Derivative of the exponential map

In the theory of Lie groups, the exponential map is a map from the Lie algebra Template:Math of a Lie group Template:Math into Template:Math. In case Template:Math is a matrix Lie group, the exponential map reduces to the matrix exponential. The exponential map, denoted Template:Math, is analytic and has as such a derivative Template:Math, where Template:Math is a Template:Math path in the Lie algebra, and a closely related differential Template:Math.[2]

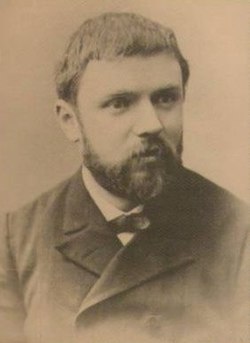

The formula for Template:Math was first proved by Friedrich Schur (1891).[3] It was later elaborated by Henri Poincaré (1899) in the context of the problem of expressing Lie group multiplication using Lie algebraic terms.[4] It is also sometimes known as Duhamel's formula.

The formula is important both in pure and applied mathematics. It enters into proofs of theorems such as the Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff formula, and it is used frequently in physics[5] for example in quantum field theory, as in the Magnus expansion in perturbation theory, and in lattice gauge theory.

Throughout, the notations Template:Math and Template:Math will be used interchangeably to denote the exponential given an argument, except when, where as noted, the notations have dedicated distinct meanings. The calculus-style notation is preferred here for better readability in equations. On the other hand, the Template:Math-style is sometimes more convenient for inline equations, and is necessary on the rare occasions when there is a real distinction to be made.

Statement

The derivative of the exponential map is given by[6]

- Explanation

To compute the differential Template:Math of Template:Math at Template:Math, Template:Math, the standard recipe[2]

is employed. With Template:Math the result[6] Template:NumBlk

follows immediately from Template:EquationNote. In particular, Template:Math is the identity because Template:Math (since Template:Math is a vector space) and Template:Math.

Proof

The proof given below assumes a matrix Lie group. This means that the exponential mapping from the Lie algebra to the matrix Lie group is given by the usual power series, i.e. matrix exponentiation. The conclusion of the proof still holds in the general case, provided each occurrence of Template:Math is correctly interpreted. See comments on the general case below.

The outline of proof makes use of the technique of differentiation with respect to Template:Math of the parametrized expression

to obtain a first order differential equation for Template:Math which can then be solved by direct integration in Template:Mvar. The solution is then Template:Math.

Lemma

Let Template:Math denote the adjoint action of the group on its Lie algebra. The action is given by Template:Math for Template:Math. A frequently useful relationship between Template:Math and Template:Math is given by[7][nb 1]

Proof

Using the product rule twice one finds,

Then one observes that

by Template:EquationNote above. Integration yields

Using the formal power series to expand the exponential, integrating term by term, and finally recognizing (Template:EquationNote),

and the result follows. The proof, as presented here, is essentially the one given in Template:Harvtxt. A proof with a more algebraic touch can be found in Template:Harvtxt.[8]

Comments on the general case

The formula in the general case is given by[9]

where[nb 2]

which formally reduces to

Here the Template:Math-notation is used for the exponential mapping of the Lie algebra and the calculus-style notation in the fraction indicates the usual formal series expansion. For more information and two full proofs in the general case, see the freely available Template:Harvtxt reference.

A direct formal argument

An immediate way to see what the answer must be, provided it exists is the following. Existence needs to be proved separately in each case. By direct differentiation of the standard limit definition of the exponential, and exchanging the order of differentiation and limit,

where each factor owes its place to the non-commutativity of Template:Math and Template:Math.

Dividing the unit interval into Template:Math sections Template:Math (Template:Math since the sum indices are integers) and letting Template:Mvar → ∞, Template:Math, Template:Math yields

Applications

Local behavior of the exponential map

The inverse function theorem together with the derivative of the exponential map provides information about the local behavior of Template:Math. Any Template:Math map Template:Math between vector spaces (here first considering matrix Lie groups) has a Template:Math inverse such that Template:Math is a Template:Math bijection in an open set around a point Template:Math in the domain provided Template:Math is invertible. From (Template:EquationNote) it follows that this will happen precisely when

is invertible. This, in turn, happens when the eigenvalues of this operator are all nonzero. The eigenvalues of Template:Math are related to those of Template:Math as follows. If Template:Math is an analytic function of a complex variable expressed in a power series such that Template:Math for a matrix Template:Math converges, then the eigenvalues of Template:Math will be Template:Math, where Template:Math are the eigenvalues of Template:Math, the double subscript is made clear below.[nb 3] In the present case with Template:Math and Template:Math, the eigenvalues of Template:Math are

where the Template:Math are the eigenvalues of Template:Math. Putting Template:Math one sees that Template:Math is invertible precisely when

The eigenvalues of Template:Math are, in turn, related to those of Template:Math. Let the eigenvalues of Template:Math be Template:Math. Fix an ordered basis Template:Math of the underlying vector space Template:Math such that Template:Math is lower triangular. Then

with the remaining terms multiples of Template:Math with Template:Math. Let Template:Math be the corresponding basis for matrix space, i.e. Template:Math. Order this basis such that Template:Math if Template:Math. One checks that the action of Template:Math is given by

with the remaining terms multiples of Template:Math. This means that Template:Math is lower triangular with its eigenvalues Template:Math on the diagonal. The conclusion is that Template:Math is invertible, hence Template:Math is a local bianalytical bijection around Template:Math, when the eigenvalues of Template:Math satisfy[10][nb 4]

In particular, in the case of matrix Lie groups, it follows, since Template:Math is invertible, by the inverse function theorem that Template:Math is a bi-analytic bijection in a neighborhood of Template:Math in matrix space. Furthermore, Template:Math, is a bi-analytic bijection from a neighborhood of Template:Math in Template:Math to a neighborhood of Template:Math.[11] The same conclusion holds for general Lie groups using the manifold version of the inverse function theorem.

It also follows from the implicit function theorem that Template:Math itself is invertible for Template:Math sufficiently small.[12]

Derivation of a Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff formula

Template:Main If Template:Math is defined such that

an expression for Template:Math, the Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff formula, can be derived from the above formula,

Its left-hand side is easy to see to equal Y. Thus,

However, using the relationship between Template:Math and Template:Math given by Template:EquationNote, it is straightforward to further see that

and hence

Putting this into the form of an integral in t from 0 to 1 yields,

an integral formula for Template:Math that is more tractable in practice than the explicit Dynkin's series formula due to the simplicity of the series expansion of Template:Math. Note this expression consists of Template:Math and nested commutators thereof with Template:Mvar or Template:Mvar. A textbook proof along these lines can be found in Template:Harvtxt and Template:Harvtxt.

Derivation of Dynkin's series formula

Dynkin's formula mentioned may also be derived analogously, starting from the parametric extension

whence

so that, using the above general formula,

Since, however,

the last step by virtue of the Mercator series expansion, it follows that Template:NumBlk and, thus, integrating,

It is at this point evident that the qualitative statement of the BCH formula holds, namely Template:Math lies in the Lie algebra generated by Template:Math and is expressible as a series in repeated brackets Template:EquationRef. For each Template:Mvar, terms for each partition thereof are organized inside the integral Template:Math. The resulting Dynkin's formula is then

For a similar proof with detailed series expansions, see Template:Harvtxt.

Combinatoric details

Change the summation index in (Template:EquationNote) to Template:Math and expand Template:NumBlk in a power series. To handle the series expansions simply, consider first Template:Math. The Template:Math-series and the Template:Math-series are given by

respectively. Combining these one obtains Template:NumBlk This becomes

where Template:Math is the set of all sequences Template:Math of length Template:Math subject to the conditions in Template:EquationNote.

Now substitute Template:Math for Template:Math in the LHS of (Template:EquationNote). Equation Template:EquationNote then gives

or, with a switch of notation, see An explicit Baker–Campbell–Hausdorff formula,

Note that the summation index for the rightmost Template:Math in the second term in (Template:EquationNote) is denoted Template:Math, but is not an element of a sequence Template:Math. Now integrate Template:Math, using Template:Math,

Write this as

This amounts to Template:NumBlk where using the simple observation that Template:Math for all Template:Math. That is, in (Template:EquationNote), the leading term vanishes unless Template:Math equals Template:Math or Template:Math, corresponding to the first and second terms in the equation before it. In case Template:Math, Template:Math must equal Template:Math, else the term vanishes for the same reason (Template:Math is not allowed). Finally, shift the index, Template:Math,

This is Dynkin's formula. The striking similarity with (99) is not accidental: It reflects the Dynkin–Specht–Wever map, underpinning the original, different, derivation of the formula.[15] Namely, if

is expressible as a bracket series, then necessarily[18] Template:NumBlk Putting observation Template:EquationNote and theorem (Template:EquationNote) together yields a concise proof of the explicit BCH formula.

See also

Remarks

Notes

References

- Template:Citation ; translation from Google books.

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Citation

- Veltman, M, 't Hooft, G & de Wit, B (2007). "Lie Groups in Physics", online lectures.

- Template:Cite journal

External links

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Template:Harvnb Appendix on analytic functions.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Template:Harvnb Theorem 5 Section 1.2

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Proposition 3.35

- ↑ See also Template:Harvnb from which Hall's proof is taken.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb This is equation (1.11).

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Proposition 7, section 1.2.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Corollary 3.44.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Section 1.6.

- ↑ Template:HarvnbSection 5.5.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Section 1.2.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Chapter 2.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Chapter 5.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb Chapter 1.12.2.

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "nb", but no corresponding <references group="nb"/> tag was found