Tetration

Template:Short description Template:Distinguish Template:For Template:Use dmy dates

In mathematics, tetration (or hyper-4) is an operation based on iterated, or repeated, exponentiation. There is no standard notation for tetration, though Knuth's up arrow notation and the left-exponent are common.

Under the definition as repeated exponentiation, means , where Template:Mvar copies of Template:Mvar are iterated via exponentiation, right-to-left, i.e. the application of exponentiation times. Template:Mvar is called the "height" of the function, while Template:Mvar is called the "base," analogous to exponentiation. It would be read as "the Template:Mvarth tetration of Template:Mvar". For example, 2 tetrated to 4 (or the fourth tetration of 2) is .

It is the next hyperoperation after exponentiation, but before pentation. The word was coined by Reuben Louis Goodstein from tetra- (four) and iteration.

Tetration is also defined recursively as

allowing for attempts to extend tetration to non-natural numbers such as real, complex, and ordinal numbers.

The two inverses of tetration are called super-root and super-logarithm, analogous to the nth root and the logarithmic functions. None of the three functions are elementary.

Tetration is used for the notation of very large numbers.

Introduction

The first four hyperoperations are shown here, with tetration being considered the fourth in the series. The unary operation succession, defined as , is considered to be the zeroth operation.

- Addition Template:Mvar copies of 1 added to Template:Mvar combined by succession.

- Multiplication Template:Mvar copies of Template:Mvar combined by addition.

- Exponentiation Template:Mvar copies of Template:Mvar combined by multiplication.

- Tetration Template:Mvar copies of Template:Mvar combined by exponentiation, right-to-left.

Importantly, nested exponents are interpreted from the top down: Template:Tmath means Template:Tmath and not Template:Tmath

Succession, , is the most basic operation; while addition () is a primary operation, for addition of natural numbers it can be thought of as a chained succession of successors of ; multiplication () is also a primary operation, though for natural numbers it can analogously be thought of as a chained addition involving numbers of . Exponentiation can be thought of as a chained multiplication involving numbers of and tetration () as a chained power involving numbers . Each of the operations above are defined by iterating the previous one;[1] however, unlike the operations before it, tetration is not an elementary function.

The parameter is referred to as the base, while the parameter may be referred to as the height. In the original definition of tetration, the height parameter must be a natural number; for instance, it would be illogical to say "three raised to itself negative five times" or "four raised to itself one half of a time." However, just as addition, multiplication, and exponentiation can be defined in ways that allow for extensions to real and complex numbers, several attempts have been made to generalize tetration to negative numbers, real numbers, and complex numbers. One such way for doing so is using a recursive definition for tetration; for any positive real and non-negative integer , we can define recursively as:[1]

The recursive definition is equivalent to repeated exponentiation for natural heights; however, this definition allows for extensions to the other heights such as , , and as well – many of these extensions are areas of active research.

Terminology

There are many terms for tetration, each of which has some logic behind it, but some have not become commonly used for one reason or another. Here is a comparison of each term with its rationale and counter-rationale.

- The term tetration, introduced by Goodstein in his 1947 paper Transfinite Ordinals in Recursive Number Theory[2] (generalizing the recursive base-representation used in Goodstein's theorem to use higher operations), has gained dominance. It was also popularized in Rudy Rucker's Infinity and the Mind.

- The term superexponentiation was published by Bromer in his paper Superexponentiation in 1987.[3] It was used earlier by Ed Nelson in his book Predicative Arithmetic, Princeton University Press, 1986.

- The term hyperpower[4] is a natural combination of hyper and power, which aptly describes tetration. The problem lies in the meaning of hyper with respect to the hyperoperation sequence. When considering hyperoperations, the term hyper refers to all ranks, and the term super refers to rank 4, or tetration. So under these considerations hyperpower is misleading, since it is only referring to tetration.

- The term power tower[5] is occasionally used, in the form "the power tower of order Template:Mvar" for . Exponentiation is easily misconstrued: note that the operation of raising to a power is right-associative (see below). Tetration is iterated exponentiation (call this right-associative operation ^), starting from the top right side of the expression with an instance a^a (call this value c). Exponentiating the next leftward a (call this the 'next base' b), is to work leftward after obtaining the new value b^c. Working to the left, use the next a to the left, as the base b, and evaluate the new b^c. 'Descend down the tower' in turn, with the new value for c on the next downward step.

Owing in part to some shared terminology and similar notational symbolism, tetration is often confused with closely related functions and expressions. Here are a few related terms:

| Terminology | Form |

|---|---|

| Tetration | |

| Iterated exponentials | |

| Nested exponentials (also towers) | |

| Infinite exponentials (also towers) |

In the first two expressions Template:Mvar is the base, and the number of times Template:Mvar appears is the height (add one for Template:Mvar). In the third expression, Template:Mvar is the height, but each of the bases is different.

Care must be taken when referring to iterated exponentials, as it is common to call expressions of this form iterated exponentiation, which is ambiguous, as this can either mean iterated powers or iterated exponentials.

Notation

There are many different notation styles that can be used to express tetration. Some notations can also be used to describe other hyperoperations, while some are limited to tetration and have no immediate extension.

| Name | Form | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Knuth's up-arrow notation | Allows extension by putting more arrows, or, even more powerfully, an indexed arrow. | |

| Conway chained arrow notation | Allows extension by increasing the number 2 (equivalent with the extensions above), but also, even more powerfully, by extending the chain. | |

| Ackermann function | Allows the special case to be written in terms of the Ackermann function. | |

| Iterated exponential notation | Allows simple extension to iterated exponentials from initial values other than 1. | |

| Hooshmand notations[6] | Used by M. H. Hooshmand [2006]. | |

| Hyperoperation notations | Allows extension by increasing the number 4; this gives the family of hyperoperations. | |

| Double caret notation | Template:Code | Since the up-arrow is used identically to the caret (^), tetration may be written as (^^); convenient for ASCII.

|

One notation above uses iterated exponential notation; this is defined in general as follows:

- with Template:Mvar Template:Mvars.

There are not as many notations for iterated exponentials, but here are a few:

| Name | Form | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Standard notation | Euler coined the notation , and iteration notation has been around about as long. | |

| Knuth's up-arrow notation | Allows for super-powers and super-exponential function by increasing the number of arrows; used in the article on large numbers. | |

| Text notation | Template:Code | Based on standard notation; convenient for ASCII. |

| J Notation | Template:Code | Repeats the exponentiation. See J (programming language)[7] |

| Infinity barrier notation | Jonathan Bowers coined this,[8] and it can be extended to higher hyper-operations |

Examples

Because of the extremely fast growth of tetration, most values in the following table are too large to write in scientific notation. In these cases, iterated exponential notation is used to express them in base 10. The values containing a decimal point are approximate. Usually, the limit that can be calculated in a numerical calculation program such as Wolfram Alpha is 3↑↑4, and the number of digits up to 3↑↑5 can be expressed.

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 (2Template:Sup) | 16 (2Template:Sup) | 65,536 (2Template:Sup) | 2.00353 × 10Template:Sup | (10Template:Sup) | |

| 3 | 27 (3Template:Sup) | 7,625,597,484,987 (3Template:Sup) | 1.25801 × 10Template:Sup [9] |

(10Template:Sup) |

||

| 4 | 256 (4Template:Sup) | 1.34078 × 10Template:Sup (4Template:Sup) | (10Template:Sup) | |||

| 5 | 3,125 (5Template:Sup) | 1.91101 × 10Template:Sup (5Template:Sup) | (10Template:Sup) | |||

| 6 | 46,656 (6Template:Sup) | 2.65912 × 10Template:Sup (6Template:Sup) | (10Template:Sup) | |||

| 7 | 823,543 (7Template:Sup) | 3.75982 × 10Template:Sup (7823,543) | (3.17742 × 10Template:Sup digits) | |||

| 8 | 16,777,216 (8Template:Sup) | 6.01452 × 10Template:Sup | (5.43165 × 10Template:Sup digits) | |||

| 9 | 387,420,489 (9Template:Sup) | 4.28125 × 10Template:Sup | (4.08535 × 10Template:Sup digits) | |||

| 10 | 10,000,000,000 (10Template:Sup) | 10Template:Sup | (10Template:Sup + 1 digits) |

Remark: If Template:Mvar does not differ from 10 by orders of magnitude, then for all . For example, in the above table, and the difference is even smaller for the following rows.

Extensions

Tetration can be extended in two different ways; in the equation , both the base Template:Mvar and the height Template:Mvar can be generalized using the definition and properties of tetration. Although the base and the height can be extended beyond the non-negative integers to different domains, including , complex functions such as , and heights of infinite Template:Mvar, the more limited properties of tetration reduce the ability to extend tetration.

Extension of domain for bases

Base zero

The exponential is not consistently defined. Thus, the tetrations are not clearly defined by the formula given earlier. However, is well defined, and exists:[10]

Thus we could consistently define . This is analogous to defining .

Under this extension, , so the rule from the original definition still holds.

Complex bases

Since complex numbers can be raised to powers, tetration can be applied to bases of the form Template:Math (where Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar are real). For example, in Template:Math with Template:Math, tetration is achieved by using the principal branch of the natural logarithm; using Euler's formula we get the relation:

This suggests a recursive definition for Template:Math given any Template:Math:

The following approximate values can be derived:

| Approximate value | |

|---|---|

| Template:Math | |

| Template:Math | |

| Template:Math | |

| Template:Math | |

| Template:Math | |

| Template:Math | |

| Template:Math | |

| Template:Math | |

| Template:Math |

Solving the inverse relation, as in the previous section, yields the expected Template:Math and Template:Math, with negative values of Template:Mvar giving infinite results on the imaginary axis.Template:Citation needed Plotted in the complex plane, the entire sequence spirals to the limit Template:Math, which could be interpreted as the value where Template:Mvar is infinite.

Such tetration sequences have been studied since the time of Euler, but are poorly understood due to their chaotic behavior. Most published research historically has focused on the convergence of the infinitely iterated exponential function. Current research has greatly benefited by the advent of powerful computers with fractal and symbolic mathematics software. Much of what is known about tetration comes from general knowledge of complex dynamics and specific research of the exponential map.Template:Citation needed

Extensions of the domain for different heights

Infinite heights

Tetration can be extended to infinite heights; i.e., for certain Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar values in , there exists a well defined result for an infinite Template:Mvar. This is because for bases within a certain interval, tetration converges to a finite value as the height tends to infinity. For example, converges to 2, and can therefore be said to be equal to 2. The trend towards 2 can be seen by evaluating a small finite tower:

In general, the infinitely iterated exponential , defined as the limit of as Template:Mvar goes to infinity, converges for Template:Math, roughly the interval from 0.066 to 1.44, a result shown by Leonhard Euler.[11] The limit, should it exist, is a positive real solution of the equation Template:Math. Thus, Template:Math. The limit defining the infinite exponential of Template:Mvar does not exist when Template:Math because the maximum of Template:Math is Template:Math. The limit also fails to exist when Template:Math.

This may be extended to complex numbers Template:Mvar with the definition:

where Template:Math represents Lambert's W function.

As the limit Template:Math (if existent on the positive real line, i.e. for Template:Math) must satisfy Template:Math we see that Template:Math is (the lower branch of) the inverse function of Template:Math.

Negative heights

We can use the recursive rule for tetration,

to prove :

Substituting −1 for Template:Mvar gives

- .[12]

Smaller negative values cannot be well defined in this way. Substituting −2 for Template:Mvar in the same equation gives

which is not well defined. They can, however, sometimes be considered sets.[12]

For , any definition of is consistent with the rule because

- for any .

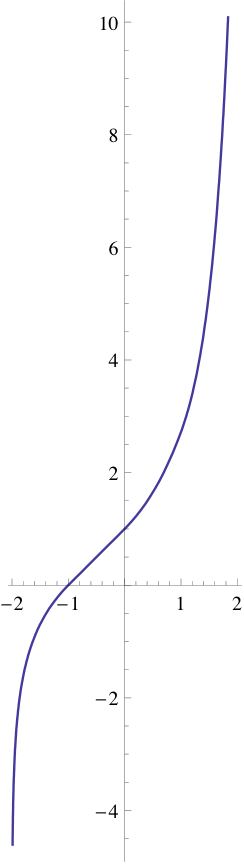

Linear approximation for real heights

A linear approximation (solution to the continuity requirement, approximation to the differentiability requirement) is given by:

hence:

| Approximation | Domain |

|---|---|

| for Template:Math | |

| for Template:Math | |

| for Template:Math |

and so on. However, it is only piecewise differentiable; at integer values of Template:Mvar the derivative is multiplied by . It is continuously differentiable for if and only if . For example, using these methods and

A main theorem in Hooshmand's paper[6] states: Let . If is continuous and satisfies the conditions:

- is differentiable on Template:Open-open,

- is a nondecreasing or nonincreasing function on Template:Open-open,

then is uniquely determined through the equation

where denotes the fractional part of Template:Mvar and is the -iterated function of the function .

The proof is that the second through fourth conditions trivially imply that Template:Mvar is a linear function on Template:Closed-closed.

The linear approximation to natural tetration function is continuously differentiable, but its second derivative does not exist at integer values of its argument. Hooshmand derived another uniqueness theorem for it which states:

If is a continuous function that satisfies:

- is convex on Template:Open-open,

then . [Here is Hooshmand's name for the linear approximation to the natural tetration function.]

The proof is much the same as before; the recursion equation ensures that and then the convexity condition implies that is linear on Template:Open-open.

Therefore, the linear approximation to natural tetration is the only solution of the equation and which is convex on Template:Open-open. All other sufficiently-differentiable solutions must have an inflection point on the interval Template:Open-open.

Higher order approximations for real heights

Beyond linear approximations, a quadratic approximation (to the differentiability requirement) is given by:

which is differentiable for all , but not twice differentiable. For example, If this is the same as the linear approximation.[1]

Because of the way it is calculated, this function does not "cancel out", contrary to exponents, where . Namely,

- .

Just as there is a quadratic approximation, cubic approximations and methods for generalizing to approximations of degree Template:Mvar also exist, although they are much more unwieldy.[1][13]

Complex heights

In 2017, it was proven[14] that there exists a unique function Template:Mvar which is a solution of the equation Template:Math and satisfies the additional conditions that Template:Math and Template:Math approaches the fixed points of the logarithm (roughly Template:Math) as Template:Mvar approaches Template:Math and that Template:Mvar is holomorphic in the whole complex Template:Mvar-plane, except the part of the real axis at Template:Math. This proof confirms a previous conjecture.[15] The construction of such a function was originally demonstrated by Kneser in 1950.[16] The complex map of this function is shown in the figure at right. The proof also works for other bases besides e, as long as the base is greater than . Subsequent work extended the construction to all complex bases.[17]

The requirement of the tetration being holomorphic is important for its uniqueness. Many functions Template:Mvar can be constructed as

where Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar are real sequences which decay fast enough to provide the convergence of the series, at least at moderate values of Template:Math.

The function Template:Mvar satisfies the tetration equations Template:Math, Template:Math, and if Template:Math and Template:Math approach 0 fast enough it will be analytic on a neighborhood of the positive real axis. However, if some elements of Template:Math or Template:Math are not zero, then function Template:Mvar has multitudes of additional singularities and cutlines in the complex plane, due to the exponential growth of sin and cos along the imaginary axis; the smaller the coefficients Template:Math and Template:Math are, the further away these singularities are from the real axis.

The extension of tetration into the complex plane is thus essential for the uniqueness; the real-analytic tetration is not unique.

Ordinal tetration

Tetration can be defined for ordinal numbers via transfinite induction. For all Template:Math and all Template:Math:

Non-elementary recursiveness

Tetration (restricted to ) is not an elementary recursive function. One can prove by induction that for every elementary recursive function Template:Mvar, there is a constant Template:Mvar such that

We denote the right hand side by . Suppose on the contrary that tetration is elementary recursive. is also elementary recursive. By the above inequality, there is a constant Template:Mvar such that . By letting , we have that , a contradiction.

Inverse operations

Exponentiation has two inverse operations; roots and logarithms. Analogously, the inverses of tetration are often called the super-root, and the super-logarithm (In fact, all hyperoperations greater than or equal to 3 have analogous inverses); e.g., in the function , the two inverses are the cube super-root of Template:Mvar and the super-logarithm base Template:Mvar of Template:Mvar.

Super-root

Template:Redirect The super-root is the inverse operation of tetration with respect to the base: if , then Template:Mvar is an Template:Mvarth super-root of Template:Mvar ( or ).

For example,

so 2 is the 4th super-root of 65,536 .

Square super-root

The 2nd-order super-root, square super-root, or super square root has two equivalent notations, and . It is the inverse of and can be represented with the Lambert W function:[18]

- or

The function also illustrates the reflective nature of the root and logarithm functions as the equation below only holds true when :

Like square roots, the square super-root of Template:Mvar may not have a single solution. Unlike square roots, determining the number of square super-roots of Template:Mvar may be difficult. In general, if , then Template:Mvar has two positive square super-roots between 0 and 1 calculated using formulas:; and if , then Template:Mvar has one positive square super-root greater than 1 calculated using formulas: . If Template:Mvar is positive and less than it does not have any real square super-roots, but the formula given above yields countably infinitely many complex ones for any finite Template:Mvar not equal to 1.[18] The function has been used to determine the size of data clusters.[19]

At : Template:Center

Other super-roots

One of the simpler and faster formulas for a third-degree super-root is the recursive formula. If then one can use:

For each integer Template:Math, the function Template:Math is defined and increasing for Template:Math, and Template:Math, so that the Template:Mvarth super-root of Template:Mvar, , exists for Template:Math.

However, if the linear approximation above is used, then if Template:Math, so cannot exist.

In the same way as the square super-root, terminology for other super-roots can be based on the normal roots: "cube super-roots" can be expressed as ; the "4th super-root" can be expressed as ; and the "Template:Mvarth super-root" is . Note that may not be uniquely defined, because there may be more than one Template:MvarTemplate:Sup root. For example, Template:Mvar has a single (real) super-root if Template:Mvar is odd, and up to two if Template:Mvar is even.Template:Citation needed

Just as with the extension of tetration to infinite heights, the super-root can be extended to Template:Math, being well-defined if Template:Math. Note that and thus that . Therefore, when it is well defined, and, unlike normal tetration, is an elementary function. For example, .

It follows from the Gelfond–Schneider theorem that super-root for any positive integer Template:Mvar is either integer or transcendental, and is either integer or irrational.[20] It is still an open question whether irrational super-roots are transcendental in the latter case.

Super-logarithm

Template:Main Once a continuous increasing (in Template:Mvar) definition of tetration, Template:Math, is selected, the corresponding super-logarithm or is defined for all real numbers Template:Mvar, and Template:Math.

The function Template:Math satisfies:

Open questions

Other than the problems with the extensions of tetration, there are several open questions concerning tetration, particularly when concerning the relations between number systems such as integers and irrational numbers:

- It is not known whether there is an integer for which Template:Math is an integer, because we could not calculate precisely enough the numbers of digits after the decimal points of .[21]Template:Additional citation needed It is similar for Template:Math for , as we are not aware of any other methods besides some direct computation. In fact, since , then . Given and , then for . It is believed that Template:Math is not an integer for any positive integer Template:Mvar, due to the algebraic independence of , given Schanuel's conjecture.[22]

- It is not known whether Template:Math is rational for any positive integer Template:Mvar and positive non-integer rational Template:Mvar.[20] For example, it is not known whether the positive root of the equation Template:Math is a rational number.Template:Citation needed

- It is not known whether Template:Math or Template:Math (defined using Kneser's extension) are rationals or not.

Applications

For each graph H on h vertices and each Template:Math, define

Then each graph G on n vertices with at most Template:Math copies of H can be made H-free by removing at most Template:Math edges.[23]

See also

Template:Commons category Template:Wiktionary

- Ackermann function

- Big O notation

- Double exponential function

- Hyperoperation

- Iterated logarithm

- Symmetric level-index arithmetic

Notes

References

External Links

- Daniel Geisler, Tetration

- Ioannis Galidakis, On extending hyper4 to nonintegers (undated, 2006 or earlier) (A simpler, easier to read review of the next reference)

- Ioannis Galidakis, On Extending hyper4 and Knuth's Up-arrow Notation to the Reals (undated, 2006 or earlier).

- Robert Munafo, Extension of the hyper4 function to reals (An informal discussion about extending tetration to the real numbers.)

- Lode Vandevenne, Tetration of the Square Root of Two. (2004). (Attempt to extend tetration to real numbers.)

- Ioannis Galidakis, Mathematics, (Definitive list of references to tetration research. Much information on the Lambert W function, Riemann surfaces, and analytic continuation.)

- Joseph MacDonell, Some Critical Points of the Hyperpower Function Template:Webarchive.

- Dave L. Renfro, Web pages for infinitely iterated exponentials

- Template:Cite journal

- Hans Maurer, "Über die Funktion für ganzzahliges Argument (Abundanzen)." Mittheilungen der Mathematische Gesellschaft in Hamburg 4, (1901), p. 33–50. (Reference to usage of from Knobel's paper.)

- The Fourth Operation

- Luca Moroni, The strange properties of the infinite power tower (https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.05559)

Further reading

Template:Hyperoperations Template:Large numbers

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Neyrinck, Mark. An Investigation of Arithmetic Operations. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:MathWorld

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ DiModica, Thomas. Tetration Values. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Euler, L. "De serie Lambertina Plurimisque eius insignibus proprietatibus." Acta Acad. Scient. Petropol. 2, 29–51, 1783. Reprinted in Euler, L. Opera Omnia, Series Prima, Vol. 6: Commentationes Algebraicae. Leipzig, Germany: Teubner, pp. 350–369, 1921. (facsimile)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Andrew Robbins. Solving for the Analytic Piecewise Extension of Tetration and the Super-logarithm. The extensions are found in part two of the paper, "Beginning of Results".

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Krishnam, R. (2004), "Efficient Self-Organization Of Large Wireless Sensor Networks" – Dissertation, BOSTON UNIVERSITY, COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING. pp. 37–40

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Marshall, Ash J., and Tan, Yiren, "A rational number of the form Template:Math with Template:Mvar irrational", Mathematical Gazette 96, March 2012, pp. 106–109.

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Jacob Fox, A new proof of the graph removal lemma, arXiv preprint (2010). arXiv:1006.1300 [math.CO]