Simplex: Difference between revisions

imported>Sgconlaw Applied {{Wiktionary}} |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 16:08, 24 February 2025

Template:Other uses Template:Short description

In geometry, a simplex (plural: simplexes or simplices) is a generalization of the notion of a triangle or tetrahedron to arbitrary dimensions. The simplex is so-named because it represents the simplest possible polytope in any given dimension. For example,

- a 0-dimensional simplex is a point,

- a 1-dimensional simplex is a line segment,

- a 2-dimensional simplex is a triangle,

- a 3-dimensional simplex is a tetrahedron, and

- a 4-dimensional simplex is a 5-cell.

Specifically, a Template:Mvar-simplex is a Template:Mvar-dimensional polytope that is the convex hull of its Template:Math vertices. More formally, suppose the Template:Math points are affinely independent, which means that the Template:Mvar vectors are linearly independent. Then, the simplex determined by them is the set of points

A regular simplex[1] is a simplex that is also a regular polytope. A regular Template:Mvar-simplex may be constructed from a regular Template:Math-simplex by connecting a new vertex to all original vertices by the common edge length.

The standard simplex or probability simplex[2] is the Template:Math-dimensional simplex whose vertices are the Template:Mvar standard unit vectors in , or in other words

In topology and combinatorics, it is common to "glue together" simplices to form a simplicial complex.

The geometric simplex and simplicial complex should not be confused with the abstract simplicial complex, in which a simplex is simply a finite set and the complex is a family of such sets that is closed under taking subsets.

History

The concept of a simplex was known to William Kingdon Clifford, who wrote about these shapes in 1886 but called them "prime confines". Henri Poincaré, writing about algebraic topology in 1900, called them "generalized tetrahedra". In 1902 Pieter Hendrik Schoute described the concept first with the Latin superlative simplicissimum ("simplest") and then with the same Latin adjective in the normal form simplex ("simple").[3]

The regular simplex family is the first of three regular polytope families, labeled by Donald Coxeter as Template:Math, the other two being the cross-polytope family, labeled as Template:Math, and the hypercubes, labeled as Template:Math. A fourth family, the [[hypercubic honeycomb|tessellation of Template:Mvar-dimensional space by infinitely many hypercubes]], he labeled as Template:Math.Template:Sfn

Elements

The convex hull of any nonempty subset of the Template:Math points that define an Template:Mvar-simplex is called a face of the simplex. Faces are simplices themselves. In particular, the convex hull of a subset of size Template:Math (of the Template:Math defining points) is an Template:Mvar-simplex, called an Template:Mvar-face of the Template:Mvar-simplex. The 0-faces (i.e., the defining points themselves as sets of size 1) are called the vertices (singular: vertex), the 1-faces are called the edges, the (Template:Math)-faces are called the facets, and the sole Template:Mvar-face is the whole Template:Mvar-simplex itself. In general, the number of Template:Mvar-faces is equal to the binomial coefficient .Template:Sfn Consequently, the number of Template:Mvar-faces of an Template:Mvar-simplex may be found in column (Template:Math) of row (Template:Math) of Pascal's triangle. A simplex Template:Mvar is a coface of a simplex Template:Mvar if Template:Mvar is a face of Template:Mvar. Face and facet can have different meanings when describing types of simplices in a simplicial complex.

The extended f-vector for an Template:Mvar-simplex can be computed by Template:Math, like the coefficients of polynomial products. For example, a 7-simplex is (1,1)8 = (1,2,1)4 = (1,4,6,4,1)2 = (1,8,28,56,70,56,28,8,1).

The number of 1-faces (edges) of the Template:Mvar-simplex is the Template:Mvar-th triangle number, the number of 2-faces of the Template:Mvar-simplex is the Template:Mathth tetrahedron number, the number of 3-faces of the Template:Mvar-simplex is the Template:Mathth 5-cell number, and so on.

| Template:Math | Name | Schläfli Coxeter |

0- faces (vertices) |

1- faces (edges) |

2- faces (faces) |

3- faces (cells) |

4- faces |

5- faces |

6- faces |

7- faces |

8- faces |

9- faces |

10- faces |

Sum = 2n+1 − 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ0 | 0-simplex (point) |

( ) Template:CDD |

1 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Δ1 | 1-simplex (line segment) |

