Projective harmonic conjugate

Template:Mvar form a harmonic range.

Template:Mvar is a complete quadrangle generating it.

In projective geometry, the harmonic conjugate point of a point on the real projective line with respect to two other points is defined by the following construction:

- Given three collinear points Template:Mvar, let Template:Mvar be a point not lying on their join and let any line through Template:Mvar meet Template:Mvar at Template:Mvar respectively. If Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar meet at Template:Mvar, and Template:Mvar meets Template:Mvar at Template:Mvar, then Template:Mvar is called the harmonic conjugate of Template:Mvar with respect to Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar.[1]

The point Template:Mvar does not depend on what point Template:Mvar is taken initially, nor upon what line through Template:Mvar is used to find Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar. This fact follows from Desargues theorem.

In real projective geometry, harmonic conjugacy can also be defined in terms of the cross-ratio as Template:Math.

Cross-ratio criterion

The four points are sometimes called a harmonic range (on the real projective line) as it is found that Template:Mvar always divides the segment Template:Overline internally in the same proportion as Template:Mvar divides Template:Overline externally. That is:

If these segments are now endowed with the ordinary metric interpretation of real numbers they will be signed and form a double proportion known as the cross ratio (sometimes double ratio)

for which a harmonic range is characterized by a value of −1. We therefore write:

The value of a cross ratio in general is not unique, as it depends on the order of selection of segments (and there are six such selections possible). But for a harmonic range in particular there are just three values of cross ratio: Template:Math since −1 is self-inverse – so exchanging the last two points merely reciprocates each of these values but produces no new value, and is known classically as the harmonic cross-ratio.

In terms of a double ratio, given points Template:Mvar on an affine line, the division ratio[2] of a point Template:Mvar is Note that when Template:Math, then Template:Math is negative, and that it is positive outside of the interval. The cross-ratio is a ratio of division ratios, or a double ratio. Setting the double ratio to minus one means that when Template:Math, then Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar are harmonic conjugates with respect to Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar. So the division ratio criterion is that they be additive inverses.

Harmonic division of a line segment is a special case of Apollonius' definition of the circle.

In some school studies the configuration of a harmonic range is called harmonic division.

Of midpoint

When Template:Mvar is the midpoint of the segment from Template:Mvar to Template:Mvar, then By the cross-ratio criterion, the harmonic conjugate of Template:Mvar will be Template:Mvar when Template:Math. But there is no finite solution for Template:Mvar on the line through Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar. Nevertheless, thus motivating inclusion of a point at infinity in the projective line. This point at infinity serves as the harmonic conjugate of the midpoint Template:Mvar.

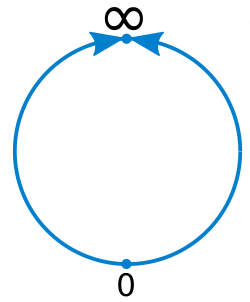

From complete quadrangle

Another approach to the harmonic conjugate is through the concept of a complete quadrangle such as Template:Mvar in the above diagram. Based on four points, the complete quadrangle has pairs of opposite sides and diagonals. In the expression of harmonic conjugates by H. S. M. Coxeter, the diagonals are considered a pair of opposite sides:

- Template:Mvar is the harmonic conjugate of Template:Mvar with respect to Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar, which means that there is a quadrangle Template:Mvar such that one pair of opposite sides intersect at Template:Mvar, and a second pair at Template:Mvar, while the third pair meet Template:Mvar at Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar.[3]

It was Karl von Staudt that first used the harmonic conjugate as the basis for projective geometry independent of metric considerations:

- ...Staudt succeeded in freeing projective geometry from elementary geometry. In his Template:Lang, Staudt introduced a harmonic quadruple of elements independently of the concept of the cross ratio following a purely projective route, using a complete quadrangle or quadrilateral.[4]

(ignore green M).

To see the complete quadrangle applied to obtaining the midpoint, consider the following passage from J. W. Young:

- If two arbitrary lines Template:Mvar are drawn through Template:Mvar and lines Template:Mvar are drawn through Template:Mvar parallel to Template:Mvar respectively, the lines Template:Mvar meet, by definition, in a point Template:Mvar at infinity, while Template:Mvar meet by definition in a point Template:Mvar at infinity. The complete quadrilateral Template:Mvar then has two diagonal points at Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar, while the remaining pair of opposite sides pass through Template:Mvar and the point at infinity on Template:Mvar. The point Template:Mvar is then by construction the harmonic conjugate of the point at infinity on Template:Mvar with respect to Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar. On the other hand, that Template:Mvar is the midpoint of the segment Template:Mvar follows from the familiar proposition that the diagonals of a parallelogram (Template:Mvar) bisect each other.[5]

Quaternary relations

Four ordered points on a projective range are called harmonic points when there is a tetrastigm in the plane such that the first and third are codots and the other two points are on the connectors of the third codot.[6]

If Template:Mvar is a point not on a straight with harmonic points, the joins of Template:Mvar with the points are harmonic straights. Similarly, if the axis of a pencil of planes is skew to a straight with harmonic points, the planes on the points are harmonic planes.[6]

A set of four in such a relation has been called a harmonic quadruple.[7]

Projective conics

A conic in the projective plane is a curve Template:Mvar that has the following property: If Template:Mvar is a point not on Template:Mvar, and if a variable line through Template:Mvar meets Template:Mvar at points Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar, then the variable harmonic conjugate of Template:Mvar with respect to Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar traces out a line. The point Template:Mvar is called the pole of that line of harmonic conjugates, and this line is called the polar line of Template:Mvar with respect to the conic. See the article Pole and polar for more details.

Inversive geometry

Template:Main In the case where the conic is a circle, on the extended diameters of the circle, harmonic conjugates with respect to the circle are inverses in a circle. This fact follows from one of Smogorzhevsky's theorems:[8]

- If circles Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar are mutually orthogonal, then a straight line passing through the center of Template:Mvar and intersecting Template:Mvar, does so at points symmetrical with respect to Template:Mvar.

That is, if the line is an extended diameter of Template:Mvar, then the intersections with Template:Mvar are harmonic conjugates.

Conics and Joachimthal's equation

Consider as the curve an ellipse given by the equation

Let be a point outside the ellipse and a straight line from which meets the ellipse at points and . Let have coordinates . Next take a point on and inside the ellipse which is such that divides the line segment in the ratio to , i.e.

- .

Instead of solving these equations for and it is easier to verify by substitution that the following expressions are the solutions, i.e.

Since the point lies on the ellipse , one has

or

This equation - which is a quadratic in - is called Joachimthal's equation. Its two roots , determine the positions of and in relation to and . Let us associate with and with . Then the various line segments are given by

and

It follows that

When this expression is , we have

Thus divides ``internally´´ in the same proportion as divides ``externally´´. The expression

with value (which makes it self-inverse) is known as the harmonic cross ratio. With as above, one has and hence the coefficient of in Joachimthal's equation vanishes, i.e.

This is the equation of a straight line called the polar (line) of point (pole) . One can show that this polar of is the chord of contact of the tangents to the ellipse from . If we put on the ellipse () the equation is that of the tangent at . One can also sho that the directrix of the ellipse is the polar of the focus.

Galois tetrads

In Galois geometry over a Galois field Template:Math a line has Template:Math points, where Template:Math. In this line four points form a harmonic tetrad when two harmonically separate the others. The condition

characterizes harmonic tetrads. Attention to these tetrads led Jean Dieudonné to his delineation of some accidental isomorphisms of the projective linear groups Template:Math for Template:Math.[9]

If Template:Math, and given Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar, then the harmonic conjugate of Template:Mvar is itself.[10]

Iterated projective harmonic conjugates and the golden ratio

Let Template:Math be three different points on the real projective line. Consider the infinite sequence of points Template:Mvar, where Template:Mvar is the harmonic conjugate of Template:Math with respect to Template:Math for Template:Math. This sequence is convergent.[11]

For a finite limit Template:Mvar we have

where is the golden ratio, i.e. for large Template:Mvar. For an infinite limit we have

For a proof consider the projective isomorphism

with

References

- Juan Carlos Alverez (2000) Projective Geometry, see Chapter 2: The Real Projective Plane, section 3: Harmonic quadruples and von Staudt's theorem.

- Robert Lachlan (1893) An Elementary Treatise on Modern Pure Geometry, link from Cornell University Historical Math Monographs.

- Bertrand Russell (1903) Principles of Mathematics, page 384.

- Template:Cite book

- ↑ R. L. Goodstein & E. J. F. Primrose (1953) Axiomatic Projective Geometry, University College Leicester (publisher). This text follows synthetic geometry. Harmonic construction on page 11

- ↑ Dirk Struik (1953) Lectures on Analytic and Projective Geometry, page 7

- ↑ H. S. M. Coxeter (1942) Non-Euclidean Geometry, page 29, University of Toronto Press

- ↑ B.L. Laptev & B.A. Rozenfel'd (1996) Mathematics of the 19th Century: Geometry, page 41, Birkhäuser Verlag Template:Isbn

- ↑ John Wesley Young (1930) Projective Geometry, page 85, Mathematical Association of America, Chicago: Open Court Publishing

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 G. B. Halsted (1906) Synthetic Projective Geometry, pages 15 & 16

- ↑ Luis Santaló (1966) Geometría proyectiva, page 166, Editorial Universitaria de Buenos Aires

- ↑ A.S. Smogorzhevsky (1982) Lobachevskian Geometry, Mir Publishers, Moscow

- ↑ Jean Dieudonné (1954) "Les Isomorphisms exceptionnals entre les groups classiques finis", Canadian Journal of Mathematics 6: 305 to 15 Template:Doi

- ↑ Emil Artin (1957) Geometric Algebra, page 82 via Internet Archive

- ↑ F. Leitenberger (2016) Iterated harmonic divisions and the golden ratio, Forum Geometricorum 16: 429–430