Envelope (waves)

Template:Short description In physics and engineering, the envelope of an oscillating signal is a smooth curve outlining its extremes.[1] The envelope thus generalizes the concept of a constant amplitude into an instantaneous amplitude. The figure illustrates a modulated sine wave varying between an upper envelope and a lower envelope. The envelope function may be a function of time, space, angle, or indeed of any variable.

In beating waves

A common situation resulting in an envelope function in both space x and time t is the superposition of two waves of almost the same wavelength and frequency:[2]

which uses the trigonometric formula for the addition of two sine waves, and the approximation Δλ ≪ λ:

Here the modulation wavelength λmod is given by:[2][3]

The modulation wavelength is double that of the envelope itself because each half-wavelength of the modulating cosine wave governs both positive and negative values of the modulated sine wave. Likewise the beat frequency is that of the envelope, twice that of the modulating wave, or 2Δf.[4]

If this wave is a sound wave, the ear hears the frequency associated with f and the amplitude of this sound varies with the beat frequency.[4]

Phase and group velocity

The argument of the sinusoids above apart from a factor 2Template:Pi are:

with subscripts C and E referring to the carrier and the envelope. The same amplitude F of the wave results from the same values of ξC and ξE, each of which may itself return to the same value over different but properly related choices of x and t. This invariance means that one can trace these waveforms in space to find the speed of a position of fixed amplitude as it propagates in time; for the argument of the carrier wave to stay the same, the condition is:

which shows to keep a constant amplitude the distance Δx is related to the time interval Δt by the so-called phase velocity vp

On the other hand, the same considerations show the envelope propagates at the so-called group velocity vg:[5]

A more common expression for the group velocity is obtained by introducing the wavevector k:

We notice that for small changes Δλ, the magnitude of the corresponding small change in wavevector, say Δk, is:

so the group velocity can be rewritten as:

where ω is the frequency in radians/s: ω = 2Template:Pif. In all media, frequency and wavevector are related by a dispersion relation, ω = ω(k), and the group velocity can be written:

In a medium such as classical vacuum the dispersion relation for electromagnetic waves is:

where c0 is the speed of light in classical vacuum. For this case, the phase and group velocities both are c0.

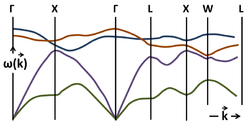

In so-called dispersive media the dispersion relation can be a complicated function of wavevector, and the phase and group velocities are not the same. For example, for several types of waves exhibited by atomic vibrations (phonons) in GaAs, the dispersion relations are shown in the figure for various directions of wavevector k. In the general case, the phase and group velocities may have different directions.[7]

In function approximation

In condensed matter physics an energy eigenfunction for a mobile charge carrier in a crystal can be expressed as a Bloch wave:

where n is the index for the band (for example, conduction or valence band) r is a spatial location, and k is a wavevector. The exponential is a sinusoidally varying function corresponding to a slowly varying envelope modulating the rapidly varying part of the wavefunction un,k describing the behavior of the wavefunction close to the cores of the atoms of the lattice. The envelope is restricted to k-values within a range limited by the Brillouin zone of the crystal, and that limits how rapidly it can vary with location r.

In determining the behavior of the carriers using quantum mechanics, the envelope approximation usually is used in which the Schrödinger equation is simplified to refer only to the behavior of the envelope, and boundary conditions are applied to the envelope function directly, rather than to the complete wavefunction.[9] For example, the wavefunction of a carrier trapped near an impurity is governed by an envelope function F that governs a superposition of Bloch functions:

where the Fourier components of the envelope F(k) are found from the approximate Schrödinger equation.[10] In some applications, the periodic part uk is replaced by its value near the band edge, say k=k0, and then:[9]

In diffraction patterns

Diffraction patterns from multiple slits have envelopes determined by the single slit diffraction pattern. For a single slit the pattern is given by:[11]

where α is the diffraction angle, d is the slit width, and λ is the wavelength. For multiple slits, the pattern is [11]

where q is the number of slits, and g is the grating constant. The first factor, the single-slit result I1, modulates the more rapidly varying second factor that depends upon the number of slits and their spacing.

Estimation

An envelope detector is a circuit that attempts to extract the envelope from an analog signal.

In digital signal processing, the envelope may be estimated employing the Hilbert transform or a moving RMS amplitude.[12]

See also

- Template:Slink

- Empirical mode decomposition

- Envelope (mathematics)

- Envelope tracking

- Instantaneous phase

- Modulation

- Mathematics of oscillation

- Peak envelope power

- Spectral envelope

References

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedJohnson - ↑ 2.0 2.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTipler - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedEberly - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCardona - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCerveny - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBastard - ↑ 9.0 9.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSchuller - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedimpurity - ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHarris - ↑ Template:Cite web