{ } = ( ) ∨ ( ) = 2⋅( ) Template:CDD |

2 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||

| Δ2 | 2-simplex (triangle) |

{3} = 3⋅( ) Template:CDD |

3 | 3 | 1 | 7 | ||||||||

| Δ3 | 3-simplex (tetrahedron) |

{3,3} = 4⋅( ) Template:CDD |

4 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 15 | |||||||

| Δ4 | 4-simplex (5-cell) |

{33} = 5⋅( ) Template:CDD |

5 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 31 | ||||||

| Δ5 | 5-simplex | {34} = 6⋅( ) Template:CDD |

6 | 15 | 20 | 15 | 6 | 1 | 63 | |||||

| Δ6 | 6-simplex | {35} = 7⋅( ) Template:CDD |

7 | 21 | 35 | 35 | 21 | 7 | 1 | 127 | ||||

| Δ7 | 7-simplex | {36} = 8⋅( ) Template:CDD |

8 | 28 | 56 | 70 | 56 | 28 | 8 | 1 | 255 | |||

| Δ8 | 8-simplex | {37} = 9⋅( ) Template:CDD |

9 | 36 | 84 | 126 | 126 | 84 | 36 | 9 | 1 | 511 | ||

| Δ9 | 9-simplex | {38} = 10⋅( ) Template:CDD |

10 | 45 | 120 | 210 | 252 | 210 | 120 | 45 | 10 | 1 | 1023 | |

| Δ10 | 10-simplex | {39} = 11⋅( ) Template:CDD |

11 | 55 | 165 | 330 | 462 | 462 | 330 | 165 | 55 | 11 | 1 | 2047 |

An Template:Mvar-simplex is the polytope with the fewest vertices that requires Template:Mvar dimensions. Consider a line segment AB as a shape in a 1-dimensional space (the 1-dimensional space is the line in which the segment lies). One can place a new point Template:Mvar somewhere off the line. The new shape, triangle ABC, requires two dimensions; it cannot fit in the original 1-dimensional space. The triangle is the 2-simplex, a simple shape that requires two dimensions. Consider a triangle ABC, a shape in a 2-dimensional space (the plane in which the triangle resides). One can place a new point Template:Mvar somewhere off the plane. The new shape, tetrahedron ABCD, requires three dimensions; it cannot fit in the original 2-dimensional space. The tetrahedron is the 3-simplex, a simple shape that requires three dimensions. Consider tetrahedron ABCD, a shape in a 3-dimensional space (the 3-space in which the tetrahedron lies). One can place a new point Template:Mvar somewhere outside the 3-space. The new shape ABCDE, called a 5-cell, requires four dimensions and is called the 4-simplex; it cannot fit in the original 3-dimensional space. (It also cannot be visualized easily.) This idea can be generalized, that is, adding a single new point outside the currently occupied space, which requires going to the next higher dimension to hold the new shape. This idea can also be worked backward: the line segment we started with is a simple shape that requires a 1-dimensional space to hold it; the line segment is the 1-simplex. The line segment itself was formed by starting with a single point in 0-dimensional space (this initial point is the 0-simplex) and adding a second point, which required the increase to 1-dimensional space.

More formally, an Template:Math-simplex can be constructed as a join (∨ operator) of an Template:Mvar-simplex and a point, Template:Math. An Template:Math-simplex can be constructed as a join of an Template:Mvar-simplex and an Template:Mvar-simplex. The two simplices are oriented to be completely normal from each other, with translation in a direction orthogonal to both of them. A 1-simplex is the join of two points: Template:Math. A general 2-simplex (scalene triangle) is the join of three points: Template:Math. An isosceles triangle is the join of a 1-simplex and a point: Template:Math. An equilateral triangle is 3 ⋅ ( ) or {3}. A general 3-simplex is the join of 4 points: Template:Math. A 3-simplex with mirror symmetry can be expressed as the join of an edge and two points: Template:Math. A 3-simplex with triangular symmetry can be expressed as the join of an equilateral triangle and 1 point: Template:Math or Template:Math. A regular tetrahedron is Template:Math or Template:Mset and so on.

