Relationship between mathematics and physics

The relationship between mathematics and physics has been a subject of study of philosophers, mathematicians and physicists since antiquity, and more recently also by historians and educators.[2] Generally considered a relationship of great intimacy,[3] mathematics has been described as "an essential tool for physics"[4] and physics has been described as "a rich source of inspiration and insight in mathematics".[5] Some of the oldest and most discussed themes are about the main differences between the two subjects, their mutual influence, the role of mathematical rigor in physics, and the problem of explaining the effectiveness of mathematics in physics.

In his work Physics, one of the topics treated by Aristotle is about how the study carried out by mathematicians differs from that carried out by physicists.[6] Considerations about mathematics being the language of nature can be found in the ideas of the Pythagoreans: the convictions that "Numbers rule the world" and "All is number",[7][8] and two millennia later were also expressed by Galileo Galilei: "The book of nature is written in the language of mathematics".[9][10]

Historical interplay

Before giving a mathematical proof for the formula for the volume of a sphere, Archimedes used physical reasoning to discover the solution (imagining the balancing of bodies on a scale).[11] Aristotle classified physics and mathematics as theoretical sciences, in contrast to practical sciences (like ethics or politics) and to productive sciences (like medicine or botany).[12]

From the seventeenth century, many of the most important advances in mathematics appeared motivated by the study of physics, and this continued in the following centuries (although in the nineteenth century mathematics started to become increasingly independent from physics).[13][14] The creation and development of calculus were strongly linked to the needs of physics:[15] There was a need for a new mathematical language to deal with the new dynamics that had arisen from the work of scholars such as Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton.[16] The concept of derivative was needed, Newton did not have the modern concept of limits, and instead employed infinitesimals, which lacked a rigorous foundation at that time.[17] During this period there was little distinction between physics and mathematics;[18] as an example, Newton regarded geometry as a branch of mechanics.[19]

Non-Euclidean geometry, as formulated by Carl Friedrich Gauss, János Bolyai, Nikolai Lobachevsky, and Bernhard Riemann, freed physics from the limitation of a single Euclidean geometry.[20] A version of non-Euclidean geometry, called Riemannian geometry, enabled Einstein to develop general relativity by providing the key mathematical framework on which he fit his physical ideas of gravity.[21]

In the 19th century Auguste Comte in his hierarchy of the sciences, placed physics and astronomy as less general and more complex than mathematics, as both depend on it.[22] In 1900, David Hilbert in his 23 problems for the advancement of mathematical science, considered the axiomatization of physics as his sixth problem. The problem remains open.[23]

In 1930, Paul Dirac invented the Dirac delta function which produced a single value when used in an integral. The mathematical rigor of this function was in doubt until the mathematician Laurent Schwartz developed on the theory of distributions.[24]

Connections between the two fields sometimes only require identifing similar concepts by different names, as shown in the 1975 Wu–Yang dictionary,[25] that related concepts of gauge theory with differential geometry.[26]Template:Rp

Physics is not mathematics

Template:See also Despite the close relationship between math and physics, they are not synonyms. In mathematics objects can be defined exactly and logically related, but the object need have no relationship to experimental measurements. In physics, definitions are abstractions or idealizations, approximations adequate when compared to the natural world. In 1960, Georg Rasch noted that no models are ever true, not even Newton's laws, emphasizing that models should not be evaluated based on truth but on their applicability for a given purpose.[27] For example, Newton built a physical model around definitions like his second law of motion based on observations, leading to the development of calculus and highly accurate planetary mechanics, but later this definition was superseded by improved models of mechanics.[28] Mathematics deals with entities whose properties can be known with certainty.[29] According to David Hume, only statements that deal solely with ideas themselves—such as those encountered in mathematics—can be demonstrated to be true with certainty, while any conclusions pertaining to experiences of the real world can only be achieved via "probable reasoning".[30] This leads to a situation that was put by Albert Einstein as "No number of experiments can prove me right; a single experiment can prove me wrong."[31] The ultimate goal in research in pure mathematics are rigorous proofs, while in physics heuristic arguments may sometimes suffice in leading-edge research.[32] In short, the methods and goals of physicists and mathematicians are different.[33] Nonetheless, according to Roland Omnès, the axioms of mathematics are not mere conventions, but have physical origins.[34]

Role of rigor in physics

Template:See also Rigor is indispensable in pure mathematics.[35] But many definitions and arguments found in the physics literature involve concepts and ideas that are not up to the standards of rigor in mathematics.[32][36][37][38]

For example, Freeman Dyson characterized quantum field theory as having two "faces". The outward face looked at nature and there the predictions of quantum field theory are exceptionally successful. The inward face looked at mathematical foundations and found inconsistency and mystery. The success of the physical theory comes despite its lack of rigorous mathematical backing.[39]Template:Rp[40]Template:Rp

Philosophical problems

Some of the problems considered in the philosophy of mathematics are the following:

- Explain the effectiveness of mathematics in the study of the physical world: "At this point an enigma presents itself which in all ages has agitated inquiring minds. How can it be that mathematics, being after all a product of human thought which is independent of experience, is so admirably appropriate to the objects of reality?" —Albert Einstein, in Geometry and Experience (1921).[41]

- Clearly delineate mathematics and physics: For some results or discoveries, it is difficult to say to which area they belong: to the mathematics or to physics.[42]

- What is the geometry of physical space?[43]

- What is the origin of the axioms of mathematics?[44]

- How does the already existing mathematics influence in the creation and development of physical theories?[45]

- Is arithmetic analytic or synthetic? (from Kant, see Analytic–synthetic distinction)[46]

- What is essentially different between doing a physical experiment to see the result and making a mathematical calculation to see the result? (from the Turing–Wittgenstein debate)[47]

- Do Gödel's incompleteness theorems imply that physical theories will always be incomplete? (from Stephen Hawking)[48][49]

- Is mathematics invented or discovered? (millennia-old question, raised among others by Mario Livio)[50]

Education

In recent times the two disciplines have most often been taught separately, despite all the interrelations between physics and mathematics.[51] This led some professional mathematicians who were also interested in mathematics education, such as Felix Klein, Richard Courant, Vladimir Arnold and Morris Kline, to strongly advocate teaching mathematics in a way more closely related to the physical sciences.[52][53] The initial courses of mathematics for college students of physics are often taught by mathematicians, despite the differences in "ways of thinking" of physicists and mathematicians about those traditional courses and how they are used in the physics courses classes thereafter.[54]

See also

- Non-Euclidean geometry

- Fourier series

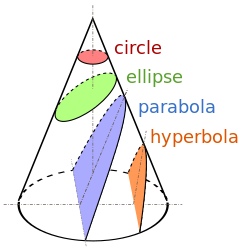

- Conic section

- Kepler's laws of planetary motion

- Saving the phenomena

- Template:Section link

- The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences

- Mathematical universe hypothesis

- Zeno's paradoxes

- Axiomatic system

- Mathematical model

- Empiricism

- Logicism

- Formalism

- Mathematics of general relativity

- Bourbaki

- Experimental mathematics

- History of Maxwell's equations

- Template:Section link

- History of astronomy

- Why Johnny Can't Add

- Mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics

- Scientific modelling

- All models are wrong

References

Further reading

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal (part 1) (part 2).

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite conference

- Template:Cite journal

External links

- Gregory W. Moore – Physical Mathematics and the Future (July 4, 2014)

- IOP Institute of Physics – Mathematical Physics: What is it and why do we need it? (September 2014)

- Feynman explaining the differences between mathematics and physics in a video available on YouTube

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite conference

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Kyle Forinash, William Rumsey, Chris Lang, Galileo's Mathematical Language of Nature Template:Webarchive.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ E. J. Post, A History of Physics as an Exercise in Philosophy, p. 76.

- ↑ Arkady Plotnitsky, Niels Bohr and Complementarity: An Introduction, p. 177.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Eoin P. O'Neill (editor), What Did You Do Today, Professor?: Fifteen Illuminating Responses from Trinity College Dublin, p. 62.

- ↑ Rédei, M. "On the Tension Between Physics and Mathematics". J Gen Philos Sci 51, pp. 411–425 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10838-019-09496-0

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite magazine

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Fundamentals of Physics - Volume 2 - Page 627, by David Halliday, Robert Resnick, Jearl Walker (1993)

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 MICHAEL ATIYAH ET AL. "RESPONSES TO THEORETICAL MATHEMATICS: TOWARD A CULTURAL SYNTHESIS OF MATHEMATICS AND THEORETICAL PHYSICS, BY A. JAFFE AND F. QUINN. https://www.ams.org/journals/bull/1994-30-02/S0273-0979-1994-00503-8/S0273-0979-1994-00503-8.pdf"

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Roland Omnès (2005) Converging Realities: Toward a Common Philosophy of Physics and Mathematics p. 38 and p. 215

- ↑ Steven Weinberg, To Explain the World: The Discovery of Modern Science, pp. 9–10.

- ↑ Kevin Davey. "Is Mathematical Rigor Necessary in Physics?", The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science, Vol. 54, No. 3 (Sep., 2003), pp. 439–463 https://www.jstor.org/stable/3541794

- ↑ Mark Steiner (1992), "Mathematical Rigor in Physics". https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203979105-13/mathematical-rigor-physics-mark-steiner

- ↑ P.W. Bridgman (1959), "How Much Rigor is Possible in Physics?" https://doi.org/10.1016/S0049-237X(09)70030-8

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Albert Einstein, Geometry and Experience.

- ↑ Pierre Bergé, Des rythmes au chaos.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Karam; Pospiech; & Pietrocola (2010). "Mathematics in physics lessons: developing structural skills"

- ↑ Stakhov "Dirac’s Principle of Mathematical Beauty, Mathematics of Harmony"

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ https://bridge.math.oregonstate.edu/papers/ampere.pdf