Supermassive black hole

Template:Short description Template:About Template:Use mdy dates

A supermassive black hole (SMBH or sometimes SBH)Template:Efn is the largest type of black hole, with its mass being on the order of hundreds of thousands, or millions to billions, of times the mass of the Sun (Template:Solar mass). Black holes are a class of astronomical objects that have undergone gravitational collapse, leaving behind spheroidal regions of space from which nothing can escape, including light. Observational evidence indicates that almost every large galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center.[5][6] For example, the Milky Way galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center, corresponding to the radio source Sagittarius A*.[7][8] Accretion of interstellar gas onto supermassive black holes is the process responsible for powering active galactic nuclei (AGNs) and quasars.[9]

Two supermassive black holes have been directly imaged by the Event Horizon Telescope: the black hole in the giant elliptical galaxy Messier 87 and the black hole at the Milky Way's center (Sagittarius A*).[10][11]

Description

Supermassive black holes are classically defined as black holes with a mass above 100,000 (Template:Val) solar masses (Template:Solar mass); some have masses of Template:Solar mass.[12] Supermassive black holes have physical properties that clearly distinguish them from lower-mass classifications. First, the tidal forces in the vicinity of the event horizon are significantly weaker for supermassive black holes. The tidal force on a body at a black hole's event horizon is inversely proportional to the square of the black hole's mass:[13] a person at the event horizon of a Template:Solar mass black hole experiences about the same tidal force between their head and feet as a person on the surface of the Earth. Unlike with stellar-mass black holes, one would not experience significant tidal force until very deep into the black hole's event horizon.[14]

It is somewhat counterintuitive to note that the average density of a SMBH within its event horizon (defined as the mass of the black hole divided by the volume of space within its Schwarzschild radius) can be smaller than the density of water.[15] This is because the Schwarzschild radius () is directly proportional to its mass. Since the volume of a spherical object (such as the event horizon of a non-rotating black hole) is directly proportional to the cube of the radius, the density of a black hole is inversely proportional to the square of the mass, and thus higher mass black holes have a lower average density.[16]

The Schwarzschild radius of the event horizon of a nonrotating and uncharged supermassive black hole of around Template:Solar mass is comparable to the semi-major axis of the orbit of planet Uranus, which is about 19 AU.[17][18]

Some astronomers refer to black holes of greater than Template:Solar mass as ultramassive black holes (UMBHs or UBHs),[19] but the term is not broadly used. Possible examples include the black holes at the cores of TON 618, NGC 6166, ESO 444-46 and NGC 4889,[20] which are among the most massive black holes known.

Some studies have suggested that the maximum natural mass that a black hole can reach, while being luminous accretors (featuring an accretion disk), is typically on the order of about Template:Solar mass.[21][22] However, a 2020 study suggested even larger black holes, dubbed stupendously large black holes (SLABs), with masses greater than Template:Solar mass, could exist based on used models; some studies place the black hole at the core of Phoenix A in this category.[23][24]

History of research

The story of how supermassive black holes were found began with the investigation by Maarten Schmidt of the radio source 3C 273 in 1963. Initially this was thought to be a star, but the spectrum proved puzzling. It was determined to be hydrogen emission lines that had been redshifted, indicating the object was moving away from the Earth.[25] Hubble's law showed that the object was located several billion light-years away, and thus must be emitting the energy equivalent of hundreds of galaxies. The rate of light variations of the source dubbed a quasi-stellar object, or quasar, suggested the emitting region had a diameter of one parsec or less. Four such sources had been identified by 1964.[26]

In 1963, Fred Hoyle and W. A. Fowler proposed the existence of hydrogen-burning supermassive stars (SMS) as an explanation for the compact dimensions and high energy output of quasars. These would have a mass of about Template:Nowrap. However, Richard Feynman noted stars above a certain critical mass are dynamically unstable and would collapse into a black hole, at least if they were non-rotating.[27] Fowler then proposed that these supermassive stars would undergo a series of collapse and explosion oscillations, thereby explaining the energy output pattern. Appenzeller and Fricke (1972) built models of this behavior, but found that the resulting star would still undergo collapse, concluding that a non-rotating Template:Val SMS "cannot escape collapse to a black hole by burning its hydrogen through the CNO cycle".[28]

Edwin E. Salpeter and Yakov Zeldovich made the proposal in 1964 that matter falling onto a massive compact object would explain the properties of quasars. It would require a mass of around Template:Val to match the output of these objects. Donald Lynden-Bell noted in 1969 that the infalling gas would form a flat disk that spirals into the central "Schwarzschild throat". He noted that the relatively low output of nearby galactic cores implied these were old, inactive quasars.[29] Meanwhile, in 1967, Martin Ryle and Malcolm Longair suggested that nearly all sources of extra-galactic radio emission could be explained by a model in which particles are ejected from galaxies at relativistic velocities, meaning they are moving near the speed of light.[30] Martin Ryle, Malcolm Longair, and Peter Scheuer then proposed in 1973 that the compact central nucleus could be the original energy source for these relativistic jets.[29]

Arthur M. Wolfe and Geoffrey Burbidge noted in 1970 that the large velocity dispersion of the stars in the nuclear region of elliptical galaxies could only be explained by a large mass concentration at the nucleus; larger than could be explained by ordinary stars. They showed that the behavior could be explained by a massive black hole with up to Template:Val, or a large number of smaller black holes with masses below Template:Val.[31] Dynamical evidence for a massive dark object was found at the core of the active elliptical galaxy Messier 87 in 1978, initially estimated at Template:Val.[32] Discovery of similar behavior in other galaxies soon followed, including the Andromeda Galaxy in 1984 and the Sombrero Galaxy in 1988.[5]

Donald Lynden-Bell and Martin Rees hypothesized in 1971 that the center of the Milky Way galaxy would contain a massive black hole.[33] Sagittarius A* was discovered and named on February 13 and 15, 1974, by astronomers Bruce Balick and Robert Brown using the Green Bank Interferometer of the National Radio Astronomy Observatory.[34] They discovered a radio source that emits synchrotron radiation; it was found to be dense and immobile because of its gravitation. This was, therefore, the first indication that a supermassive black hole exists in the center of the Milky Way.

The Hubble Space Telescope, launched in 1990, provided the resolution needed to perform more refined observations of galactic nuclei. In 1994 the Faint Object Spectrograph on the Hubble was used to observe Messier 87, finding that ionized gas was orbiting the central part of the nucleus at a velocity of ±500 km/s. The data indicated a concentrated mass of Template:Val lay within a Template:Val span, providing strong evidence of a supermassive black hole.[35]

Using the Very Long Baseline Array to observe Messier 106, Miyoshi et al. (1995) were able to demonstrate that the emission from an H2O maser in this galaxy came from a gaseous disk in the nucleus that orbited a concentrated mass of Template:Val, which was constrained to a radius of 0.13 parsecs. Their ground-breaking research noted that a swarm of solar mass black holes within a radius this small would not survive for long without undergoing collisions, making a supermassive black hole the sole viable candidate.[36] Accompanying this observation which provided the first confirmation of supermassive black holes was the discovery[37] of the highly broadened, ionised iron Kα emission line (6.4 keV) from the galaxy MCG-6-30-15. The broadening was due to the gravitational redshift of the light as it escaped from just 3 to 10 Schwarzschild radii from the black hole.

On April 10, 2019, the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration released the first horizon-scale image of a black hole, in the center of the galaxy Messier 87.[2] In March 2020, astronomers suggested that additional subrings should form the photon ring, proposing a way of better detecting these signatures in the first black hole image.[38][39]

Formation

The origin of supermassive black holes remains an active field of research. Astrophysicists agree that black holes can grow by accretion of matter and by merging with other black holes.[40][41] There are several hypotheses for the formation mechanisms and initial masses of the progenitors, or "seeds", of supermassive black holes. Independently of the specific formation channel for the black hole seed, given sufficient mass nearby, it could accrete to become an intermediate-mass black hole and possibly a SMBH if the accretion rate persists.[42]