|

|

In some conventions,[5] the empty set is defined to be a (−1)-simplex. The definition of the simplex above still makes sense if Template:Math. This convention is more common in applications to algebraic topology (such as simplicial homology) than to the study of polytopes. Template:Clear

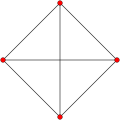

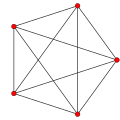

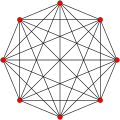

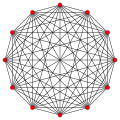

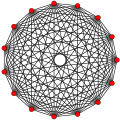

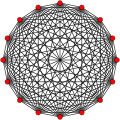

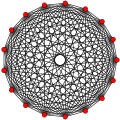

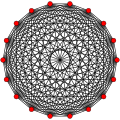

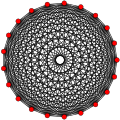

Symmetric graphs of regular simplices

These Petrie polygons (skew orthogonal projections) show all the vertices of the regular simplex on a circle, and all vertex pairs connected by edges.

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

16 |

17 |

18 |

19 |

20 |

Standard simplex

The standard Template:Mvar-simplex (or unit Template:Mvar-simplex) is the subset of Template:Math given by

- .

The simplex Template:Math lies in the affine hyperplane obtained by removing the restriction Template:Math in the above definition.

The Template:Math vertices of the standard Template:Mvar-simplex are the points Template:Math, where

A standard simplex is an example of a 0/1-polytope, with all coordinates as 0 or 1. It can also be seen one facet of a regular Template:Math-orthoplex.

There is a canonical map from the standard Template:Mvar-simplex to an arbitrary Template:Mvar-simplex with vertices (Template:Math, ..., Template:Math) given by

The coefficients Template:Math are called the barycentric coordinates of a point in the Template:Mvar-simplex. Such a general simplex is often called an affine Template:Mvar-simplex, to emphasize that the canonical map is an affine transformation. It is also sometimes called an oriented affine Template:Mvar-simplex to emphasize that the canonical map may be orientation preserving or reversing.

More generally, there is a canonical map from the standard -simplex (with Template:Mvar vertices) onto any polytope with Template:Mvar vertices, given by the same equation (modifying indexing):

These are known as generalized barycentric coordinates, and express every polytope as the image of a simplex:

A commonly used function from Template:Math to the interior of the standard -simplex is the softmax function, or normalized exponential function; this generalizes the standard logistic function.

Examples

- Δ0 is the point Template:Math in Template:Math.

- Δ1 is the line segment joining Template:Math and Template:Math in Template:Math.

- Δ2 is the equilateral triangle with vertices Template:Math, Template:Math and Template:Math in Template:Math.

- Δ3 is the regular tetrahedron with vertices Template:Math, Template:Math, Template:Math and Template:Math in Template:Math.

- Δ4 is the regular 5-cell with vertices Template:Math, Template:Math, Template:Math, Template:Math and Template:Math in Template:Math.

Increasing coordinates

An alternative coordinate system is given by taking the indefinite sum:

This yields the alternative presentation by order, namely as nondecreasing Template:Mvar-tuples between 0 and 1:

Geometrically, this is an Template:Mvar-dimensional subset of (maximal dimension, codimension 0) rather than of (codimension 1). The facets, which on the standard simplex correspond to one coordinate vanishing, here correspond to successive coordinates being equal, while the interior corresponds to the inequalities becoming strict (increasing sequences).

A key distinction between these presentations is the behavior under permuting coordinates – the standard simplex is stabilized by permuting coordinates, while permuting elements of the "ordered simplex" do not leave it invariant, as permuting an ordered sequence generally makes it unordered. Indeed, the ordered simplex is a (closed) fundamental domain for the action of the symmetric group on the Template:Mvar-cube, meaning that the orbit of the ordered simplex under the Template:Mvar! elements of the symmetric group divides the Template:Mvar-cube into mostly disjoint simplices (disjoint except for boundaries), showing that this simplex has volume Template:Math. Alternatively, the volume can be computed by an iterated integral, whose successive integrands are 1, Template:Mvar, Template:Math, Template:Math, ..., Template:Math.

A further property of this presentation is that it uses the order but not addition, and thus can be defined in any dimension over any ordered set, and for example can be used to define an infinite-dimensional simplex without issues of convergence of sums.

Projection onto the standard simplex

Especially in numerical applications of probability theory a projection onto the standard simplex is of interest. Given with possibly negative entries, the closest point on the simplex has coordinates

where is chosen such that

can be easily calculated from sorting Template:Math.[6] The sorting approach takes complexity, which can be improved to Template:Math complexity via median-finding algorithms.[7] Projecting onto the simplex is computationally similar to projecting onto the ball.

Corner of cube

Finally, a simple variant is to replace "summing to 1" with "summing to at most 1"; this raises the dimension by 1, so to simplify notation, the indexing changes:

This yields an Template:Mvar-simplex as a corner of the Template:Mvar-cube, and is a standard orthogonal simplex. This is the simplex used in the simplex method, which is based at the origin, and locally models a vertex on a polytope with Template:Mvar facets.

Cartesian coordinates for a regular Template:Mvar-dimensional simplex in Rn

One way to write down a regular Template:Mvar-simplex in Template:Math is to choose two points to be the first two vertices, choose a third point to make an equilateral triangle, choose a fourth point to make a regular tetrahedron, and so on. Each step requires satisfying equations that ensure that each newly chosen vertex, together with the previously chosen vertices, forms a regular simplex. There are several sets of equations that can be written down and used for this purpose. These include the equality of all the distances between vertices; the equality of all the distances from vertices to the center of the simplex; the fact that the angle subtended through the new vertex by any two previously chosen vertices is ; and the fact that the angle subtended through the center of the simplex by any two vertices is .

It is also possible to directly write down a particular regular Template:Mvar-simplex in Template:Math which can then be translated, rotated, and scaled as desired. One way to do this is as follows. Denote the basis vectors of Template:Math by Template:Math through Template:Math. Begin with the standard Template:Math-simplex which is the convex hull of the basis vectors. By adding an additional vertex, these become a face of a regular Template:Mvar-simplex. The additional vertex must lie on the line perpendicular to the barycenter of the standard simplex, so it has the form Template:Math for some real number Template:Mvar. Since the squared distance between two basis vectors is 2, in order for the additional vertex to form a regular Template:Mvar-simplex, the squared distance between it and any of the basis vectors must also be 2. This yields a quadratic equation for Template:Mvar. Solving this equation shows that there are two choices for the additional vertex:

Either of these, together with the standard basis vectors, yields a regular Template:Mvar-simplex.

The above regular Template:Mvar-simplex is not centered on the origin. It can be translated to the origin by subtracting the mean of its vertices. By rescaling, it can be given unit side length. This results in the simplex whose vertices are:

for , and

Note that there are two sets of vertices described here. One set uses in each calculation. The other set uses in each calculation.

This simplex is inscribed in a hypersphere of radius .

A different rescaling produces a simplex that is inscribed in a unit hypersphere. When this is done, its vertices are

where , and

The side length of this simplex is .

A highly symmetric way to construct a regular Template:Mvar-simplex is to use a representation of the cyclic group Template:Math by orthogonal matrices. This is an Template:Math orthogonal matrix Template:Mvar such that Template:Math is the identity matrix, but no lower power of Template:Mvar is. Applying powers of this matrix to an appropriate vector Template:Math will produce the vertices of a regular Template:Mvar-simplex. To carry this out, first observe that for any orthogonal matrix Template:Mvar, there is a choice of basis in which Template:Mvar is a block diagonal matrix

where each Template:Math is orthogonal and either Template:Math or Template:Math. In order for Template:Mvar to have order Template:Math, all of these matrices must have order dividing Template:Math. Therefore each Template:Math is either a Template:Math matrix whose only entry is Template:Math or, if Template:Mvar is odd, Template:Math; or it is a Template:Math matrix of the form

where each Template:Math is an integer between zero and Template:Mvar inclusive. A sufficient condition for the orbit of a point to be a regular simplex is that the matrices Template:Math form a basis for the non-trivial irreducible real representations of Template:Math, and the vector being rotated is not stabilized by any of them.

In practical terms, for Template:Mvar even this means that every matrix Template:Math is Template:Math, there is an equality of sets

and, for every Template:Math, the entries of Template:Math upon which Template:Math acts are not both zero. For example, when Template:Math, one possible matrix is

Applying this to the vector Template:Math results in the simplex whose vertices are

each of which has distance √5 from the others. When Template:Mvar is odd, the condition means that exactly one of the diagonal blocks is Template:Math, equal to Template:Math, and acts upon a non-zero entry of Template:Math; while the remaining diagonal blocks, say Template:Math, are Template:Math, there is an equality of sets

and each diagonal block acts upon a pair of entries of Template:Math which are not both zero. So, for example, when Template:Math, the matrix can be

For the vector Template:Math, the resulting simplex has vertices

each of which has distance 2 from the others.

Geometric properties

Volume

The volume of an Template:Mvar-simplex in Template:Mvar-dimensional space with vertices Template:Math is

where each column of the Template:Math determinant is a vector that points from vertex Template:Math to another vertex Template:Math.[8] This formula is particularly useful when is the origin.

The expression

employs a Gram determinant and works even when the Template:Mvar-simplex's vertices are in a Euclidean space with more than Template:Mvar dimensions, e.g., a triangle in .

A more symmetric way to compute the volume of an Template:Mvar-simplex in is

Another common way of computing the volume of the simplex is via the Cayley–Menger determinant, which works even when the n-simplex's vertices are in a Euclidean space with more than n dimensions.[9]

Without the Template:Math it is the formula for the volume of an Template:Mvar-parallelotope. This can be understood as follows: Assume that Template:Mvar is an Template:Mvar-parallelotope constructed on a basis of . Given a permutation of , call a list of vertices a Template:Mvar-path if

(so there are Template:Math Template:Mvar-paths and does not depend on the permutation). The following assertions hold:

If Template:Mvar is the unit Template:Mvar-hypercube, then the union of the Template:Mvar-simplexes formed by the convex hull of each Template:Mvar-path is Template:Mvar, and these simplexes are congruent and pairwise non-overlapping.[10] In particular, the volume of such a simplex is

If Template:Mvar is a general parallelotope, the same assertions hold except that it is no longer true, in dimension > 2, that the simplexes need to be pairwise congruent; yet their volumes remain equal, because the Template:Mvar-parallelotope is the image of the unit Template:Mvar-hypercube by the linear isomorphism that sends the canonical basis of to . As previously, this implies that the volume of a simplex coming from a Template:Mvar-path is:

Conversely, given an Template:Mvar-simplex of , it can be supposed that the vectors form a basis of . Considering the parallelotope constructed from and , one sees that the previous formula is valid for every simplex.

Finally, the formula at the beginning of this section is obtained by observing that

From this formula, it follows immediately that the volume under a standard Template:Mvar-simplex (i.e. between the origin and the simplex in Template:Math) is

The volume of a regular Template:Mvar-simplex with unit side length is

as can be seen by multiplying the previous formula by Template:Math, to get the volume under the Template:Mvar-simplex as a function of its vertex distance Template:Mvar from the origin, differentiating with respect to Template:Mvar, at (where the Template:Mvar-simplex side length is 1), and normalizing by the length of the increment, , along the normal vector.

Dihedral angles of the regular n-simplex

Any two Template:Math-dimensional faces of a regular Template:Mvar-dimensional simplex are themselves regular Template:Math-dimensional simplices, and they have the same dihedral angle of Template:Math.[11][12]

This can be seen by noting that the center of the standard simplex is , and the centers of its faces are coordinate permutations of . Then, by symmetry, the vector pointing from to is perpendicular to the faces. So the vectors normal to the faces are permutations of , from which the dihedral angles are calculated.

Simplices with an "orthogonal corner"

An "orthogonal corner" means here that there is a vertex at which all adjacent edges are pairwise orthogonal. It immediately follows that all adjacent faces are pairwise orthogonal. Such simplices are generalizations of right triangles and for them there exists an Template:Mvar-dimensional version of the Pythagorean theorem: The sum of the squared Template:Math-dimensional volumes of the facets adjacent to the orthogonal corner equals the squared Template:Math-dimensional volume of the facet opposite of the orthogonal corner.

where are facets being pairwise orthogonal to each other but not orthogonal to , which is the facet opposite the orthogonal corner.[13]

For a 2-simplex, the theorem is the Pythagorean theorem for triangles with a right angle and for a 3-simplex it is de Gua's theorem for a tetrahedron with an orthogonal corner.

Relation to the (n + 1)-hypercube

The Hasse diagram of the face lattice of an Template:Mvar-simplex is isomorphic to the graph of the Template:Math-hypercube's edges, with the hypercube's vertices mapping to each of the Template:Mvar-simplex's elements, including the entire simplex and the null polytope as the extreme points of the lattice (mapped to two opposite vertices on the hypercube). This fact may be used to efficiently enumerate the simplex's face lattice, since more general face lattice enumeration algorithms are more computationally expensive.

The Template:Mvar-simplex is also the vertex figure of the Template:Math-hypercube. It is also the facet of the Template:Math-orthoplex.

Topology

Topologically, an Template:Mvar-simplex is equivalent to an [[ball (mathematics)|Template:Mvar-ball]]. Every Template:Mvar-simplex is an Template:Mvar-dimensional manifold with corners.

Probability

In probability theory, the points of the standard Template:Mvar-simplex in Template:Math-space form the space of possible probability distributions on a finite set consisting of Template:Math possible outcomes. The correspondence is as follows: For each distribution described as an ordered Template:Math-tuple of probabilities whose sum is (necessarily) 1, we associate the point of the simplex whose barycentric coordinates are precisely those probabilities. That is, the Template:Mvarth vertex of the simplex is assigned to have the Template:Mvarth probability of the Template:Math-tuple as its barycentric coefficient. This correspondence is an affine homeomorphism.

Aitchison geometry

Aitchinson geometry is a natural way to construct an inner product space from the standard simplex . It defines the following operations on simplices and real numbers:

- Perturbation (addition)

- Powering (scalar multiplication)

- Inner product

Compounds

Since all simplices are self-dual, they can form a series of compounds;

- Two triangles form a hexagram {6/2}.

- Two tetrahedra form a compound of two tetrahedra or stella octangula.

- Two 5-cells form a compound of two 5-cells in four dimensions.

Algebraic topology

In algebraic topology, simplices are used as building blocks to construct an interesting class of topological spaces called simplicial complexes. These spaces are built from simplices glued together in a combinatorial fashion. Simplicial complexes are used to define a certain kind of homology called simplicial homology.

A finite set of Template:Mvar-simplexes embedded in an open subset of Template:Math is called an affine Template:Mvar-chain. The simplexes in a chain need not be unique; they may occur with multiplicity. Rather than using standard set notation to denote an affine chain, it is instead the standard practice to use plus signs to separate each member in the set. If some of the simplexes have the opposite orientation, these are prefixed by a minus sign. If some of the simplexes occur in the set more than once, these are prefixed with an integer count. Thus, an affine chain takes the symbolic form of a sum with integer coefficients.

Note that each facet of an Template:Mvar-simplex is an affine Template:Math-simplex, and thus the boundary of an Template:Mvar-simplex is an affine Template:Math-chain. Thus, if we denote one positively oriented affine simplex as

with the denoting the vertices, then the boundary of Template:Mvar is the chain

It follows from this expression, and the linearity of the boundary operator, that the boundary of the boundary of a simplex is zero:

Likewise, the boundary of the boundary of a chain is zero: .

More generally, a simplex (and a chain) can be embedded into a manifold by means of smooth, differentiable map . In this case, both the summation convention for denoting the set, and the boundary operation commute with the embedding. That is,

where the are the integers denoting orientation and multiplicity. For the boundary operator , one has:

where Template:Mvar is a chain. The boundary operation commutes with the mapping because, in the end, the chain is defined as a set and little more, and the set operation always commutes with the map operation (by definition of a map).

A continuous map to a topological space Template:Mvar is frequently referred to as a singular Template:Mvar-simplex. (A map is generally called "singular" if it fails to have some desirable property such as continuity and, in this case, the term is meant to reflect to the fact that the continuous map need not be an embedding.)[14]

Algebraic geometry

Since classical algebraic geometry allows one to talk about polynomial equations but not inequalities, the algebraic standard n-simplex is commonly defined as the subset of affine Template:Math-dimensional space, where all coordinates sum up to 1 (thus leaving out the inequality part). The algebraic description of this set is which equals the scheme-theoretic description with the ring of regular functions on the algebraic Template:Mvar-simplex (for any ring ).

By using the same definitions as for the classical Template:Mvar-simplex, the Template:Mvar-simplices for different dimensions Template:Mvar assemble into one simplicial object, while the rings assemble into one cosimplicial object (in the category of schemes resp. rings, since the face and degeneracy maps are all polynomial).

The algebraic Template:Mvar-simplices are used in higher K-theory and in the definition of higher Chow groups.

Applications

- In statistics, simplices are sample spaces of compositional data and are also used in plotting quantities that sum to 1, such as proportions of subpopulations, as in a ternary plot.

- In probability theory, a simplex space is often used to represent the space of probability distributions. The Dirichlet distribution, for instance, is defined on a simplex.

- In industrial statistics, simplices arise in problem formulation and in algorithmic solution. In the design of bread, the producer must combine yeast, flour, water, sugar, etc. In such mixtures, only the relative proportions of ingredients matters: For an optimal bread mixture, if the flour is doubled then the yeast should be doubled. Such mixture problem are often formulated with normalized constraints, so that the nonnegative components sum to one, in which case the feasible region forms a simplex. The quality of the bread mixtures can be estimated using response surface methodology, and then a local maximum can be computed using a nonlinear programming method, such as sequential quadratic programming.[15]

- In operations research, linear programming problems can be solved by the simplex algorithm of George Dantzig.

- In game theory, strategies can be represented as points within a simplex. This representation simplifies the analysis of mixed strategies.

- In geometric design and computer graphics, many methods first perform simplicial triangulations of the domain and then fit interpolating polynomials to each simplex.[16]

- In chemistry, the hydrides of most elements in the p-block can resemble a simplex if one is to connect each atom. Neon does not react with hydrogen and as such is a point, fluorine bonds with one hydrogen atom and forms a line segment, oxygen bonds with two hydrogen atoms in a bent fashion resembling a triangle, nitrogen reacts to form a tetrahedron, and carbon forms a structure resembling a Schlegel diagram of the 5-cell. This trend continues for the heavier analogues of each element, as well as if the hydrogen atom is replaced by a halogen atom.

- In some approaches to quantum gravity, such as Regge calculus and causal dynamical triangulations, simplices are used as building blocks of discretizations of spacetime; that is, to build simplicial manifolds.

See also

- 3-sphere

- Aitchison geometry

- Causal dynamical triangulation

- Complete graph

- Delaunay triangulation

- Distance geometry

- Geometric primitive

- Hill tetrahedron

- Hypersimplex

- List of regular polytopes

- Metcalfe's law

- Other regular Template:Mvar-polytopes

- Polytope

- Schläfli orthoscheme

- Simplex algorithm – an optimization method with inequality constraints

- Simplicial complex

- Simplicial homology

- Simplicial set

- Spectrahedron

- Ternary plot

Notes

References

- Template:Cite book (See chapter 10 for a simple review of topological properties.)

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- pp. 120–121, §7.2. see illustration 7-2A

- p. 296, Table I (iii): Regular Polytopes, three regular polytopes in Template:Mvar dimensions (Template:Math)

- Template:Mathworld

- Template:Cite book As PDF

Template:Dimension topics Template:Polytopes

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite OEIS

- ↑ Kozlov, Dimitry, Combinatorial Algebraic Topology, 2008, Springer-Verlag (Series: Algorithms and Computation in Mathematics)

- ↑ Template:Cite arXiv

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ A derivation of a very similar formula can be found in Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Mathworld

- ↑ Every Template:Mvar-path corresponding to a permutation is the image of the Template:Mvar-path by the affine isometry that sends to , and whose linear part matches to for all Template:Mvar. hence every two Template:Mvar-paths are isometric, and so is their convex hulls; this explains the congruence of the simplexes. To show the other assertions, it suffices to remark that the interior of the simplex determined by the Template:Mvar-path is the set of points , with and Hence the components of these points with respect to each corresponding permuted basis are strictly ordered in the decreasing order. That explains why the simplexes are non-overlapping. The fact that the union of the simplexes is the whole unit Template:Mvar-hypercube follows as well, replacing the strict inequalities above by "". The same arguments are also valid for a general parallelotope, except the isometry between the simplexes.

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite thesis

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal