General Concept Lattice

The General Concept Lattice (GCL) proposes a novel general construction of concept hierarchy from formal context, where the conventional Formal Concept Lattice based on Formal Concept Analysis (FCA) only serves as a substructure.[1][2][3]

The formal context is a data table of heterogeneous relations illustrating how objects carrying attributes. By analogy with truth-value table, every formal context can develop its fully extended version including all the columns corresponding to attributes constructed, by means of Boolean operations, out of the given attribute set. The GCL is based on the extended formal context which comprehends the full information content of formal context in the sense that it incorporates whatever the formal context should consistently imply. Noteworthily, different formal contexts may give rise to the same extended formal context.[4]

Background

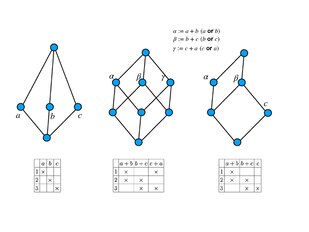

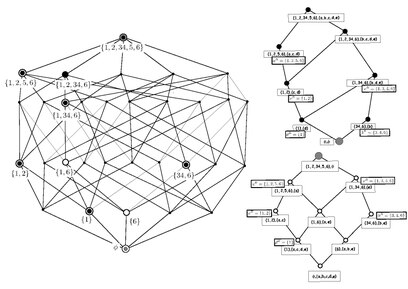

The GCL[4] claims to take into account the extended formal context for preservation of information content. Consider describing a three-ball system (3BS) with three distinct colours, e.g., red, green and blue. Template:AnchorAccording to Table 1, one may refer to different attribute sets, say, , or to reach different formal contexts. The concept hierarchy for the 3BS is supposed to be unique regardless of how the 3BS being described. Template:AnchorHowever, the FCA exhibits different formal concept lattices subject to the chosen formal contexts for the 3BS , see Fig. 1. In contrast, the GCL is an invariant lattice structure with respect to these formal contexts since they can infer each other and ultimately entail the same information content.

| Template:Diagonal split header | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||

In information science, the Formal Concept Analysis (FCA) promises practical applications in various fields based on the following fundamental characteristics.

- It orders the formal concepts in a hierarchy i.e. the formal concept lattice (FCL) which can be visualized as a line diagram that may be helpful for understanding the data.

- Template:AnchorIt enables the attribute exploration,[5] a knowledge acquisition technique based on implications. It is possible to acquire the canonical (Guigues-Duquenne[6]) basis, the non-redundant collection of informative implications based on which valid implications available from the formal context can be derived by the Armstrong rules.

Template:AnchorThe FCL does not appear to be the only lattice applicable to the interpretation of data table. Alternative concept lattices subject to different derivation operators based on the notions relevant to the Rough Set Analysis have also been proposed.[7][8][9] Specifically, the object-oriented concept lattice,[9] which is referred to as the rough set lattice[4] (RSL) afterwards, is found to be particularly instructive to supplement the standard FCA in further understandings of the formal context.

- The FCL exhibits the categorisation for object class according to their common properties while the RSL is according to those properties which other classes do not possess.

- The RSL provides an alternative scheme for implications available from the formal context which are beyond the scope of FCL, as will be clarified later.

Consequently, there are two crucial points to be contemplated.Template:Anchor

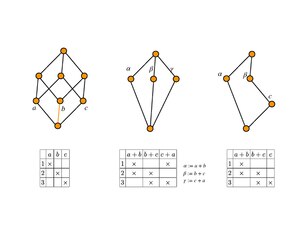

- The FCL and RSL reflect different concept hierarchies interpreting the same formal context in a complementary way. However, similar to the case of FCL, RSL also suffers from different lattice structures varying with respect to the chosen formal contexts, see Fig. 2.

- The implication relations extracted via the RSL from the formal context signify a different part of logic content from the ones extractable via the FCL. The treatment via the RSL would require further efforts of construction, the Guigues-Duquenne basis for the RSL. Moreover, it is unwarranted that the implications of these two together suffices the full logic content.

Fig. 2: Template:AnchorThree different rough set lattices, cf. Fig. 1, obtained from the same three formal contexts describing the 3BS.

The GCL accomplishes a sound theoretical foundation for the concept hierarchies acquired from formal context.[4] Maintaining the generality that preserves the information, the GCL underlies both the FCL and RSL, which correspond to substructures at particular restrictions. Technically, the GCL would be reduced to the FCL and RSL when restricted to conjunctions and disjunctions of elements in the referred attribute set (), respectively. In addition, the GCL unveils extra information complementary to the results via the FCL and RSL. Surprisingly, the implementation of formal context via GCL is much more manageable than those via FCL and RSL.

Related mathematical formulations

Algebras of derivation operators

The derivation operators constitute the building blocks of concept lattices and thus deserve distinctive notations. Subject to a formal context concerning the object set and attribute set ,

are considered as different modal operators[7][8] (Sufficiency, Necessity and Possibility, respectively) that generalise the FCA. For notations, , the operator adopted in the standard FCA,[1][2][3] follows Template:Ill[10] and R. Wille;[1] as well as follows Y. Y. Yao.[9] By , i.e., the object carries the attribute as its property, which is also referred to as where is the set of all objects carrying the attribute .

Template:Anchor With it is straightforward to check that

where the same relations hold if given in terms of .

Two Galois lattices

Galois connections

Template:AnchorFrom the above algebras, there exist different types of Galois connections, e.g.,

(1) , (2)

and (3) that corresponds to (2) when one replaces and . Note that (1) and (2) enable different object-oriented constructions for the concept hierarchies FCL and RSL, respectively. Note that (3) corresponds to the attribute-oriented construction[9] where the roles of object and attribute in the RSL are exchanged. The FCL and RSL apply to different 2-tuple concept collections that manifest different well-defined partial orderings.

Two concept hierarchies

Given as a concept, the 2-tuple is in general constituted by an extent and an intent , which should be distinguished when applied to FCL and RSL. The concept is furnished by based on (1) while is furnished by based on (2). In essence, Template:Anchorthere are two Galois lattices based on different orderings of the two collections of concepts as follows.

entails and since iff , and iff .

entails and since iff , and iff .

Common extents of FCL and RSL

Every attribute listed in the formal context provides an extent for FCL and RSL simultaneously via the object set carrying the attribute. Though the extents for FCL and for RSL do not coincide totally, every for is known to be a common extent of FCL and RSL. This turns up from the main results in FCL (Template:Ill) and RSL: every () is an extent for FCL[1][2][3] and is an extent for RSL.[9] Note that[4] choosing gives rise to .

Two types of informative implications

The consideration of the attribute set-to-set implication () via FCL has an intuitive interpretation:[6] every object possessing all the attributes in possesses all the attributes in , in other words . Alternatively, one may consider based on the RSL in a similar manner:[4] the set of all objects carrying any of the attributes in is contained in the set of all objects carrying any of the attributes in , in other words . It is apparent that and relate different pairs of attribute sets and are incapable of expressing each other.

Extension of formal context

For every formal context one may acquire its extended version deduced in the sense of completing a truth-value table. It is instructive to explicitly label the object/attribute dependence for the formal context,[4] say, rather than since one may have to investigate more than one formal contexts. As is illustrated in Table 1, can be employed to deduce the extended version , where is the set of all attributes constructed out of elements in by means of Boolean operations. Note that includes three columns reflecting the use of and the attribute set .

Obtaining the general concept lattice

Observations based on mathematical facts

Intents in terms of single attributes

The FCL and RSL will not be altered if their intents are interpreted as single attributes.[4]

can be understood as with (the conjunction of all elements in ), plays the role of since .

can be understood as with (the disjunction of all elements in ), plays the role of since .

Here, the dot product stands for the conjunction (the dots is often omitted for compactness) and the summation the disjunction, which are notations in the Curry-Howard style. Note that the orderings become

and , both are implemented by .

Implications from single attribute to single attribute

Concerning the implications extracted from formal context,

serves as the general form of implication relations available from the formal context, which holds for any pair of fulfilling .

Note that turns out to be trivial if , which entails . Intuitively,[4] every object carrying is an object carrying , which means the implication any object having the property must also have the property . In particular,

can be interpreted as with and , can be interpreted as with and ,

where and collapse into .

Lattice of 3-tuple concepts with double Galois connection

When extended to , the algebras of derivation operators remain formally unchanged, apart from the generalisation from to which is signified in terms of[4] the replacements , and . The concepts under consideration become then and , where and , which are constructions allowable by the two Galois connections i.e. and , respectively. Henceforth,

and for , and for .

The extents for the two concepts now coincide exactly. All the attributes in are listed in the formal context , each contributes a common extent for FCL and RSL. Template:AnchorFurthermore, the collection of these common extents amounts to which exhausts all the possible unions of the minimal object sets discernible by the formal context. Note that each collects objects of the same property, see Table 2. One may then join and into a 3-tuple with common extent:

where , and .

Note that are introduced in order to differentiate the two intents. Clearly, the number of these 3-tuples equals the cardinality of set of common extent which counts . Moreover, manifests well-defined ordering. For , where and ,

iff and and .

Emergence of the GCL

Template:AnchorWhile it is generically impossible to determine subject to , the structure of concept hierarchy need not rely on these intents directly. An efficient way[4] to implement the concept hierarchy for is to consider intents in terms of single attributes.

Let henceforth and . Upon introducing , one may check that and , . Therefore,

,

which is a closed interval bounded from below by and from above by since . Moreover,

iff , iff iff .

In addition, , namely, the collection of intents exhausts all the generalised attributes , in comparison to . Then, the GCL enters as the lattice structure based on the formal context via :

- The collection of all the general concepts constitutes the poset ordered asTemplate:Anchor

iff and and .

- Both (meet) and (join) operations are applicable for finding further lattice points:

, where

, where

- The GCL appears to be a complete lattice since both and can be found in :

, .

Consequence of the general concept lattice

Manageable general lattice

The construction for FCL was known to count on efficient algorithms,[11][12] not to mention the construction for RSL which did not receive much attention yet. Intriguingly, though the GCL furnishes the general structure on which both the FCL and RSL can be rediscovered, the GCL can be acquired via simple readout.

Reading out the lattice

The completion of GCL[4] is equivalent to the completion of the intents of GCL in terms of the lower and bounds.

- The lower bounds can be employed to determine the upper bounds , and vice versa. For concreteness, both and are extents of the GCL, coexists with . Subsequently, and , where .

- The lower bounds of intents corresponding to minimal discernible object sets (s for ) can be employed to determine all the intents. Note that and appears to be a direct readout by means of .

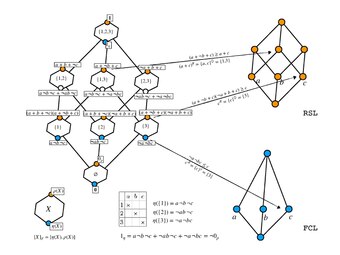

Template:AnchorThe above enables the determinations of the intents depicted as in Fig. 3 for the 3BS given by Table 1, where one can read out that , and . Hence, e.g., , . Note that the GCL also appears to be a Hasse diagram due to the resemblance of its extents to a power set. Moreover, each intent at also exhibits another Hasse diagram isomorphic to the ordering of attributes in the closed interval . It can be shown that where with . Hence, making the cardinality a constant given as . Clearly, one may check that

Rediscovering FCL and RSL on the GCL

The GCL underlies the original FCL and RSL subject to , as one can tell from and . To rediscover a node for FCL, one looks for a conjunction of attributes in contained in , which can be identified within the conjunctive normal form of if exists. Likewise, for the RSL one looks for a disjunction of attributes in contained in , which can be found within the disjunctive normal form of , see Fig 3.

For instance, from the node on the GCL, one finds that . Note that appears to be the only attribute belonging to , which is simultaneously a conjunction and a disjunction. Therefore, both the FCL and RSL have the concept in common. To illustrate a different situation, . Apparently, is the attribute emerging as disjunction of elements in which belongs to , in which no attribute composed by conjunction of elements in is found. Hence, could not be an extent of FCL, it only constitutes the concept for the RSL.

Information content of a formal context

Informative implications as equivalence due to categorisation

Non-tautological implication relations signify the information contained in the formal context and are referred to as informative implications.[6] In general, entails the implication . The implication is informative if it is (i.e. ).

In case it is strictly , one has where . Then, can be replaced by means of together with the tautology . Therefore, what remains to be taken into account is the equivalence for some . Logically, both attributes are properties carried by the same object class, reflects that equivalence relation.

All attributes in must be mutually implied,[4] which can be implemented, e.g., by (in fact, where is a tautology), i.e., all attributes are equivalent to the lower bound of intent.

A formula that implements all the informative implications

Extraction of the implications of type from the formal context was known to be complicated,[13][14][15][16][17] it necessitates efforts for constructing a canonical basis, which does not apply to the implications of type . By contrast, the above equivalence only proposes[4]

- the Template:Anchorsingle formula generating all the informative implications:

, which can be restated as ,

- Template:Anchoras an auxiliary formula,

is allowed by the formal context iff (or ).

Hence, purely algebraic formulae can be employed to determine the implication relations, one need not consult the object-attribute dependence in the formal context, which is the typical effort in finding the canonical basis. Template:Anchor

Remarkably, and are referred to as the contextual truth and falsity, respectively. and as well as and similar to the conventional truth 1 and falsity 0 that can be identified with and , respectively.

Beyond the set-to-set implications

and are found to be particular forms of . Assume and for both cases. By , an object set carrying all the attributes in implies carrying all the attributes in simultaneously, i.e. . By , an object set carrying any of the attributes in implies carrying some of the attributes in , therefore . Notably, the point of view conjunction-to-conjunction has also been emphasised by Ganter[5] while dealing with the attribute exploration.

One could overlook significant parts of the logic content in formal context were it not for the consideration based on the GCL. Here, the formal context describing 3BS given in Table 1 suggests an extreme case where no implication of the type could be found. Nevertheless, one ends up, e.g., (or ), whose meaning appears to be ambiguous. Though it is true that , one also notices that as well as . Indeed, by using the above formula with the provided in Fig. 2 it can be seen that , hence it is and that underlies .

Remarkably, the same formula will lead to (1) (or ) and (2) (or ), where , and can be interchanged. Hence, what one has captured from the 3BS are that (1) no two colours could coexist and that (2) there is no colour other than , and . The two issues are certainly less trivial in the scopes of and .

Rules to assemble or transform implications

The rules to assemble or transform implications of type are of direct consequences of object set inclusion relations. Notably, some of these rules can be reduced to the Armstrong axioms, which pertain to the main considerations of Guigues and Duquenne[6] based on the non-redundant collection of informative implications acquired via FCL. In particular,

(1) and since and leads to , i.e., .

In the case of , , and , where are sets of attributes, the rule (1) can be re-expressed as Armstrong's composition:

(1') and and .

The Armstrong axioms are not suited for which requires . This is in contrast to for which Armstrong's reflexivity is implemented by . Nevertheless, a similar composition may occur but signify a different rule from (1). Note that one also arrives at

(2) and since and , which gives rise to (2') and whenever , , and .

Example

For concreteness, consider the example depicted by Table 2, which has been originally adopted for clarification of the RSL[9] but worked out for the GCL.[4]

| Template:Diagonal split header | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||||

| 6 | |||||||||||

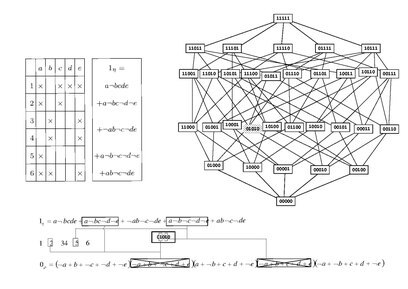

The GCL structure and the identifications of FCL and RSL on the GCL

- The determinations of the nodes of GCL for Table 2 are straightforward, as is depicted in Fig.4. For example, one may read out Template:Anchor

Fig. 4: Readout of GCL from a formal context. On each node, a binary string is to denote the extent, e.g., 01010 denotes the object set i.e. , 00100 denotes i.e. . In this figure, and are shown. Accordingly, one may identify all the lower and upper bounds of intents in the expressions the contextual truth and falsity ( and ), respectively.

, , , and so forth.

Clearly, one may also check that

.

- To rediscover the original FCL and RSL see Fig. 5. Observe, e.g.,

, .

Within the expression of

it can be seen that

, while within

it can be seen

. Therefore, one finds out the concepts

for FCL and

for RSL. By contrast,

,

with

gives rise to the concept

for FCL however fails to provide an extent for RSL because

Implication relations in general

- The meanings of and are essentially different.

and denote and , respectively.

For the present case, the above relations can be examined via the auxiliary formula:

(or ), (or ).

- and are equivalent when both are reduced to sets of single element.

Both and , according to the formal context of Table 2, are interpreted as , which means based on and based on .

Note that

. Moreover,

entails both

and

, which correspond to

and

, respectively.

- The single formula suffices to generate all the informative implications, where one may choose any attribute in as the antecedent or consequent.

(1) With one may infer the properties of objects of interest from the condition by specifying , thereby incorporating abundant informative implications as equivalent relations between any pair of attributes within the interval , i.e., if and . Note that entails since .

For instance, by

the relation

is neither of the type

nor of the type

. Nevertheless, one may also derive, e.g.,

,

and

, which are

,

and

, respectively. As a further interesting implication

entails

by means of material implication. Namely, for the objects carrying the property

or

,

must hold and, in addition, objects carrying the property

must also carry the property

and vice versa.

(1') Alternatively, the equivalent formula can be employed to specify the objects of particular interest. In effect, if and .

One may be interested in the properties inferring a particular consequent, say,

. Consider

giving rise to

according to Table 2. Clearly, with

one has

. This gives rise to many possible antecedents such as

,

,

,

and so forth.

(2) governs all the implications extractable from the formal context by means of (1) and (1'). Indeed, it plays the role of canonical basis with one single implication relation.

can be understood as or equivalently , which turns out be the only non-redundant implication one needs to deduce all the informative implications from any formal context. The basis or suffices the deduction of all implications as follows. While and , choosing either or gives rise to . Notably, this encompasses (1) and (1') by means of for any , where can be identified with some corresponding to one of the 32 nodes on the GCL in Fig. 4.

develops equivalence, at each single node, for all attributes contained within the interval . Moreover, informative implications could also relate different nodes via Hypothetical syllogism by invoking tautology. Typically, whenever . This corresponds to the cases considered in (1'): , , etc. Explicitly, is based upon and where . Note that and while (also ). Therefore, . Similarly, with gives .

Indeed,

or equivalently

plays the role of canonical basis with one single implication relation.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Template:Citation

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Template:Citation

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Template:Citation

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal