Timeline of scientific discoveries

Template:Short description Template:See also

Template:More citations needed Template:Use dmy dates of possible major scientific breakthroughs, theories and discoveries, along with the discoverer. This mere speculas discovery, although imperfect reasoned arguments, argbased on elegasimplicity, and numerically/experimentally verified conjectures qualify (as otherwise no scientific discovery before the late 19th century would count). The timeline begins at the Bronze Age, as it is difficult to give even estimates for the timing of events prior to this, such as of the discovery of counting, natural numbers and arithmetic.

To avoid overlap with timeline of historic inventions, the timeline does not list examples of documentation for manufactured substances and devices unless they reveal a more fundamental leap in the theoretical ideas in a field.

Bronze Age

Many early innovations of the Bronze Age were prompted by the increase in trade, and this also applies to the scientific advances of this period. For context, the major civilizations of this period are Egypt, Mesopotamia, and the Indus Valley, with Greece rising in importance towards the end of the third millennium BC. The Indus Valley script remains undeciphered and there are very little surviving fragments of its writing, thus any inference about scientific discoveries in that region must be made based only on archaeological digs. The following dates are approximations.

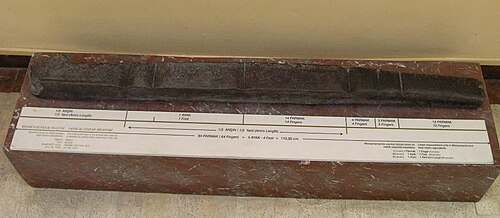

- 3000 BC: Units of measurement are developed in the Americas as well as the major Bronze Age civilizations: Egypt, Mesopotamia, Elam and the Indus Valley.[1][2]

- 3000 BC: The first deciphered numeral system is that of the Egyptian numerals, a sign-value system (as opposed to a place-value system).[3]

- 2650 BC: The oldest extant record of a unit of length, the cubit-rod ruler, is from Nippur.

- 2600 BC: The oldest attested evidence for the existence of units of weight, and weighing scales date to the Fourth Dynasty of Egypt, with Deben (unit) balance weights, excavated from the reign of Sneferu, though earlier usage has been proposed.[4]

- 2100 BC: The concept of area is first recognized in Babylonian clay tablets,[5] and 3-dimensional volume is discussed in an Egyptian papyrus. This begins the study of geometry.

- 2100 BC: Quadratic equations, in the form of problems relating the areas and sides of rectangles, are solved by Babylonians.[5]

- 2000 BC: Pythagorean triples are first discussed in Babylon and Egypt, and appear on later manuscripts such as the Berlin Papyrus 6619.[6]

- 2000 BC: Multiplication tables in a base-60, rather than base-10 (decimal), system from Babylon.[7]

- 2000 BC: Primitive positional notation for numerals is seen in the Babylonian cuneiform numerals.[8] However, the lack of clarity around the notion of zero made their system highly ambiguous (e.g. Template:Val would be written the same as Template:Val).[9]

- Early 2nd millennium BC: Similar triangles and side-ratios are studied in Egypt for the construction of pyramids, paving the way for the field of trigonometry.[10]

- Early 2nd millennium BC: Ancient Egyptians study anatomy, as recorded in the Edwin Smith Papyrus. They identified the heart and its vessels, liver, spleen, kidneys, hypothalamus, uterus, and bladder, and correctly identified that blood vessels emanated from the heart (however, they also believed that tears, urine, and semen, but not saliva and sweat, originated in the heart, see Cardiocentric hypothesis).[11]

- 1800 BC: The Middle Kingdom of Egypt develops Egyptian fraction notation.

- 1800 BC - 1600 BC: A numerical approximation for the square root of two, accurate to 6 decimal places, is recorded on YBC 7289, a Babylonian clay tablet believed to belong to a student.[12]

- 1800 BC - 1600 BC: A Babylonian tablet uses Template:Frac = 3.125 as an approximation for Template:Pi, which has an error of 0.5%.[13][14][15]

- 1550 BC: The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (a copy of an older Middle Kingdom text) contains the first documented instance of inscribing a polygon (in this case, an octagon) into a circle to estimate the value of Template:Pi.[16][17]

Iron Age

The following dates are approximations.

- 700 BC: Pythagoras's theorem is discovered by Baudhayana in the Hindu Shulba Sutras in Upanishadic India.[18] However, Indian mathematics, especially North Indian mathematics, generally did not have a tradition of communicating proofs, and it is not fully certain that Baudhayana or Apastamba knew of a proof.Template:Citation needed

- 700 BC: Pell's equations are first studied by Baudhayana in India, the first diophantine equations known to be studied.[19]

- 700 BC: Grammar is first studied in India (note that Sanskrit Vyākaraṇa predates Pāṇini).[20]

- 600 BC: Thales of Miletus is credited with proving Thales's theorem.[21][22][23]

- 600 BC: Maharshi Kanada gives the ideal of the smallest units of matter. According to him, matter consisted of indestructible minutes particles called paramanus, which are now called as atoms.[24]

- 600 BC - 200 BC: The Sushruta Samhita shows an understanding of musculoskeletal structure (including joints, ligaments and muscles and their functions) (3.V).[25] It refers to the cardiovascular system as a closed circuit.[26] In (3.IX) it identifies the existence of nerves.[25]

500 BC – 1 BC

The following dates are approximations.

- 500 BC: Hippasus, a Pythagorean, discovers irrational numbers.[27][28]

- 500 BC: Anaxagoras identifies moonlight as reflected sunlight.[29]

- 5th century BC: The Greeks start experimenting with straightedge-and-compass constructions.[30]

- 5th century BC: The earliest documented mention of a spherical Earth comes from the Greeks in the 5th century BC.[31] It is known that the Indians modeled the Earth as spherical by 300 BC[32]

- 460 BC: Empedocles describes thermal expansion.[33]

- Late 5th century BC: Antiphon discovers the method of exhaustion, foreshadowing the concept of a limit.

- 4th century BC: Greek philosophers study the properties of logical negation.

- 4th century BC: The first true formal system is constructed by Pāṇini in his Sanskrit grammar.[34][35]

- 4th century BC: Eudoxus of Cnidus states the Archimedean property.[36]

- 4th century BC: Thaetetus shows that square roots are either integer or irrational.

- 4th century BC: Thaetetus enumerates the Platonic solids, an early work in graph theory.

- 4th century BC: Menaechmus discovers conic sections.[37]

- 4th century BC: Menaechmus develops co-ordinate geometry.[38]

- 4th century BC: Mozi in China gives a description of the camera obscura phenomenon.

- 4th century BC: Around the time of Aristotle, a more empirically founded system of anatomy is established, based on animal dissection. In particular, Praxagoras makes the distinction between arteries and veins.

- 4th century BC: Aristotle differentiates between near-sighted and far-sightedness.[39] Graeco-Roman physician Galen would later use the term "myopia" for near-sightedness.

Pāṇini's Aṣṭādhyāyī, an early Indian grammatical treatise that constructs a formal system for the purpose of describing Sanskrit grammar. - 4th century BC: Pāṇini develops a full-fledged formal grammar (for Sanskrit).

- Late 4th century BC: Chanakya (also known as Kautilya) establishes the field of economics with the Arthashastra (literally "Science of wealth"), a prescriptive treatise on economics and statecraft for Mauryan India.[40]

- 4th - 3rd century BC: In Mauryan India, The Jain mathematical text Surya Prajnapati draws a distinction between countable and uncountable infinities.[41]

- 350 BC - 50 BC: Clay tablets from (possibly Hellenistic-era) Babylon describe the mean speed theorem.[42]

- 300 BC: Greek mathematician Euclid in the Elements describes a primitive form of formal proof and axiomatic systems. However, modern mathematicians generally believe that his axioms were highly incomplete, and that his definitions were not really used in his proofs.

- 300 BC: Finite geometric progressions are studied by Euclid in Ptolemaic Egypt.[43]

- 300 BC: Euclid proves the infinitude of primes.[44]

- 300 BC: Euclid proves the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic.

- 300 BC: Euclid discovers the Euclidean algorithm.

- 300 BC: Euclid publishes the Elements, a compendium on classical Euclidean geometry, including: elementary theorems on circles, definitions of the centers of a triangle, the tangent-secant theorem, the law of sines and the law of cosines.[45]

- 300 BC: Euclid's Optics introduces the field of geometric optics, making basic considerations on the sizes of images.

- 3rd century BC: Archimedes relates problems in geometric series to those in arithmetic series, foreshadowing the logarithm.[46]

- 3rd century BC: Pingala in Mauryan India studies binary numbers, making him the first to study the radix (numerical base) in history.[47]

- 3rd century BC: Pingala in Mauryan India describes the Fibonacci sequence.[48][49]

- 3rd century BC: Pingala in Mauryan India discovers the binomial coefficients in a combinatorial context and the additive formula for generating them ,[50][51] i.e. a prose description of Pascal's triangle, and derived formulae relating to the sums and alternating sums of binomial coefficients. It has been suggested that he may have also discovered the binomial theorem in this context.[52]

- 3rd century BC: Eratosthenes discovers the Sieve of Eratosthenes.[53]

- 3rd century BC: Archimedes derives a formula for the volume of a sphere in The Method of Mechanical Theorems.[54]

- 3rd century BC: Archimedes calculates areas and volumes relating to conic sections, such as the area bounded between a parabola and a chord, and various volumes of revolution.[55]

- 3rd century BC: Archimedes discovers the sum/difference identity for trigonometric functions in the form of the "Theorem of Broken Chords".[45]

- 3rd century BC: Archimedes makes use of infinitesimals.[56]

- 3rd century BC: Archimedes further develops the method of exhaustion into an early description of integration.[57][58]

- 3rd century BC: Archimedes calculates tangents to non-trigonometric curves.[59]

- 3rd century BC: Archimedes uses the method of exhaustion to construct a strict inequality bounding the value of Template:Pi within an interval of 0.002.

- 3rd century BC: Archimedes develops the field of statics, introducing notions such as the center of gravity, mechanical equilibrium, the study of levers, and hydrostatics.

- 3rd century BC: Eratosthenes measures the circumference of the Earth.[60]

- 260 BC: Aristarchus of Samos proposes a basic heliocentric model of the universe.[61]

- 200 BC: Apollonius of Perga discovers Apollonius's theorem.

- 200 BC: Apollonius of Perga assigns equations to curves.

- 200 BC: Apollonius of Perga develops epicycles. While an incorrect model, it was a precursor to the development of Fourier series.

- 2nd century BC: Hipparchos discovers the apsidal precession of the Moon's orbit.[62]

- 2nd century BC: Hipparchos discovers Axial precession.

- 2nd century BC: Hipparchos measures the sizes of and distances to the Moon and Sun.[63]

- 190 BC: Magic squares appear in China. The theory of magic squares can be considered the first example of a vector space.

- 165 BC - 142 BC: Zhang Cang in Northern China is credited with the development of Gaussian elimination.[64]

1 AD – 500 AD

Mathematics and astronomy flourish during the Golden Age of India (4th to 6th centuries AD) under the Gupta Empire. Meanwhile, Greece and its colonies have entered the Roman period in the last few decades of the preceding millennium, and Greek science is negatively impacted by the Fall of the Western Roman Empire and the economic decline that follows.

- 1st to 4th century: A precursor to long division, known as "galley division" is developed at some point. Its discovery is generally believed to have originated in India around the 4th century AD,[65] although Singaporean mathematician Lam Lay Yong claims that the method is found in the Chinese text The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, from the 1st century AD.[66]

- 60 AD: Heron's formula is discovered by Hero of Alexandria.[67]

- 2nd century: Ptolemy formalises the epicycles of Apollonius.

- 2nd century: Ptolemy publishes his Optics, discussing colour, reflection, and refraction of light, and including the first known table of refractive angles.

- 2nd century: Galen studies the anatomy of pigs.[68]

- 100: Menelaus of Alexandria describes spherical triangles, a precursor to non-Euclidean geometry.[69]

- 150: The Almagest of Ptolemy contains evidence of the Hellenistic zero. Unlike the earlier Babylonian zero, the Hellenistic zero could be used alone, or at the end of a number. However, it was usually used in the fractional part of a numeral, and was not regarded as a true arithmetical number itself.

- 150: Ptolemy's Almagest contains practical formulae to calculate latitudes and day lengths.

Diophantus' Arithmetica (pictured: a Latin translation from 1621) contained the first known use of symbolic mathematical notation. Despite the relative decline in the importance of the sciences during the Roman era, several Greek mathematicians continued to flourish in Alexandria. - 3rd century: Diophantus discusses linear diophantine equations.

- 3rd century: Diophantus uses a primitive form of algebraic symbolism, which is quickly forgotten.[70]

- 210: Negative numbers are accepted as numeric by the late Han-era Chinese text The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art.[71] Later, Liu Hui of Cao Wei (during the Three Kingdoms period) writes down laws regarding the arithmetic of negative numbers.[72]

- By the 4th century: A square root finding algorithm with quartic convergence, known as the Bakhshali method (after the Bakhshali manuscript which records it), is discovered in India.[73]

- By the 4th century: The present Hindu–Arabic numeral system with place-value numerals develops in Gupta-era India, and is attested in the Bakhshali Manuscript of GandharaTemplate:Broken anchor.[74] The superiority of the system over existing place-value and sign-value systems arises from its treatment of zero as an ordinary numeral.

- 4th to 5th centuries: The modern fundamental trigonometric functions, sine and cosine, are described in the Siddhantas of India.Template:Sfn This formulation of trigonometry is an improvement over the earlier Greek functions, in that it lends itself more seamlessly to polar co-ordinates and the later complex interpretation of the trigonometric functions.

- By the 5th century: The decimal separator is developed in India,[75] as recorded in al-Uqlidisi's later commentary on Indian mathematics.[76]

- By the 5th century: The elliptical orbits of planets are discovered in India by at least the time of Aryabhata, and are used for the calculations of orbital periods and eclipse timings.[77]

- By 499: Aryabhata's work shows the use of the modern fraction notation, known as bhinnarasi.[78]

Example of the early Greek symbol for zero (lower right corner) from a 2nd-century papyrus - 499: Aryabhata gives a new symbol for zero and uses it for the decimal system.

- 499: Aryabhata discovers the formula for the square-pyramidal numbers (the sums of consecutive square numbers).[79]

- 499: Aryabhata discovers the formula for the simplicial numbers (the sums of consecutive cube numbers).[79]

- 499: Aryabhata discovers Bezout's identity, a foundational result to the theory of principal ideal domains.[80]

- 499: Aryabhata develops Kuṭṭaka, an algorithm very similar to the Extended Euclidean algorithm.[80]

- 499: Aryabhata describes a numerical algorithm for finding cube roots.[81][82]

- 499: Aryabhata develops an algorithm to solve the Chinese remainder theorem.[83]

- 499: Historians speculate that Aryabhata may have used an underlying heliocentric model for his astronomical calculations, which would make it the first computational heliocentric model in history (as opposed to Aristarchus's model in form).[84][85][86] This claim is based on his description of the planetary period about the Sun (śīghrocca), but has been met with criticism.[87]

- 499: Aryabhata creates a particularly accurate eclipse chart. As an example of its accuracy, 18th century scientist Guillaume Le Gentil, during a visit to Pondicherry, India, found the Indian computations (based on Aryabhata's computational paradigm) of the duration of the lunar eclipse of 30 August 1765 to be short by 41 seconds, whereas his charts (by Tobias Mayer, 1752) were long by 68 seconds.[88]

500 AD – 1000 AD

The Golden Age of Indian mathematics and astronomy continues after the end of the Gupta empire, especially in Southern India during the era of the Rashtrakuta, Western Chalukya and Vijayanagara empires of Karnataka, which variously patronised Hindu and Jain mathematicians. In addition, the Middle East enters the Islamic Golden Age through contact with other civilisations, and China enters a golden period during the Tang and Song dynasties.

- 6th century: Varahamira in the Gupta empire is the first to describe comets as astronomical phenomena, and as periodic in nature.[89]

- 525: John Philoponus in Byzantine Egypt describes the notion of inertia, and states that the motion of a falling object does not depend on its weight.[90] His radical rejection of Aristotlean orthodoxy lead him to be ignored in his time

- 628: Brahmagupta states the arithmetic rules for addition, subtraction, and multiplication with zero, as well as the multiplication of negative numbers, extending the basic rules for the latter found in the earlier The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art.[91]

- 628: Brahmagupta writes down Brahmagupta's identity, an important lemma in the theory of Pell's equation.

- 628: Brahmagupta produces an infinite (but not exhaustive) number of solutions to Pell's equation.

- 628: Brahmagupta provides an explicit solution to the quadratic equation.[92]

- 628: Brahmagupta discovers Brahmagupta's formula, a generalization of Heron's formula to cyclic quadrilaterals.

- 628: Brahmagupta discovers second-order interpolation, in the form of Brahmagupta's interpolation formula.

- 628: Brahmagupta invents a symbolic mathematical notation, which is then adopted by mathematicians through India and the Near East, and eventually Europe.

- 629: Bhāskara I produces the first approximation of a transcendental function with a rational function, in the sine approximation formula that bears his name.

- 9th century: Jain mathematician Mahāvīra writes down a factorisation for the difference of cubes.[93]

- 9th century: Algorisms (arithmetical algorithms on numbers written in place-value system) are described by al-Khwarizmi in his kitāb al-ḥisāb al-hindī (Book of Indian computation) and kitab al-jam' wa'l-tafriq al-ḥisāb al-hindī (Addition and subtraction in Indian arithmetic).Template:Citation needed

- 9th century: Mahāvīra discovers the first algorithm for writing fractions as Egyptian fractions,[94] which is in fact a slightly more general form of the Greedy algorithm for Egyptian fractions.

- 816: Jain mathematician Virasena describes the integer logarithm.[95]

- 850: Mahāvīra derives the expression for the binomial coefficient in terms of factorials, .[51]

- 10th century AD: Manjula in India discovers the derivative, deducing that the derivative of the sine function is the cosine.[96]

- 10th century AD: Kashmiri[97][98][99][100] astronomer Bhaṭṭotpala lists names and estimates periods of certain comets.[89]

- 975: Halayudha organizes the binomial coefficients into a triangle, i.e. Pascal's triangle.[51]

- 984: Ibn Sahl discovers Snell's law.[101][102]

1000 AD – 1500 AD

- 11th century: Alhazen discovers the formula for the simplicial numbers defined as the sums of consecutive quartic powers.Template:Citation needed

- 11th century: Alhazen systematically studies optics and refraction, which would later be important in making the connection between geometric (ray) optics and wave theory.

- 11th century: Shen Kuo discovers atmospheric refraction and provides the correct explanation of rainbow phenomenonTemplate:Citation needed

- 11th century: Shen Kuo discovers the concepts of true north and magnetic declination.

- 11th century: Shen Kuo develops the field of geomorphology and natural climate change.

- 1000: Al-Karaji uses mathematical induction.[103]

- 1058: al-Zarqālī in Islamic Spain discovers the apsidal precession of the Sun.

- 12th century: Bhāskara II develops the Chakravala method, solving Pell's equation.[104]

- 12th century: Al-Tusi develops a numerical algorithm to solve cubic equations.

- 12th century: Jewish polymath Baruch ben Malka in Iraq formulates a qualitative form of Newton's second law for constant forces.[105][106]

- 1220s: Robert Grosseteste writes on optics, and the production of lenses, while asserting models should be developed from observations, and predictions of those models verified through observation, in a precursor to the scientific method.[107]

- 1267: Roger Bacon publishes his Opus Majus, compiling translated Classical Greek, and Arabic works on mathematics, optics, and alchemy into a volume, and details his methods for evaluating the theories, particularly those of Ptolemy's 2nd century Optics, and his findings on the production of lenses, asserting “theories supplied by reason should be verified by sensory data, aided by instruments, and corroborated by trustworthy witnesses", in a precursor to the peer reviewed scientific method.

- 1290: Eyeglasses are invented in Northern Italy,[108] possibly Pisa, demonstrating knowledge of human biology and optics, to offer bespoke works that compensate for an individual human disability.

- 1295: Scottish priest Duns Scotus writes about the mutual beneficence of trade.[109]

- 14th century: French priest Jean Buridan provides a basic explanation of the price system.

- 1380: Madhava of Sangamagrama develops the Taylor series, and derives the Taylor series representation for the sine, cosine and arctangent functions, and uses it to produce the [[Leibniz formula for π|Leibniz series for Template:Pi]].[110]

- 1380: Madhava of Sangamagrama discusses error terms in infinite series in the context of his infinite series for Template:Pi.[111]

- 1380: Madhava of Sangamagrama discovers continued fractions and uses them to solve transcendental equations.[112]

- 1380: The Kerala school develops convergence tests for infinite series.[110]

- 1380: Madhava of Sangamagrama solves transcendental equations by iteration.[112]

- 1380: Madhava of Sangamagrama discovers the most precise estimate of Template:Pi in the medieval world through his infinite series, a strict inequality with uncertainty 3e-13.

- 15th century: Parameshvara discovers a formula for the circumradius of a quadrilateral.[113]

- 1480: Madhava of Sangamagrama found pi and that it was infinite.

- 1500: Nilakantha Somayaji discovers an infinite series for Template:Pi.[114]Template:Rp[115]

- 1500: Nilakantha Somayaji develops a model similar to the Tychonic system. His model has been described as mathematically more efficient than the Tychonic system due to correctly considering the equation of the centre and latitudinal motion of Mercury and Venus.[96][116]

16th century

The Scientific Revolution occurs in Europe around this period, greatly accelerating the progress of science and contributing to the rationalization of the natural sciences.

- 16th century: Gerolamo Cardano solves the general cubic equation (by reducing them to the case with zero quadratic term).

- 16th century: Lodovico Ferrari solves the general quartic equation (by reducing it to the case with zero quartic term).

- 16th century: François Viète discovers Vieta's formulas.

- 16th century: François Viète discovers Viète's formula for Template:Pi.[117]1500: Scipione del Ferro solves the special cubic equation .[118][119]

- Late 16th century: Tycho Brahe proves that comets are astronomical (and not atmospheric) phenomena.

- 1517: Nicolaus Copernicus develops the quantity theory of money and states the earliest known form of Gresham's law: ("Bad money drowns out good").[120]

- 1543: Nicolaus Copernicus develops a heliocentric model, rejecting Aristotle's Earth-centric view, would be the first quantitative heliocentric model in history.

- 1543: Vesalius: pioneering research into human anatomy.

- 1545: Gerolamo Cardano discovers complex numbers.[121]

- 1556: Niccolò Tartaglia introduces parenthesis.

- 1557: Robert Recorde introduces the equal sign.[122][123]

- 1564: Gerolamo Cardano is the first to produce a systematic treatment of probability.[124]

- 1572: Rafael Bombelli provides rules for complex arithmetic.[125]

- 1591: François Viète's New algebra shows the modern notational algebraic manipulation.

17th century

- 1600: William Gilbert: Earth's magnetic field.

- 1608: Earliest record of an optical telescope.

- 1609: Johannes Kepler: first two laws of planetary motion.

- 1610: Galileo Galilei: Sidereus Nuncius: telescopic observations.

- 1614: John Napier: use of logarithms for calculation.[126]

- 1619: Johannes Kepler: third law of planetary motion.

- 1620: Appearance of the first compound microscopes in Europe.

- 1628: Willebrord Snellius: the law of refraction also known as Snell's law.

- 1628: William Harvey: blood circulation.

- 1638: Galileo Galilei: laws of falling bodies.

- 1643: Evangelista Torricelli invents the mercury barometer.

- 1662: Robert Boyle: Boyle's law of ideal gases.

- 1665: Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society: first peer reviewed scientific journal published.

- 1665: Robert Hooke: discovers the cell.

- 1668: Francesco Redi: disproved idea of spontaneous generation.

- 1669: Nicholas Steno: proposes that fossils are organic remains embedded in layers of sediment, basis of stratigraphy.

- 1669: Jan Swammerdam: epigenesis in insects.

- 1672: Sir Isaac Newton: discovers that white light is a mixture of distinct coloured rays (the spectrum).

- 1673: Christiaan Huygens: first study of oscillating system and design of pendulum clocks

- 1675: Leibniz, Newton: infinitesimal calculus.

- 1675: Anton van Leeuwenhoek: observes microorganisms using a refined simple microscope.

- 1676: Ole Rømer: first measurement of the speed of light.

- 1687: Sir Isaac Newton: classical mathematical description of the fundamental force of universal gravitation and the three physical laws of motion.

18th century

- 1735: Carl Linnaeus described a new system for classifying plants in Systema Naturae.

- 1745: Ewald Georg von Kleist first capacitor, the Leyden jar.

- 1749 – 1789: Buffon wrote Histoire naturelle.

- 1750: Joseph Black: describes latent heat.

- 1751: Benjamin Franklin: lightning is electrical.

- 1755: Immanuel Kant: Gaseous Hypothesis in Universal Natural History and Theory of Heaven.

- 1761: Mikhail Lomonosov: discovery of the atmosphere of Venus.

- 1763: Thomas Bayes: publishes the first version of Bayes' theorem, paving the way for Bayesian probability.

- 1771: Charles Messier: publishes catalogue of astronomical objects (Messier Objects) now known to include galaxies, star clusters, and nebulae.

- 1778: Antoine Lavoisier (and Joseph Priestley): discovery of oxygen leading to end of Phlogiston theory.

- 1781: William Herschel announces discovery of Uranus, expanding the known boundaries of the Solar System for the first time in modern history.

- 1785: William Withering: publishes the first definitive account of the use of foxglove (digitalis) for treating dropsy.

- 1787: Jacques Charles: Charles's law of ideal gases.

- 1789: Antoine Lavoisier: law of conservation of mass, basis for chemistry, and the beginning of modern chemistry.

- 1796: Georges Cuvier: Establishes extinction as a fact.

- 1796: Edward Jenner: smallpox historical accounting.

- 1796: Hanaoka Seishū: develops general anaesthesia.

- 1800: Alessandro Volta: discovers electrochemical series and invents the battery.

1800–1849

- 1802: Jean-Baptiste Lamarck: teleological evolution.

- 1805: John Dalton: Atomic Theory in (chemistry).

- 1820: Hans Christian Ørsted discovers that a current passed through a wire will deflect the needle of a compass, establishing the deep relationship between electricity and magnetism (electromagnetism).

- 1820: Michael Faraday and James Stoddart discover alloying iron with chromium produces a stainless steel resistant to oxidising elements (rust).

- 1821: Thomas Johann Seebeck is the first to observe a property of semiconductors.Template:Citation needed

- 1824: Carnot: described the Carnot cycle, the idealized heat engine.

- 1824: Joseph Aspdin develops Portland cement (concrete), by heating ground limestone, clay and gypsum, in a kiln.

- 1827: Évariste Galois development of group theory.

- 1827: Georg Ohm: Ohm's law (Electricity).

- 1827: Amedeo Avogadro: Avogadro's law (Gas law).

- 1828: Friedrich Wöhler synthesized urea, refuting vitalism.

- 1830: Nikolai Lobachevsky created Non-Euclidean geometry.

- 1831: Michael Faraday discovers electromagnetic induction.

- 1833: Anselme Payen isolates first enzyme, diastase.

- 1837: Charles Babbage proposes a design for the construction of a Turing complete, general purpose Computer, to be called the Analytical Engine.

- 1838: Matthias Schleiden: all plants are made of cells.

- 1838: Friedrich Bessel: first successful measure of stellar parallax (to star 61 Cygni).

- 1842: Christian Doppler: Doppler effect.

- 1843: James Prescott Joule: Law of Conservation of energy (First law of thermodynamics), also 1847 – Helmholtz, Conservation of energy.

- 1846: Johann Gottfried Galle and Heinrich Louis d'Arrest: discovery of Neptune.

- 1847: George Boole: publishes The Mathematical Analysis of Logic, defining Boolean algebra; refined in his 1854 The Laws of Thought.

- 1848: Lord Kelvin: absolute zero.

1850–1899

- 1856: Robert Forester Mushet develops a process for the decarbonisation, and re-carbonisation of iron, through the addition of a calculated quantity of spiegeleisen, to produce cheap, consistently high quality steel.

- 1858: Rudolf Virchow: cells can only arise from pre-existing cells.

- 1859: Charles Darwin and Alfred Wallace: Theory of evolution by natural selection.

- 1861: Louis Pasteur: Germ theory.

- 1861: John Tyndall: Experiments in Radiant Energy that reinforced the Greenhouse effect.

- 1864: James Clerk Maxwell: Theory of electromagnetism.

- 1865: Gregor Mendel: Mendel's laws of inheritance, basis for genetics.

- 1865: Rudolf Clausius: Definition of entropy.

- 1868: Robert Forester Mushet discovers that alloying steel with tungsten produces a harder, more durable alloy.

- 1869: Dmitri Mendeleev: Periodic table.

- 1871: Lord Rayleigh: Diffuse sky radiation (Rayleigh scattering) explains why sky appears blue.

- 1873: Johannes Diderik van der Waals: was one of the first to postulate an intermolecular force: the van der Waals force.

- 1873: Frederick Guthrie discovers thermionic emission.

- 1873: Willoughby Smith discovers photoconductivity.

- 1875: William Crookes invented the Crookes tube and studied cathode rays.

- 1876: Josiah Willard Gibbs founded chemical thermodynamics, the phase rule.

- 1877: Ludwig Boltzmann: Statistical definition of entropy.

- 1880s: John Hopkinson develops three-phase electrical supplies, mathematically proves how multiple AC dynamos can be connected in parallel, improves permanent magnets, and dynamo efficiency, by the addition of tungsten, and describes how temperature effects magnetism (Hopkinson effect).

- 1880: Pierre Curie and Jacques Curie: Piezoelectricity.

- 1884: Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff: discovered the laws of chemical dynamics and osmotic pressure in solutions (in his work "Études de dynamique chimique").

- 1887: Albert A. Michelson and Edward W. Morley: Michelson–Morley experiment which showed a lack of evidence for the aether.

- 1888: Friedrich Reinitzer discovers liquid crystals.

- 1892: Dmitri Ivanovsky discovers viruses.

- 1895: Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovers x-rays.

- 1896: Henri Becquerel discovers radioactivity

- 1896: Svante Arrhenius derives the basic principles of the greenhouse effect

- 1897: J.J. Thomson discovers the electron in cathode rays

- 1898: Martinus Beijerinck: concluded that a virus is infectious—replicating in the host—and thus not a mere toxin, and gave it the name "virus"

- 1898: J.J. Thomson proposed the plum pudding model of an atom

- 1898: Marie Curie discovered radium and polonium

- 1898: J. J. O'Donnell discovers and documents the order-of-sequence for the sound of an approaching tornado

1900–1949

- 1900: Max Planck: explains the emission spectrum of a black body

- 1905: Albert Einstein: theory of special relativity, explanation of Brownian motion, and photoelectric effect

- 1906: Walther Nernst: Third law of thermodynamics

- 1907: Alfred Bertheim: Arsphenamine, the first modern chemotherapeutic agent

- 1909: Fritz Haber: Haber Process for industrial production of ammonia

- 1909: Robert Andrews Millikan: conducts the oil drop experiment and determines the charge on an electron

- 1910: Williamina Fleming: the first white dwarf, 40 Eridani B

- 1911: Ernest Rutherford: Atomic nucleus

- 1911: Heike Kamerlingh Onnes: Superconductivity

- 1912: Alfred Wegener: Continental drift

- 1912: Max von Laue: x-ray diffraction

- 1912: Vesto Slipher: galactic redshifts

- 1912: Henrietta Swan Leavitt: Cepheid variable period-luminosity relation

- 1913: Henry Moseley: defined atomic number

- 1913: Niels Bohr: Model of the atom

- 1915: Albert Einstein: theory of general relativity – also David Hilbert

- 1915: Karl Schwarzschild: discovery of the Schwarzschild radius leading to the identification of black holes

- 1918: Emmy Noether: Noether's theorem – conditions under which the conservation laws are valid

- 1920: Arthur Eddington: Stellar nucleosynthesis

- 1922: Frederick Banting, Charles Best, James Collip, John Macleod: isolation and production of insulin to control diabetes

- 1924: Wolfgang Pauli: quantum Pauli exclusion principle

- 1924: Edwin Hubble: the discovery that the Milky Way is just one of many galaxies

- 1925: Erwin Schrödinger: Schrödinger equation (Quantum mechanics)

- 1925: Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin: Discovery of the composition of the Sun and that hydrogen is the most abundant element in the Universe

- 1927: Werner Heisenberg: Uncertainty principle (Quantum mechanics)

- 1927: Georges Lemaître: Theory of the Big Bang

- 1928: Paul Dirac: Dirac equation (Quantum mechanics)

- 1929: Edwin Hubble: Hubble's law of the expanding universe

- 1929: Alexander Fleming: Penicillin, the first beta-lactam antibiotic

- 1929: Lars Onsager's reciprocal relations, a potential fourth law of thermodynamics

- 1930: Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar discovers his eponymous limit of the maximum mass of a white dwarf star

- 1931: Kurt Gödel: incompleteness theorems prove formal axiomatic systems are incomplete

- 1932: James Chadwick: Discovery of the neutron

- 1932: Karl Guthe Jansky discovers the first astronomical radio source, Sagittarius A

- 1932: Ernest Walton and John Cockcroft: Nuclear fission by proton bombardment

- 1934: Enrico Fermi: Nuclear fission by neutron irradiation

- 1934: Clive McCay: Calorie restriction extends the maximum lifespan of another species

- 1938: Otto Hahn, Lise Meitner and Fritz Strassmann: Nuclear fission of heavy nuclei

- 1938: Isidor Rabi: Nuclear magnetic resonance

- 1943: Oswald Avery proves that DNA is the genetic material of the chromosome

- 1945: Howard Florey Mass production of penicillin

- 1947: William Shockley, John Bardeen and Walter Brattain invent the first transistor

- 1948: Claude Elwood Shannon: 'A mathematical theory of communication' a seminal paper in Information theory.

- 1948: Richard Feynman, Julian Schwinger, Sin-Itiro Tomonaga and Freeman Dyson: Quantum electrodynamics

1950–1999

- 1951: George Otto Gey propagates first cancer cell line, HeLa

- 1952: Jonas Salk: developed and tested first polio vaccine

- 1952: Stanley Miller: demonstrated that the building blocks of life could arise from primeval soup in the conditions present during early Earth (Miller-Urey experiment)

- 1952: Frederick Sanger: demonstrated that proteins are sequences of amino acids

- 1953: James Watson, Francis Crick, Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin: helical structure of DNA, basis for molecular biology

- 1957: Chien Shiung Wu: demonstrated that parity, and thus charge conjugation and time-reversals, are violated for weak interactions

- 1962: Riccardo Giacconi and his team discover the first cosmic x-ray source, Scorpius X-1

- 1963: Lawrence Morley, Fred Vine, and Drummond Matthews: Paleomagnetic stripes in ocean crust as evidence of plate tectonics (Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis).

- 1964: Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig: postulates quarks, leading to the standard model

- 1964: Arno Penzias and Robert Woodrow Wilson: detection of CMBR providing experimental evidence for the Big Bang

- 1965: Leonard Hayflick: normal cells divide only a certain number of times: the Hayflick limit

- 1967: Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Antony Hewish discover first pulsar

- 1967: Vela nuclear test detection satellites discover the first gamma-ray burst

- 1970: James H. Ellis proposed the possibility of "non-secret encryption", more commonly termed public-key cryptography, a concept that would be implemented by his GCHQ colleague Clifford Cocks in 1973, in what would become known as the RSA algorithm, with key exchange added by a third colleague Malcolm J. Williamson, in 1975.

- 1971: Place cells in the brain are discovered by John O'Keefe

- 1974: Russell Alan Hulse and Joseph Hooton Taylor, Jr. discover indirect evidence for gravitational wave radiation in the Hulse–Taylor binary

- 1977: Frederick Sanger sequences the first DNA genome of an organism using Sanger sequencing

- 1980: Klaus von Klitzing discovered the quantum Hall effect

- 1982: Donald C. Backer et al. discover the first millisecond pulsar

- 1983: Kary Mullis invents the polymerase chain reaction, a key discovery in molecular biology

- 1986: Karl Müller and Johannes Bednorz: Discovery of High-temperature superconductivity

- 1988: Template:Ill and colleagues at TU Delft and Philips Research discovered the quantized conductance in a two-dimensional electron gas.

- 1990: Mary-Claire King discovers the link between heritable breast cancers and a gene found on chromosome 17q21.[127][128]

- 1992: Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail observe the first pulsar planets (this was the first confirmed discovery of planets outside the Solar System)

- 1994: Andrew Wiles proves Fermat's Last Theorem

- 1995: Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz definitively observe the first extrasolar planet around a main sequence star

- 1995: Eric Cornell, Carl Wieman and Wolfgang Ketterle attained the first Bose-Einstein Condensate with atomic gases, so called fifth state of matter at an extremely low temperature.

- 1996: Roslin Institute: Dolly the sheep was cloned.[129]

- 1997: CDF and DØ experiments at Fermilab: Top quark.

- 1998: Supernova Cosmology Project and the High-Z Supernova Search Team: discovery of the accelerated expansion of the Universe and dark energy

- 2000: The Tau neutrino is discovered by the DONUT collaboration

21st century

- 2001: The first draft of the Human Genome Project is published.[130]

- 2003: Grigori Perelman presents proof of the Poincaré Conjecture.

- 2003: The Human Genome Project sequences the human genome with a 92% accuracy.[131]

- 2004: Ben Green and Terence Tao announce their proof on arithmetic progressions in prime numbers known as the Green–Tao Theorem.

- 2004: Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov isolated graphene, a monolayer of carbon atoms, and studied its quantum electrical properties.

- 2005: Grid cells in the brain are discovered by Edvard Moser and May-Britt Moser.

- 2010: The first self-replicating, synthetic bacterial cells are constructed.[132]

- 2010: The Neanderthal Genome Project presented preliminary genetic evidence that interbreeding likely occurred and that a small but significant portion of Neanderthal admixture is present in modern non-African populations.[133]

- 2012: Higgs boson is discovered at CERN (confirmed to 99.999% certainty)

- 2012: Photonic molecules are discovered at MIT

- 2014: Exotic hadrons are discovered at the LHCb

- 2014: Photonic metamaterials are discovered to make passive daytime radiative cooling possible by Raman et al.[134][135]

- 2016: The LIGO team detects gravitational waves from a black hole merger

- 2017: Gravitational wave signal GW170817 is observed by the LIGO/Virgo collaboration. This is the first instance of a gravitational wave event observed to have a simultaneous electromagnetic signal when space telescopes like Hubble observed lights coming from the event, thereby marking a significant breakthrough for multi-messenger astronomy.[136][137][138]

- 2019: The first image of a black hole is captured, using eight different telescopes taking simultaneous pictures, timed with extremely precise atomic clocks. [1]

- 2020: NASA and SOFIA (Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy) discover about Template:Convert of surface water in one of the Moon's largest visible craters.[139]

- 2022: The standard reference gene, GRCh38.p14, of the human genome, is fully sequenced and contains 3.1 billion base pairs.[140]

References

External links

Template:History of science Template:Portal bar

- ↑ Template:Cite encyclopedia

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Richard J. Gillings, Mathematics in the Time of the Pharaohs, Dover, New York, 1982, 161.

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Template:Cite book Alt URL

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal.

- ↑ Template:Cite magazine

- ↑ Bold, Benjamin. Famous Problems of Geometry and How to Solve Them, Dover Publications, 1982 (orig. 1969).

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Bhate, S. and Kak, S. (1993) Panini and Computer Science. Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, vol. 72, pp. 79-94.

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Harvnb. "It was consequently a signal achievement on the part of Menaechmus when he disclosed that curves having the desired property were near at hand. In fact, there was a family of appropriate curves obtained from a single source – the cutting of a right circular cone by a plane perpendicular to an element of the cone. That is, Menaechmus is reputed to have discovered the curves that were later known as the ellipse, the parabola, and the hyperbola. [...] Yet the first discovery of the ellipse seems to have been made by Menaechmus as a mere by-product in a search in which it was the parabola and hyperbola that proffered the properties needed in the solution of the Delian problem."

- ↑ Template:Harvnb. "Menaechmus apparently derived these properties of the conic sections and others as well. Since this material has a strong resemblance to the use of coordinates, as illustrated above, it has sometimes been maintained that Menaechmus had analytic geometry. Such a judgment is warranted only in part, for certainly Menaechmus was unaware that any equation in two unknown quantities determines a curve. In fact, the general concept of an equation in unknown quantities was alien to Greek thought. It was shortcomings in algebraic notations that, more than anything else, operated against the Greek achievement of a full-fledged coordinate geometry."

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Template:Harvnb. "Trigonometry, like other branches of mathematics, was not the work of any one man, or nation. Theorems on ratios of the sides of similar triangles had been known to, and used by, the ancient Egyptians and Babylonians. In view of the pre-Hellenic lack of the concept of angle measure, such a study might better be called "trilaterometry", or the measure of three sided polygons (trilaterals), than "trigonometry", the measure of parts of a triangle. With the Greeks we first find a systematic study of relationships between angles (or arcs) in a circle and the lengths of chords subtending these. Properties of chords, as measures of central and inscribed angles in circles, were familiar to the Greeks of Hippocrates' day, and it is likely that Eudoxus had used ratios and angle measures in determining the size of the earth and the relative distances of the sun and the moon. In the works of Euclid there is no trigonometry in the strict sense of the word, but there are theorems equivalent to specific trigonometric laws or formulas. Propositions II.12 and 13 of the Elements, for example, are the laws of cosines for obtuse and acute angles respectively, stated in geometric rather than trigonometric language and proved by a method similar to that used by Euclid in connection with the Pythagorean theorem. Theorems on the lengths of chords are essentially applications of the modern law of sines. We have seen that Archimedes' theorem on the broken chord can readily be translated into trigonometric language analogous to formulas for sines of sums and differences of angles."

- ↑ Ian Bruce (2000) "Napier’s Logarithms", American Journal of Physics 68(2):148

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ A. W. F. Edwards. Pascal's arithmetical triangle: the story of a mathematical idea. JHU Press, 2002. Pages 30–31.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Archimedes, The Method of Mechanical Theorems; see Archimedes Palimpsest

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Harvnb. "Greek mathematics sometimes has been described as essentially static, with little regard for the notion of variability; but Archimedes, in his study of the spiral, seems to have found the tangent to a curve through kinematic considerations akin to differential calculus. Thinking of a point on the spiral 1=r = aθ as subjected to a double motion — a uniform radial motion away from the origin of coordinates and a circular motion about the origin — he seems to have found (through the parallelogram of velocities) the direction of motion (hence of the tangent to the curve) by noting the resultant of the two component motions. This appears to be the first instance in which a tangent was found to a curve other than a circle.

Archimedes' study of the spiral, a curve that he ascribed to his friend Conon of Alexandria, was part of the Greek search for the solution of the three famous problems." - ↑ D. Rawlins: "Methods for Measuring the Earth's Size by Determining the Curvature of the Sea" and "Racking the Stade for Eratosthenes", appendices to "The Eratosthenes–Strabo Nile Map. Is It the Earliest Surviving Instance of Spherical Cartography? Did It Supply the 5000 Stades Arc for Eratosthenes' Experiment?", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, v.26, 211–219, 1982

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Bowen A.C., Goldstein B.R. (1991). "Hipparchus' Treatment of Early Greek Astronomy: The Case of Eudoxus and the Length of Daytime Author(s)". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 135(2): 233–254.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth (Vol. 3), p 24. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Harvnb. "In Book I of this treatise Menelaus establishes a basis for spherical triangles analogous to that of Euclid I for plane triangles. Included is a theorem without Euclidean analogue – that two spherical triangles are congruent if corresponding angles are equal (Menelaus did not distinguish between congruent and symmetric spherical triangles); and the theorem A + B + C > 180° is established. The second book of the Sphaerica describes the application of spherical geometry to astronomical phenomena and is of little mathematical interest. Book III, the last, contains the well known "theorem of Menelaus" as part of what is essentially spherical trigonometry in the typical Greek form – a geometry or trigonometry of chords in a circle. In the circle in Fig. 10.4 we should write that chord AB is twice the sine of half the central angle AOB (multiplied by the radius of the circle). Menelaus and his Greek successors instead referred to AB simply as the chord corresponding to the arc AB. If BOB' is a diameter of the circle, then chord A' is twice the cosine of half the angle AOB (multiplied by the radius of the circle)."

- ↑ Kurt Vogel, "Diophantus of Alexandria." in Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Encyclopedia.com, 2008. Quote: The symbolism that Diophantus introduced for the first time, and undoubtedly devised himself, provided a short and readily comprehensible means of expressing an equation... Since an abbreviation is also employed for the word ‘equals’, Diophantus took a fundamental step from verbal algebra towards symbolic algebra.

- ↑ * Struik, Dirk J. (1987). A Concise History of Mathematics. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 32–33. "In these matrices we find negative numbers, which appear here for the first time in history."

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Reimer, L., and Reimer, W. Mathematicians Are People, Too: Stories from the Lives of Great Mathematicians, Vol. 2. 1995. pp. 22-22. Parsippany, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. as Dale Seymor Publications. Template:ISBN.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Hayashi (2008), Aryabhata I.Template:Full citation needed

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Template:Harvnb. "He gave more elegant rules for the sum of the squares and cubes of an initial segment of the positive integers. The sixth part of the product of three quantities consisting of the number of terms, the number of terms plus one, and twice the number of terms plus one is the sum of the squares. The square of the sum of the series is the sum of the cubes."

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Britannica

- ↑ Template:Cite arXiv

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ The concept of Indian heliocentrism has been advocated by B. L. van der Waerden, Das heliozentrische System in der griechischen, persischen und indischen Astronomie. Naturforschenden Gesellschaft in Zürich. Zürich:Kommissionsverlag Leeman AG, 1970.

- ↑ B.L. van der Waerden, "The Heliocentric System in Greek, Persian and Hindu Astronomy", in David A. King and George Saliba, ed., From Deferent to Equant: A Volume of Studies in the History of Science in the Ancient and Medieval Near East in Honor of E. S. Kennedy, Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 500 (1987), pp. 529–534.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Noel Swerdlow, "Review: A Lost Monument of Indian Astronomy," Isis, 64 (1973): 239–243.

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Morris R. Cohen and I. E. Drabkin (eds. 1958), A Source Book in Greek Science (p. 220), with several changes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, as referenced by David C. Lindberg (1992), The Beginnings of Western Science: The European Scientific Tradition in Philosophical, Religious, and Institutional Context, 600 B.C. to A.D. 1450, University of Chicago Press, p. 305, Template:ISBN

- Note the influence of Philoponus' statement on Galileo's Two New Sciences (1638)

- ↑ Henry Thomas Colebrooke. Algebra, with Arithmetic and Mensuration, from the Sanscrit of Brahmegupta and Bháscara, London 1817, p. 339 (online)

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Template:Citation

- ↑ Bina Chatterjee (introduction by), The Khandakhadyaka of Brahmagupta, Motilal Banarsidass (1970), p. 13

- ↑ Lallanji Gopal, History of Agriculture in India, Up to C. 1200 A.D., Concept Publishing Company (2008), p. 603

- ↑ Kosla Vepa, Astronomical Dating of Events & Select Vignettes from Indian History, Indic Studies Foundation (2008), p. 372

- ↑ Dwijendra Narayan Jha (edited by), The feudal order: state, society, and ideology in early medieval India, Manohar Publishers & Distributors (2000), p. 276

- ↑ http://spie.org/etop/2007/etop07fundamentalsII.pdf," R. Rashed credited Ibn Sahl with discovering the law of refraction [23], usually called Snell’s law and also Snell and Descartes’ law."

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Florian Cajori (1918), Origin of the Name "Mathematical Induction", The American Mathematical Monthly 25 (5), p. 197-201.

- ↑ Crombie, Alistair Cameron, Augustine to Galileo 2, p. 67.

- ↑ Template:Cite encyclopedia

(cf. Abel B. Franco (October 2003). "Avempace, Projectile Motion, and Impetus Theory", Journal of the History of Ideas 64 (4), p. 521-546 [528].) - ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Mochrie, Robert (2005). Justice in Exchange: The Economic Philosophy of John Duns ScotusTemplate:Dead link

- ↑ 110.0 110.1 Victor J. Katz (1995). "Ideas of Calculus in Islam and India", Mathematics Magazine 68 (3), pp. 163–174.

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Ian G. Pearce (2002). Madhava of Sangamagramma. MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St Andrews.

- ↑ Radha Charan Gupta (1977) "Parameshvara's rule for the circumradius of a cyclic quadrilateral", Historia Mathematica 4: 67–74

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Robert Recorde, The Whetstone of Witte (London, England: John Kyngstone, 1557), p. 236 (although the pages of this book are not numbered). From the chapter titled "The rule of equation, commonly called Algebers Rule" (p. 236): "Howbeit, for easie alteration of equations. I will propounde a fewe examples, bicause the extraction of their rootes, maie the more aptly bee wroughte. And to avoide the tediouse repetition of these woordes: is equalle to: I will sette as I doe often in worke use, a paire of paralleles, or Gemowe [twin, from gemew, from the French gemeau (twin / twins), from the Latin gemellus (little twin)] lines of one lengthe, thus: = , bicause noe .2. thynges, can be moare equalle." (However, for easy manipulation of equations, I will present a few examples in order that the extraction of roots may be more readily done. And to avoid the tedious repetition of these words "is equal to", I will substitute, as I often do when working, a pair of parallels or twin lines of the same length, thus: = , because no two things can be more equal.)

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Hurst, Jillian H. “Pioneering Geneticist Mary-Claire King Receives the 2014 Lasker~koshland Special Achievement Award in Medical Science.” The Journal of Clinical Investigation, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 8 Sept. 2014.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web