastic matrices are square matrices whose rows are probability vectors, that is, whose entries are non-negative and sum up to one. Stochastic matrices are used to define Markov chains with finitely many states.[88] A row of the stochastic matrix gives the probability distribution for the next position of some particle currently in the state that corresponds to the row. Properties of the Markov chain-like absorbing states, that is, states that any particle attains eventually, can be read off the eigenvectors of the transition matrices.[89]

Statistics also makes use of matrices in many different forms.[90] Descriptive statistics is concerned with describing data sets, which can often be represented as data matrices, which may then be subjected to dimensionality reduction techniques. The covariance matrix encodes the mutual variance of several random variables.[91] Another technique using matrices are linear least squares, a method that approximates a finite set of pairs Template:Math, by a linear function

which can be formulated in terms of matrices, related to the singular value decomposition of matrices.[92]

Random matrices are matrices whose entries are random numbers, subject to suitable probability distributions, such as matrix normal distribution. Beyond probability theory, they are applied in domains ranging from number theory to physics.[93][94]

Symmetries and transformations in physics

Template:Further Linear transformations and the associated symmetries play a key role in modern physics. For example, elementary particles in quantum field theory are classified as representations of the Lorentz group of special relativity and, more specifically, by their behavior under the spin group. Concrete representations involving the Pauli matrices and more general gamma matrices are an integral part of the physical description of fermions, which behave as spinors.[95] For the three lightest quarks, there is a group-theoretical representation involving the special unitary group SU(3); for their calculations, physicists use a convenient matrix representation known as the Gell-Mann matrices, which are also used for the SU(3) gauge group that forms the basis of the modern description of strong nuclear interactions, quantum chromodynamics. The Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa matrix, in turn, expresses the fact that the basic quark states that are important for weak interactions are not the same as, but linearly related to the basic quark states that define particles with specific and distinct masses.[96]

Linear combinations of quantum states

The first model of quantum mechanics (Heisenberg, 1925) represented the theory's operators by infinite-dimensional matrices acting on quantum states.[97] This is also referred to as matrix mechanics. One particular example is the density matrix that characterizes the "mixed" state of a quantum system as a linear combination of elementary, "pure" eigenstates.[98]

Another matrix serves as a key tool for describing the scattering experiments that form the cornerstone of experimental particle physics: Collision reactions such as occur in particle accelerators, where non-interacting particles head towards each other and collide in a small interaction zone, with a new set of non-interacting particles as the result, can be described as the scalar product of outgoing particle states and a linear combination of ingoing particle states. The linear combination is given by a matrix known as the S-matrix, which encodes all information about the possible interactions between particles.[99]

Normal modes

A general application of matrices in physics is the description of linearly coupled harmonic systems. The equations of motion of such systems can be described in matrix form, with a mass matrix multiplying a generalized velocity to give the kinetic term, and a force matrix multiplying a displacement vector to characterize the interactions. The best way to obtain solutions is to determine the system's eigenvectors, its normal modes, by diagonalizing the matrix equation. Techniques like this are crucial when it comes to the internal dynamics of molecules: the internal vibrations of systems consisting of mutually bound component atoms.[100] They are also needed for describing mechanical vibrations, and oscillations in electrical circuits.[101]

Geometrical optics

Geometrical optics provides further matrix applications. In this approximative theory, the wave nature of light is neglected. The result is a model in which light rays are indeed geometrical rays. If the deflection of light rays by optical elements is small, the action of a lens or reflective element on a given light ray can be expressed as multiplication of a two-component vector with a two-by-two matrix called ray transfer matrix analysis: the vector's components are the light ray's slope and its distance from the optical axis, while the matrix encodes the properties of the optical element. There are two kinds of matrices, viz. a refraction matrix describing the refraction at a lens surface, and a translation matrix, describing the translation of the plane of reference to the next refracting surface, where another refraction matrix applies. The optical system, consisting of a combination of lenses and/or reflective elements, is simply described by the matrix resulting from the product of the components' matrices.[102]

Electronics

Traditional mesh analysis and nodal analysis in electronics lead to a system of linear equations that can be described with a matrix.

The behavior of many electronic components can be described using matrices. Let Template:Mvar be a 2-dimensional vector with the component's input voltage Template:Math and input current Template:Math as its elements, and let Template:Mvar be a 2-dimensional vector with the component's output voltage Template:Math and output current Template:Math as its elements. Then the behavior of the electronic component can be described by Template:Math, where Template:Mvar is a 2 x 2 matrix containing one impedance element (Template:Mvar), one admittance element (Template:Mvar), and two dimensionless elements (Template:Math and Template:Math). Calculating a circuit now reduces to multiplying matrices.

History

Matrices have a long history of application in solving linear equations but they were known as arrays until the 1800s. The Chinese text The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art written in the 10th–2nd century BCE is the first example of the use of array methods to solve simultaneous equations,[103] including the concept of determinants. In 1545 Italian mathematician Gerolamo Cardano introduced the method to Europe when he published Ars Magna.[104] The Japanese mathematician Seki used the same array methods to solve simultaneous equations in 1683.[105] The Dutch mathematician Jan de Witt represented transformations using arrays in his 1659 book Elements of Curves (1659).[106] Between 1700 and 1710 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz publicized the use of arrays for recording information or solutions and experimented with over 50 different systems of arrays.[104] Cramer presented his rule in 1750.

The term "matrix" (Latin for "womb", "dam" (non-human female animal kept for breeding), "source", "origin", "list", and "register", are derived from mater—mother[107]) was coined by James Joseph Sylvester in 1850,[108] who understood a matrix as an object giving rise to several determinants today called minors, that is to say, determinants of smaller matrices that derive from the original one by removing columns and rows. In an 1851 paper, Sylvester explains:[109]

Arthur Cayley published a treatise on geometric transformations using matrices that were not rotated versions of the coefficients being investigated as had previously been done. Instead, he defined operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division as transformations of those matrices and showed the associative and distributive properties held. Cayley investigated and demonstrated the non-commutative property of matrix multiplication as well as the commutative property of matrix addition.[104] Early matrix theory had limited the use of arrays almost exclusively to determinants and Arthur Cayley's abstract matrix operations were revolutionary. He was instrumental in proposing a matrix concept independent of equation systems. In 1858 Cayley published his A memoir on the theory of matrices[110][111] in which he proposed and demonstrated the Cayley–Hamilton theorem.[104]

The English mathematician Cuthbert Edmund Cullis was the first to use modern bracket notation for matrices in 1913 and he simultaneously demonstrated the first significant use of the notation Template:Math to represent a matrix where Template:Mvar refers to the Template:Mvarth row and the Template:Mvarth column.[104]

The modern study of determinants sprang from several sources.[112] Number-theoretical problems led Gauss to relate coefficients of quadratic forms, that is, expressions such as Template:Math and linear maps in three dimensions to matrices. Eisenstein further developed these notions, including the remark that, in modern parlance, matrix products are non-commutative. Cauchy was the first to prove general statements about determinants, using as the definition of the determinant of a matrix Template:Math the following: replace the powers Template:Mvar by Template:Mvar in the polynomial

- ,

where denotes the product of the indicated terms. He also showed, in 1829, that the eigenvalues of symmetric matrices are real.[113] Jacobi studied "functional determinants"—later called Jacobi determinants by Sylvester—which can be used to describe geometric transformations at a local (or infinitesimal) level, see above. Kronecker's Vorlesungen über die Theorie der Determinanten[114] and Weierstrass' Zur Determinantentheorie,[115] both published in 1903, first treated determinants axiomatically, as opposed to previous more concrete approaches such as the mentioned formula of Cauchy. At that point, determinants were firmly established.

Many theorems were first established for small matrices only, for example, the Cayley–Hamilton theorem was proved for 2×2 matrices by Cayley in the aforementioned memoir, and by Hamilton for 4×4 matrices. Frobenius, working on bilinear forms, generalized the theorem to all dimensions (1898). Also at the end of the 19th century, the Gauss–Jordan elimination (generalizing a special case now known as Gauss elimination) was established by Wilhelm Jordan. In the early 20th century, matrices attained a central role in linear algebra,[116] partially due to their use in the classification of the hypercomplex number systems of the previous century.

The inception of matrix mechanics by Heisenberg, Born and Jordan led to studying matrices with infinitely many rows and columns.[117] Later, von Neumann carried out the mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics, by further developing functional analytic notions such as linear operators on Hilbert spaces, which, very roughly speaking, correspond to Euclidean space, but with an infinity of independent directions.

Other historical usages of the word "matrix" in mathematics

The word has been used in unusual ways by at least two authors of historical importance.

Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead in their Principia Mathematica (1910–1913) use the word "matrix" in the context of their axiom of reducibility. They proposed this axiom as a means to reduce any function to one of lower type, successively, so that at the "bottom" (0 order) the function is identical to its extension:[118]

For example, a function Template:Math of two variables Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar can be reduced to a collection of functions of a single variable, for example, Template:Mvar, by "considering" the function for all possible values of "individuals" Template:Mvar substituted in place of a variable Template:Mvar. And then the resulting collection of functions of the single variable Template:Mvar, that is, Template:Math, can be reduced to a "matrix" of values by "considering" the function for all possible values of "individuals" Template:Mvar substituted in place of variable Template:Mvar:

Alfred Tarski in his 1946 Introduction to Logic used the word "matrix" synonymously with the notion of truth table as used in mathematical logic.[119]

See also

Template:Portal Template:Div col

- List of named matrices

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Irregular matrix

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Matrix multiplication algorithm

- Tensor — A generalization of matrices with any number of indices

- Template:Annotated link

- Category of matrices — The algebraic structure formed by matrices and their multiplication

Notes

Template:Reflist Template:Reflist

References

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation.

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Lang Algebra

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

Physics references

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

Historical references

- A. Cayley A memoir on the theory of matrices. Phil. Trans. 148 1858 17–37; Math. Papers II 475–496

- Template:Citation, reprint of the 1907 original edition

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

Further reading

External links

- MacTutor: Matrices and determinants

- Matrices and Linear Algebra on the Earliest Uses Pages

- Earliest Uses of Symbols for Matrices and Vectors

Template:Linear algebra Template:Tensors Template:Authority control

- ↑ However, in the case of adjacency matrices, matrix multiplication or a variant of it allows the simultaneous computation of the number of paths between any two vertices, and of the shortest length of a path between two vertices.

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvtxt

- ↑ Template:Harvtxt

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvtxt

- ↑ Template:Harvtxt

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Template:Harvtxt

- ↑ Template:Harvtxt

- ↑ Template:Citation.

- ↑ Template:Citation.

- ↑ Template:Citation.

- ↑ Template:Citation.

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Eigen means "own" in German and in Dutch.

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ For example, Mathematica, see Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedPop-Furdui - ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvp

- ↑ See any standard reference in a group.

- ↑ Additionally, the group must be closed in the general linear group.

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ See any reference in representation theory or group representation.

- ↑ See the item "Matrix" in Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ "Not much of matrix theory carries over to infinite-dimensional spaces, and what does is not so useful, but it sometimes helps." Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ "Empty Matrix: A matrix is empty if either its row or column dimension is zero", Glossary Template:Webarchive, O-Matrix v6 User Guide

- ↑ "A matrix having at least one dimension equal to zero is called an empty matrix", MATLAB Data Structures Template:Webarchive

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations. For a more advanced, and more general statement see Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations. See also stiffness method.

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ see Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations cited by Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 104.2 104.3 104.4 Discrete Mathematics 4th Ed. Dossey, Otto, Spense, Vanden Eynden, Published by Addison Wesley, October 10, 2001 Template:ISBN, p. 564-565

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Discrete Mathematics 4th Ed. Dossey, Otto, Spense, Vanden Eynden, Published by Addison Wesley, October 10, 2001 Template:ISBN, p. 564

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Although many sources state that J. J. Sylvester coined the mathematical term "matrix" in 1848, Sylvester published nothing in 1848. (For proof that Sylvester published nothing in 1848, see J. J. Sylvester with H. F. Baker, ed., The Collected Mathematical Papers of James Joseph Sylvester (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press, 1904), vol. 1.) His earliest use of the term "matrix" occurs in 1850 in J. J. Sylvester (1850) "Additions to the articles in the September number of this journal, "On a new class of theorems," and on Pascal's theorem," The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 37: 363-370. From page 369: "For this purpose, we must commence, not with a square, but with an oblong arrangement of terms consisting, suppose, of m lines and n columns. This does not in itself represent a determinant, but is, as it were, a Matrix out of which we may form various systems of determinants ... "

- ↑ The Collected Mathematical Papers of James Joseph Sylvester: 1837–1853, Paper 37, p. 247

- ↑ Phil.Trans. 1858, vol.148, pp.17-37 Math. Papers II 475-496

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Template:Harvard citations

- ↑ Whitehead, Alfred North; and Russell, Bertrand (1913) Principia Mathematica to *56, Cambridge at the University Press, Cambridge UK (republished 1962) cf page 162ff.

- ↑ Tarski, Alfred; (1946) Introduction to Logic and the Methodology of Deductive Sciences, Dover Publications, Inc, New York NY, Template:ISBN.