Real projective line

In geometry, a real projective line is a projective line over the real numbers. It is an extension of the usual concept of a line that has been historically introduced to solve a problem set by visual perspective: two parallel lines do not intersect but seem to intersect "at infinity". For solving this problem, points at infinity have been introduced, in such a way that in a real projective plane, two distinct projective lines meet in exactly one point. The set of these points at infinity, the "horizon" of the visual perspective in the plane, is a real projective line. It is the set of directions emanating from an observer situated at any point, with opposite directions identified.

An example of a real projective line is the projectively extended real line, which is often called the projective line.

Formally, a real projective line P(R) is defined as the set of all one-dimensional linear subspaces of a two-dimensional vector space over the reals. The automorphisms of a real projective line are called projective transformations, homographies, or linear fractional transformations. They form the projective linear group PGL(2, R). Each element of PGL(2, R) can be defined by a nonsingular 2×2 real matrix, and two matrices define the same element of PGL(2, R) if one is the product of the other and a nonzero real number.

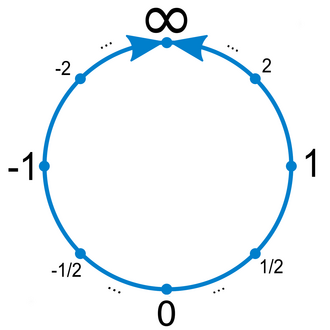

Topologically, real projective lines are homeomorphic to circles. The complex analog of a real projective line is a complex projective line, also called a Riemann sphere.

Definition

The points of the real projective line are usually defined as equivalence classes of an equivalence relation. The starting point is a real vector space of dimension 2, Template:Math. Define on Template:Math the binary relation Template:Math to hold when there exists a nonzero real number Template:Math such that Template:Math. The definition of a vector space implies almost immediately that this is an equivalence relation. The equivalence classes are the vector lines from which the zero vector has been removed. The real projective line Template:Math is the set of all equivalence classes. Each equivalence class is considered as a single point, or, in other words, a point is defined as being an equivalence class.

If one chooses a basis of Template:Math, this amounts (by identifying a vector with its coordinate vector) to identify Template:Math with the direct product Template:Math, and the equivalence relation becomes Template:Math if there exists a nonzero real number Template:Math such that Template:Math. In this case, the projective line Template:Math is preferably denoted Template:Math or . The equivalence class of the pair Template:Math is traditionally denoted Template:Math, the colon in the notation recalling that, if Template:Math, the ratio Template:Math is the same for all elements of the equivalence class. If a point Template:Math is the equivalence class Template:Math one says that Template:Math is a pair of projective coordinates of Template:Math.[1]

As Template:Math is defined through an equivalence relation, the canonical projection from Template:Math to Template:Math defines a topology (the quotient topology) and a differential structure on the projective line. However, the fact that equivalence classes are not finite induces some difficulties for defining the differential structure. These are solved by considering Template:Math as a Euclidean vector space. The circle of the unit vectors is, in the case of Template:Math, the set of the vectors whose coordinates satisfy Template:Math. This circle intersects each equivalence classes in exactly two opposite points. Therefore, the projective line may be considered as the quotient space of the circle by the equivalence relation such that Template:Math if and only if either Template:Math or Template:Math.

Charts

The projective line is a manifold. This can be seen by above construction through an equivalence relation, but is easier to understand by providing an atlas consisting of two charts

- Chart #1:

- Chart #2:

The equivalence relation provides that all representatives of an equivalence class are sent to the same real number by a chart.

Either of Template:Math or Template:Math may be zero, but not both, so both charts are needed to cover the projective line. The transition map between these two charts is the multiplicative inverse. As it is a differentiable function, and even an analytic function (outside of zero), the real projective line is both a differentiable manifold and an analytic manifold.

The inverse function of chart #1 is the map

It defines an embedding of the real line into the projective line, whose complement of the image is the point Template:Math. The pair consisting of this embedding and the projective line is called the projectively extended real line. Identifying the real line with its image by this embedding, one sees that the projective line may be considered as the union of the real line and the single point Template:Math, called the point at infinity of the projectively extended real line, and denoted Template:Math. This embedding allows us to identify the point Template:Math either with the real number Template:Math if Template:Math, or with Template:Math in the other case.

The same construction may be done with the other chart. In this case, the point at infinity is Template:Math. This shows that the notion of point at infinity is not intrinsic to the real projective line, but is relative to the choice of an embedding of the real line into the projective line.

Structure

Points of the real projective line can be associated with pairs of antipodal points on a circle. Generally, a projective n-space is formed from antipodal pairs on a sphere in (n+1)-space; in this case the sphere is a circle in the plane.

The real projective line is a complete projective range that is found in the real projective plane and in the complex projective line. Its structure is thus inherited from these superstructures. Primary among these structures is the relation of projective harmonic conjugates among the points of the projective range.

The real projective line has a cyclic order that extends the usual order of the real numbers.

Automorphisms

The projective linear group and its action

Matrix-vector multiplication defines a right action of Template:Math on the space Template:Math of row vectors: explicitly,

Since each matrix in Template:Math fixes the zero vector and maps proportional vectors to proportional vectors, there is an induced action of Template:Math on Template:Math: explicitly,[2]

(Here and below, the notation for homogeneous coordinates denotes the equivalence class of the row vector.

The elements of Template:Math that act trivially on Template:Math are the nonzero scalar multiples of the identity matrix; these form a subgroup denoted Template:Math. The projective linear group is defined to be the quotient group Template:Math. By the above, there is an induced faithful action of Template:Math on Template:Math. For this reason, the group Template:Math may also be called the group of linear automorphisms of Template:Math.

Linear fractional transformations

Using the identification Template:Math sending Template:Math to Template:Math and Template:Math to Template:Math, one obtains a corresponding action of Template:Math on Template:Math , which is by linear fractional transformations: explicitly, since

the class of in Template:Math acts as with the understanding that each fraction with denominator 0 should be interpreted as Template:Math.[3] and .[4]

Some authors use left action on column vectors which entails switching b and c in the matrix operator.[5][6][7]

Properties

- Given two ordered triples of distinct points in Template:Math, there exists a unique element of Template:Math mapping the first triple to the second; that is, the action is sharply 3-transitive. For example, the linear fractional transformation mapping Template:Math to Template:Math is the Cayley transform .

- The stabilizer in Template:Math of the point Template:Math is the affine group of the real line, consisting of the transformations for all Template:Math and Template:Math.

See also

Notes

References

- Juan Carlos Alvarez Paiva (2000) The Real Projective Line, course content from New York University.

- Santiago Cañez (2014) Notes on Projective Geometry from Northwestern University.

- ↑ The argument used to construct Template:Math can also be used with any field K and any dimension to construct the projective space Template:Math.

- ↑ Miyake, Modular forms, Springer, 2006, §1.1. This reference and some of the others below work with Template:Math instead of Template:Math, but the principle is the same.

- ↑ Koblitz, Introduction to elliptic curves and modular forms, Springer, 1993, III.§1.

- ↑ Lang, Complex analysis, Springer, 1999, VII, §5.

- ↑ Lang, Elliptic functions, Springer, 1987, 3.§1.

- ↑ Serre, A course in arithmetic, Springer, 1973, VII.1.1.

- ↑ Stillwell, Mathematics and its history, Springer, 2010, §8.6