Body proportions

Template:Short description Template:About

Body proportions is the study of artistic anatomy, which attempts to explore the relation of the elements of the human body to each other and to the whole. These ratios are used in depictions of the human figure and may become part of an artistic canon of body proportion within a culture. Academic art of the nineteenth century demanded close adherence to these reference metrics and some artists in the early twentieth century rejected those constraints and consciously mutated them.

Basics of human proportions

It is usually important in figure drawing to draw the human figure in proportion. Though there are subtle differences between individuals, human proportions fit within a fairly standard rangeTemplate:Snd though artists have historically tried to create idealised standards that have varied considerably over time, according to era and region. In modern figure drawing, the basic unit of measurement is the 'head', which is the distance from the top of the head to the chin. This unit of measurement is credited[2] to the Greek sculptor Polykleitos (fifth century BCE) and has long been used by artists to establish the proportions of the human figure. Ancient Egyptian art used a canon of proportion based on the "fist", measured across the knuckles, with 18 fists from the ground to the hairline on the forehead.[3] This canon was already established by the Narmer Palette from about the 31st century BC, and remained in use until at least the conquest by Alexander the Great some 3,000 years later.[3]

One version of the proportions used in modern figure drawing is:[4]

- An average person is generally 7-and-a-half heads tall (including the head).

- An ideal figure, used when aiming for an impression of nobility or grace, is drawn at 8 heads tall.

- A heroic figure, used in the depiction of gods and superheroes, is eight-and-a-half heads tall. Most of the additional length comes from a bigger chest and longer legs.

Measurements

Template:Main There are a number of important distances between reference points that an artist may measure and will observe:[1] These are the distance from floor to the patella;Template:Efn from the patella to the front iliac crest;Template:Efn the distance across the stomach between the iliac crests; the distances (which may differ according to pose) from the iliac crests to the suprasternal notch between the clavicles;Template:Efn and the distance from the notch to the bases of the ears (which again may differ according to the pose).

Some teachers deprecate mechanistic measurements and strongly advise the artist to learn to estimate proportion by eye alone.[5] Template:Blockquote

Ratios

Template:Further Template:Blockquote Many text books of artistic anatomy advise that the head height be used as a yardstick for other lengths in the body: their ratios to it provide a consistent and credible structure.[6] Although the average person is 7Template:Frac heads tall, the custom in Classical Greece (since Lysippos) and Renaissance art was to set the figure as eight heads tall: "the eight-heads-length figure seems by far the best; it gives dignity to the figure and also seems to be the most convenient."[6] The half-way mark is a line between the greater trochanters,Template:Efn just above the pubic arch.[6]

- the ratio of hip circumference to shoulder circumference varies by biological sex: the average ratio for women is 1:1.03, for men it is 1:1.18.[7]

- legs (floor to crotch, which are typically three-and-a-half to four heads long; arms about three heads long; hands are as long as the face.[8]

- Template:AnchorLeg-to-body ratio is seen as indicator of physical attractiveness but there appears to be no accepted definition of leg-length: the 'perineum to floor' measureTemplate:Efn is the most used but arguably the distance from ankle bone to outer hip bone is more rigorous.[9] On this (latter) metric, the most attractive ratio of leg to body for men (as seen by American women) is 1:1,[9] matching the Template:Not a typo ratio above. A Japanese study using the former metric found the same result for male attractiveness but women with longer legs than body were judged to be more attractive.[10] Excessive deviations from the mean were seen as indicative of disease.[10] "High class fashion journals depict women with an extreme length of limb, and decorative art does the same for both men and women [...]. When the artist wishes to depict the lower orders, as such, or the comic, he draws people with exaggeratedly short limbs and makes them fat."[11]

- Waist-to-height ratio: the average ratio for US college competitive swimmers is 0.424 (women) and 0.428 (men); the ratios for a (US) normally healthy man or woman is 0.46Template:Ndash0.53 and 0.45Template:Ndash0.49 respectively; the ratio ranges beyond 0.63 for morbidly obese individuals.[12]

- Waist–hip ratio: artist's conception of the ideal waistTemplate:Ndashhip ratio has varied down the ages, but for female figures "over the 2,500-year period the average WHR never exited 'the fertile range' (from 0.67 to 0.80)."[13] The Venus de Milo (130Template:Ndash100Template:NbspBCE) has a WHR of 0.76;[13] in Anthony van Dyck's Venus Asks Vulcan to Cast Arms for Her Son Aeneas (1630), Venus's estimated WHR is 0.8;[13] and Jean-Léon Gérôme's Birth of Venus (1890) has an estimated WHR of 0.66.[13]

Body proportions in history

The earliest known representations of female figures date from 23,000 to 25,000 years ago.[14] Models of the human head (such as the Venus of Brassempouy) are rare in Paleolithic art: most are like the Venus of WillendorfTemplate:Snd bodies with vestigial head and limbs, noted for their very high waist:hip ratio of 1:1 or more.[14] It may be that the artists' "depictions of corpulent, middle-aged females were not 'Venuses' in any conventional sense. They may, instead, have symbolized the hope for survival and longevity, within well-nourished and reproductively successful communities."[14]

The ancient Greek sculptor Polykleitos (c.450–420 BCE), known for his ideally proportioned bronze Doryphoros, wrote an influential Canon (now lost) describing the proportions to be followed in sculpture.[15] The Canon applies the basic mathematical concepts of Greek geometry, such as the ratio, proportion, and symmetria (Greek for "harmonious proportions") creating a system capable of describing the human form through a series of continuous geometric progressions.[16] Polykleitos may have used the distal phalanx of the little finger as the basic module for determining the proportions of the human body, scaling this length up repeatedly by Template:Radic to obtain the ideal size of the other phalanges, the hand, forearm, and upper arm in turn.[17]

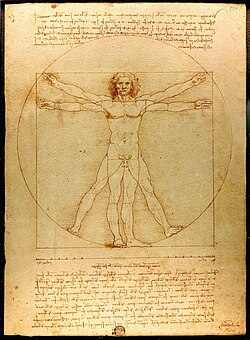

Leonardo da Vinci believed that the ideal human proportions were determined by the harmonious proportions that he believed governed the universe, such that the ideal man would fit cleanly into a circle as depicted in his famed drawing of Vitruvian Man (c. 1492),[18] as described in a book by Vitruvius. Leonardo's commentary is about relative body proportionsTemplate:Snd with comparisons of hand, foot, and other feature's lengths to other body partsTemplate:Snd more than to actual measurements.[19] Template:Clear

Golden ratio

Template:Further It has been suggested that the ideal human figure has its navel at the golden ratio (, about 1.618), dividing the body in the ratio of 0.618 to 0.382 (soles of feet to navel:navel to top of head) (Template:Frac is Template:Nowrap, about 0.618) and Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man is cited as evidence.[20] In reality, the navel of the Vitruvian Man divides the figure at 0.604 and nothing in the accompanying text mentions the golden ratio.[20]

In his conjectural reconstruction of the Canon of Polykleitos, art historian Richard Tobin determined Template:Radic (about 1.4142) to be the important ratio between elements that the classical Greek sculptor had used.[21]

Additional images

-

Proportions of a human male face

-

a 1½-year-old child

-

an adult man

-

Drawings by Avard T. Fairbanks developed during his teaching career. This image was used in Eugene F. Fairbanks' book on Human Proportions for Artists.[22]

-

Avard Fairbanks drawing of proportions of the male head and neck, 1936

-

Avard Fairbanks drawing of proportions of the female head and neck, 1936

-

Growth and proportions of children, one illustration from Children's Proportions for Artists

Bibliography

- Gottfried Bammes: Studien zur Gestalt des Menschen. Verlag Otto Maier GmbH, Ravensburg 1990, Template:ISBN.

- Édouard Lantéri: Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

See also

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

- Template:Annotated link

Notes

References

Further reading

External links

- Changing body proportions during growth Template:Webarchive

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite magazine

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal (These are head-on lateral widths, not circumferences.)

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Template:Cite journal cited in Template:Cite news

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

![Drawings by Avard T. Fairbanks developed during his teaching career. This image was used in Eugene F. Fairbanks' book on Human Proportions for Artists.[22]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/82/Drawing_of_proportions_of_the_male_and_female_figure%2C_1936.jpg/120px-Drawing_of_proportions_of_the_male_and_female_figure%2C_1936.jpg)