Distant and early supermassive black holes, such as J0313–1806,[43] and ULAS J1342+0928,[44] are hard to explain so soon after the Big Bang. Some postulate they might come from direct collapse of dark matter with self-interaction.[45][46][47] A small minority of sources argue that they may be evidence that the Universe is the result of a Big Bounce, instead of a Big Bang, with these supermassive black holes being formed before the Big Bounce.[48][49]

First stars

Template:Main Template:Update The early progenitor seeds may be black holes of Template:Solar mass that are left behind by the explosions of massive stars and grow by accretion of matter. Another model involves a dense stellar cluster undergoing core collapse as the negative heat capacity of the system drives the velocity dispersion in the core to relativistic speeds.[50][51]

Before the first stars, large gas clouds could collapse into a "quasi-star", which would in turn collapse into a black hole of around Template:Solar mass.[42] These stars may have also been formed by dark matter halos drawing in enormous amounts of gas by gravity, which would then produce supermassive stars with Template:Solar mass.[52][53] The "quasi-star" becomes unstable to radial perturbations because of electron-positron pair production in its core and could collapse directly into a black hole without a supernova explosion (which would eject most of its mass, preventing the black hole from growing as fast).

A more recent theory proposes that SMBH seeds were formed in the very early universe each from the collapse of a supermassive star with mass of around Template:Solar mass.[54]

Direct-collapse and primordial black holes

Large, high-redshift clouds of metal-free gas,[55] when irradiated by a sufficiently intense flux of Lyman–Werner photons,[56] can avoid cooling and fragmenting, thus collapsing as a single object due to self-gravitation.[57][58] The core of the collapsing object reaches extremely large values of matter density, of the order of about Template:Val, and triggers a general relativistic instability.[59] Thus, the object collapses directly into a black hole, without passing from the intermediate phase of a star, or of a quasi-star. These objects have a typical mass of about Template:Solar mass and are named direct collapse black holes.[60]

A 2022 computer simulation showed that the first supermassive black holes can arise in rare turbulent clumps of gas, called primordial halos, that were fed by unusually strong streams of cold gas. The key simulation result was that cold flows suppressed star formation in the turbulent halo until the halo's gravity was finally able to overcome the turbulence and formed two direct-collapse black holes of Template:Solar mass and Template:Solar mass. The birth of the first SMBHs can therefore be a result of standard cosmological structure formation.[61][62]

Primordial black holes (PBHs) could have been produced directly from external pressure in the first moments after the Big Bang. These black holes would then have more time than any of the above models to accrete, allowing them sufficient time to reach supermassive sizes. Formation of black holes from the deaths of the first stars has been extensively studied and corroborated by observations. The other models for black hole formation listed above are theoretical.

The formation of a supermassive black hole requires a relatively small volume of highly dense matter having small angular momentum. Normally, the process of accretion involves transporting a large initial endowment of angular momentum outwards, and this appears to be the limiting factor in black hole growth. This is a major component of the theory of accretion disks. Gas accretion is both the most efficient and the most conspicuous way in which black holes grow. The majority of the mass growth of supermassive black holes is thought to occur through episodes of rapid gas accretion, which are observable as active galactic nuclei or quasars.

Observations reveal that quasars were much more frequent when the Universe was younger, indicating that supermassive black holes formed and grew early. A major constraining factor for theories of supermassive black hole formation is the observation of distant luminous quasars, which indicate that supermassive black holes of Template:Solar mass had already formed when the Universe was less than one billion years old. This suggests that supermassive black holes arose very early in the Universe, inside the first massive galaxies.Template:Citation needed

Maximum mass limit

There is a natural upper limit to how large supermassive black holes can grow. Supermassive black holes in any quasar or active galactic nucleus (AGN) appear to have a theoretical upper limit of physically around Template:Solar mass for typical parameters, as anything above this slows growth down to a crawl (the slowdown tends to start around Template:Solar mass) and causes the unstable accretion disk surrounding the black hole to coalesce into stars that orbit it.[21][64][65][66] A study concluded that the radius of the innermost stable circular orbit (ISCO) for SMBH masses above this limit exceeds the self-gravity radius, making disc formation no longer possible.[21]

A larger upper limit of around Template:Solar mass was represented as the absolute maximum mass limit for an accreting SMBH in extreme cases, for example its maximal prograde spin with a dimensionless spin parameter of a = 1,[24][21] although the maximum limit for a black hole's spin parameter is very slightly lower at a = 0.9982.[67] At masses just below the limit, the disc luminosity of a field galaxy is likely to be below the Eddington limit and not strong enough to trigger the feedback underlying the M–sigma relation, so SMBHs close to the limit can evolve above this.[24]

It was noted that, black holes close to this limit are likely to be rather even rarer, as it would require the accretion disc to be almost permanently prograde because the black hole grows and the spin-down effect of retrograde accretion is larger than the spin-up by prograde accretion, due to its ISCO and therefore its lever arm.[21] This would require the hole spin to be permanently correlated with a fixed direction of the potential controlling gas flow, within the black hole's host galaxy, and thus would tend to produce a spin axis and hence AGN jet direction, which is similarly aligned with the galaxy. Current observations do not support this correlation.[21]

The so-called 'chaotic accretion' presumably has to involve multiple small-scale events, essentially random in time and orientation if it is not controlled by a large-scale potential in this way.[21] This would lead the accretion statistically to spin-down, due to retrograde events having larger lever arms than prograde, and occurring almost as often.[21] There is also other interactions with large SMBHs that trend to reduce their spin, including particularly mergers with other black holes, which can statistically decrease the spin.[21] All of these considerations suggested that SMBHs usually cross the critical theoretical mass limit at modest values of their spin parameters, so that Template:Val in all but rare cases.[21]

Although modern UMBHs within quasars and galactic nuclei cannot grow beyond around Template:Val through the accretion disk and as well given the current age of the universe, some of these monster black holes in the universe are predicted to still continue to grow up to stupendously large masses of perhaps Template:Val during the collapse of superclusters of galaxies in the extremely far future of the universe.[68]

Activity and galactic evolution

Gravitation from supermassive black holes in the center of many galaxies is thought to power active objects such as Seyfert galaxies and quasars, and the relationship between the mass of the central black hole and the mass of the host galaxy depends upon the galaxy type.[69][70] An empirical correlation between the size of supermassive black holes and the stellar velocity dispersion of a galaxy bulge[71] is called the M–sigma relation.

An AGN is now considered to be a galactic core hosting a massive black hole that is accreting matter and displays a sufficiently strong luminosity. The nuclear region of the Milky Way, for example, lacks sufficient luminosity to satisfy this condition. The unified model of AGN is the concept that the large range of observed properties of the AGN taxonomy can be explained using just a small number of physical parameters. For the initial model, these values consisted of the angle of the accretion disk's torus to the line of sight and the luminosity of the source. AGN can be divided into two main groups: a radiative mode AGN in which most of the output is in the form of electromagnetic radiation through an optically thick accretion disk, and a jet mode in which relativistic jets emerge perpendicular to the disk.[72]

Mergers and recoiled SMBHs

Template:Main The interaction of a pair of SMBH-hosting galaxies can lead to merger events. Dynamical friction on the hosted SMBH objects causes them to sink toward the center of the merged mass, eventually forming a pair with a separation of under a kiloparsec. The interaction of this pair with surrounding stars and gas will then gradually bring the SMBH together as a gravitationally bound binary system with a separation of ten parsecs or less. Once the pair draw as close as 0.001 parsecs, gravitational radiation will cause them to merge. By the time this happens, the resulting galaxy will have long since relaxed from the merger event, with the initial starburst activity and AGN having faded away.[73]

The gravitational waves from this coalescence can give the resulting SMBH a velocity boost of up to several thousand km/s, propelling it away from the galactic center and possibly even ejecting it from the galaxy. This phenomenon is called a gravitational recoil.[74] The other possible way to eject a black hole is the classical slingshot scenario, also called slingshot recoil. In this scenario first a long-lived binary black hole forms through a merger of two galaxies. A third SMBH is introduced in a second merger and sinks into the center of the galaxy. Due to the three-body interaction one of the SMBHs, usually the lightest, is ejected. Due to conservation of linear momentum the other two SMBHs are propelled in the opposite direction as a binary. All SMBHs can be ejected in this scenario.[75] An ejected black hole is called a runaway black hole.[76]

There are different ways to detect recoiling black holes. Often a displacement of a quasar/AGN from the center of a galaxy[77] or a spectroscopic binary nature of a quasar/AGN is seen as evidence for a recoiled black hole.[78]

Candidate recoiling black holes include NGC 3718,[79] SDSS1133,[80] 3C 186,[81] E1821+643[82] and SDSSJ0927+2943.[78] Candidate runaway black holes are HE0450–2958,[77] CID-42[83] and objects around RCP 28.[84] Runaway supermassive black holes may trigger star formation in their wakes.[76] A linear feature near the dwarf galaxy RCP 28 was interpreted as the star-forming wake of a candidate runaway black hole.[84][85][86]

Hawking radiation

Template:Main Hawking radiation is black-body radiation that is predicted to be released by black holes, due to quantum effects near the event horizon. This radiation reduces the mass and energy of black holes, causing them to shrink and ultimately vanish. If black holes evaporate via Hawking radiation, a non-rotating and uncharged stupendously large black hole with a mass of Template:Val will evaporate in around Template:Val.[87][18] Black holes formed during the predicted collapse of superclusters of galaxies in the far future with Template:Val would evaporate over a timescale of up to Template:Val.[68][18]

Evidence

Doppler measurements

Some of the best evidence for the presence of black holes is provided by the Doppler effect whereby light from nearby orbiting matter is red-shifted when receding and blue-shifted when advancing. For matter very close to a black hole the orbital speed must be comparable with the speed of light, so receding matter will appear very faint compared with advancing matter, which means that systems with intrinsically symmetric discs and rings will acquire a highly asymmetric visual appearance. This effect has been allowed for in modern computer-generated images such as the example presented here, based on a plausible model[88] for the supermassive black hole in Sgr A* at the center of the Milky Way. However, the resolution provided by presently available telescope technology is still insufficient to confirm such predictions directly.

What already has been observed directly in many systems are the lower non-relativistic velocities of matter orbiting further out from what are presumed to be black holes. Direct Doppler measures of water masers surrounding the nuclei of nearby galaxies have revealed a very fast Keplerian motion, only possible with a high concentration of matter in the center. Currently, the only known objects that can pack enough matter in such a small space are black holes, or things that will evolve into black holes within astrophysically short timescales. For active galaxies farther away, the width of broad spectral lines can be used to probe the gas orbiting near the event horizon. The technique of reverberation mapping uses variability of these lines to measure the mass and perhaps the spin of the black hole that powers active galaxies.

In the Milky Way

Evidence indicates that the Milky Way galaxy has a supermassive black hole at its center, 26,000 light-years from the Solar System, in a region called Sagittarius A*[90] because:

- The star S2 follows an elliptical orbit with a period of 15.2 years and a pericenter (closest distance) of 17 light-hours (Template:Val or 120 AU) from the center of the central object.[91]

- From the motion of star S2, the object's mass can be estimated as Template:Solar mass,[92] or about Template:Val.

- The radius of the central object must be less than 17 light-hours, because otherwise S2 would collide with it. Observations of the star S14[93] indicate that the radius is no more than 6.25 light-hours, about the diameter of Uranus' orbit.

- No known astronomical object other than a black hole can contain Template:Solar mass in this volume of space.[93]

Infrared observations of bright flare activity near Sagittarius A* show orbital motion of plasma with a period of Template:Val at a separation of six to ten times the gravitational radius of the candidate SMBH. This emission is consistent with a circularized orbit of a polarized "hot spot" on an accretion disk in a strong magnetic field. The radiating matter is orbiting at 30% of the speed of light just outside the innermost stable circular orbit.[94]

On January 5, 2015, NASA reported observing an X-ray flare 400 times brighter than usual, a record-breaker, from Sagittarius A*. The unusual event may have been caused by the breaking apart of an asteroid falling into the black hole or by the entanglement of magnetic field lines within gas flowing into Sagittarius A*, according to astronomers.[95]

Outside the Milky Way

Unambiguous dynamical evidence for supermassive black holes exists only for a handful of galaxies;[97] these include the Milky Way, the Local Group galaxies M31 and M32, and a few galaxies beyond the Local Group, such as NGC 4395. In these galaxies, the root mean square (or rms) velocities of the stars or gas rises proportionally to 1/Template:Var near the center, indicating a central point mass. In all other galaxies observed to date, the rms velocities are flat, or even falling, toward the center, making it impossible to state with certainty that a supermassive black hole is present.[97]

Nevertheless, it is commonly accepted that the center of nearly every galaxy contains a supermassive black hole.[98] The reason for this assumption is the M–sigma relation, a tight (low scatter) relation between the mass of the hole in the 10 or so galaxies with secure detections, and the velocity dispersion of the stars in the bulges of those galaxies.[99] This correlation, although based on just a handful of galaxies, suggests to many astronomers a strong connection between the formation of the black hole and the galaxy itself.[98]

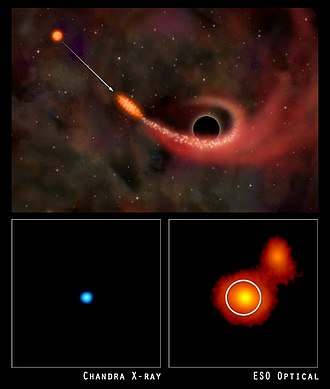

On March 28, 2011, a supermassive black hole was seen tearing a mid-size star apart.[100] That is the only likely explanation of the observations that day of sudden X-ray radiation and the follow-up broad-band observations.[101][102] The source was previously an inactive galactic nucleus, and from study of the outburst the galactic nucleus is estimated to be a SMBH with mass of the order of a Template:Solar mass. This rare event is assumed to be a relativistic outflow (material being emitted in a jet at a significant fraction of the speed of light) from a star tidally disrupted by the SMBH. A significant fraction of a solar mass of material is expected to have accreted onto the SMBH. Subsequent long-term observation will allow this assumption to be confirmed if the emission from the jet decays at the expected rate for mass accretion onto a SMBH.

Individual studies

The nearby Andromeda Galaxy, 2.5 million light-years away, contains a Template:Solar mass central black hole, significantly larger than the Milky Way's.[103] The largest supermassive black hole in the Milky Way's vicinity appears to be that of Messier 87 (i.e., M87*), at a mass of Template:Nowrap at a distance of 48.92 million light-years.[104] The supergiant elliptical galaxy NGC 4889, at a distance of 336 million light-years away in the Coma Berenices constellation, contains a black hole measured to be Template:Solar mass.[105]

Masses of black holes in quasars can be estimated via indirect methods that are subject to substantial uncertainty. The quasar TON 618 is an example of an object with an extremely large black hole, estimated at Template:Solar mass.[106] Its redshift is 2.219. Other examples of quasars with large estimated black hole masses are the hyperluminous quasar APM 08279+5255, with an estimated mass of Template:Solar mass,[107] and the quasar SMSS J215728.21-360215.1, with a mass of Template:Solar mass, or nearly 10,000 times the mass of the black hole at the Milky Way's Galactic Center.[108]

Some galaxies, such as the galaxy 4C +37.11, appear to have two supermassive black holes at their centers, forming a binary system. If they collided, the event would create strong gravitational waves.[109] Binary supermassive black holes are believed to be a common consequence of galactic mergers.[110] The binary pair in OJ 287, 3.5 billion light-years away, contains the most massive black hole in a pair, with a mass estimated at Template:Solar mass.[111][112] In 2011, a super-massive black hole was discovered in the dwarf galaxy Henize 2-10, which has no bulge. The precise implications for this discovery on black hole formation are unknown, but may indicate that black holes formed before bulges.[113]

File:A Black Hole’s Dinner is Fast Approaching - Part 2.ogv

In 2012, astronomers reported an unusually large mass of approximately Template:Solar mass for the black hole in the compact, lenticular galaxy NGC 1277, which lies 220 million light-years away in the constellation Perseus. The putative black hole has approximately 59 percent of the mass of the bulge of this lenticular galaxy (14 percent of the total stellar mass of the galaxy).[114] Another study reached a very different conclusion: this black hole is not particularly overmassive, estimated at between Template:Solar mass with Template:Solar mass being the most likely value.[115] On February 28, 2013, astronomers reported on the use of the NuSTAR satellite to accurately measure the spin of a supermassive black hole for the first time, in NGC 1365, reporting that the event horizon was spinning at almost the speed of light.[116][117]

In September 2014, data from different X-ray telescopes have shown that the extremely small, dense, ultracompact dwarf galaxy M60-UCD1 hosts a 20 million solar mass black hole at its center, accounting for more than 10% of the total mass of the galaxy. The discovery is quite surprising, since the black hole is five times more massive than the Milky Way's black hole despite the galaxy being less than five-thousandths the mass of the Milky Way.

Some galaxies lack any supermassive black holes in their centers. Although most galaxies with no supermassive black holes are very small, dwarf galaxies, one discovery remains mysterious: The supergiant elliptical cD galaxy A2261-BCG has not been found to contain an active supermassive black hole of at least Template:Val, despite the galaxy being one of the largest galaxies known; over six times the size and one thousand times the mass of the Milky Way. Despite that, several studies gave very large mass values for a possible central black hole inside A2261-BGC, such as about as large as Template:Val or as low as Template:Val. Since a supermassive black hole will only be visible while it is accreting, a supermassive black hole can be nearly invisible, except in its effects on stellar orbits. This implies that either A2261-BGC has a central black hole that is accreting at a low level or has a mass rather below Template:Val.[118]

In December 2017, astronomers reported the detection of the most distant quasar known by this time, ULAS J1342+0928, containing the most distant supermassive black hole, at a reported redshift of z = 7.54, surpassing the redshift of 7 for the previously known most distant quasar ULAS J1120+0641.[119][120][121] Template:Multiple image

From: Chandra X-ray Observatory

In February 2020, astronomers reported the discovery of the Ophiuchus Supercluster eruption, the most energetic event in the Universe ever detected since the Big Bang.[122][123][124] It occurred in the Ophiuchus Cluster in the galaxy NeVe 1, caused by the accretion of nearly Template:Solar mass of material by its central 7 billion Template:Solar mass supermassive black hole.[125] The eruption lasted for about 100 million years and released 5.7 million times more energy than the most powerful gamma-ray burst known. The eruption released shock waves and jets of high-energy particles that punched the intracluster medium, creating a cavity about 1.5 million light-years wide – ten times the Milky Way's diameter.[126][122][127][128]

In February 2021, astronomers released, for the first time, a very high-resolution image of 25,000 active supermassive black holes, covering four percent of the Northern celestial hemisphere, based on ultra-low radio wavelengths, as detected by the Low-Frequency Array (LOFAR) in Europe.[129]

See also

Notes

References

Further reading

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

- Template:Cite journal

External links

Template:Spoken Wikipedia Template:Wikinews category

- Black Holes: Gravity's Relentless Pull Interactive multimedia Web site about the physics and astronomy of black holes from the Space Telescope Science Institute

- Images of supermassive black holes

- NASA images of supermassive black holes

- The black hole at the heart of the Milky Way

- ESO video clip of stars orbiting a galactic black hole

- Star Orbiting Massive Milky Way Centre Approaches to within 17 Light-Hours ESO, October 21, 2002

- Images, Animations, and New Results from the UCLA Galactic Center Group

- Washington Post article on Supermassive black holes

- Video (2:46) – Simulation of stars orbiting Milky Way's central massive black hole

- Video (2:13) – Simulation reveals supermassive black holes (NASA, October 2, 2018)

- From Super to Ultra: Just How Big Can Black Holes Get? Template:Webarchive

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

- Template:Cite web

Template:Black holes Template:Milky Way Template:Portal bar

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Citation. t = 8min

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedcarr - ↑ Template:Cite conference

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal. See in particular equation (27).

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 Template:Cite news

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite news