Equality (mathematics)

Template:Short description Template:About Template:Use dmy dates Template:CS1 config

In mathematics, equality is a relationship between two quantities or expressions, stating that they have the same value, or represent the same mathematical object.[1][2] Equality between Template:Math and Template:Math is written Template:Math, and pronounced "Template:Math equals Template:Math". In this equality, Template:Math and Template:Math are distinguished by calling them left-hand side (LHS), and right-hand side (RHS).[3] Two objects that are not equal are said to be distinct.[4]

Equality is often considered a kind of primitive notion, meaning, it is not formally defined, but rather informally said to be "a relation each thing bears to itself and nothing else". This characterization is notably circular ("nothing else"). This makes equality a somewhat slippery idea to pin down.

Basic properties about equality like reflexivity, symmetry, and transitivity have been understood intuitively since at least the ancient Greeks, but weren't symbolically stated as general properties of relations until the late 19th century by Giuseppe Peano. Other properties like substitution and function application weren't formally stated until the development of symbolic logic.

There are generally two ways that equality is formalized in mathematics: through logic or through set theory. In logic, equality is a primitive predicate (a statement that may have free variables) with the reflexive property (called the Law of identity), and the substitution property. From those, one can derive the rest of the properties usually needed for equality. Logic also defines the principle of extensionality, which defines two objects of a certain kind to be equal if they satisfy the same external property (See the example of sets below).

After the foundational crisis in mathematics at the turn of the 20th century, set theory (specifically Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory) became the most common foundation of mathematics in order to resolve the crisis. In set theory, any two sets are defined to be equal if they have all the same members. This is called the Axiom of extensionality. Usually set theory is defined within logic, and therefore uses the equality described above, however, if a logic system does not have equality, it is possible to define equality within set theory.

Etymology

In English, the word equal is derived from the Latin Template:Lang ('like', 'comparable', 'similar'), which itself stems from Template:Lang ('level', 'just').[6] The word entered Middle English around the 14th century, borrowed from Old French Template:Lang (modern Template:Lang).[7] More generally, the interlingual synonyms of equal have been used more broadly throughout history (see Template:Section link).

Before the 16th century, there was no common symbol for equality, and equality was usually expressed with a word, such as aequales, aequantur, esgale, faciunt, ghelijck, or gleich, and sometimes by the abbreviated form aeq, or simply Template:Angbr and Template:Angbr.[8] Diophantus's use of Template:Angbr, short for Template:Lang (Template:Tlit 'equals'), in Arithmetica (Template:Circa) is considered one of the first uses of an equals sign.[9]

The sign Template:Char, now universally accepted in mathematics for equality, was first recorded by Welsh mathematician Robert Recorde in The Whetstone of Witte (1557). The original form of the symbol was much wider than the present form. In his book, Recorde explains his design of the "Gemowe lines", from the Latin Template:Lang ('twin'), using two parallel lines to represent equality because he believed that "no two things could be more equal."[10]

Recorde's symbol was not immediately popular. After its introduction, it wasn't used again in print until 1618 (61 years later), in an anonymous Appendix in Edward Wright's English translation of Descriptio, by John Napier. It wasn't until 1631 that it received more than general recognition in England, being adopted as the symbol for equality in a few influential works. Later used by several influential mathematicians, most notably, both Isaac Newton and Gottfried Leibnitz, and due to the prevalence of calculus at the time, it quickly spread throughout the rest of Europe.[11]

Basic properties

- Reflexivity

-

- For every Template:Mvar, one has Template:Math.

- Symmetry

-

- For every Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar, if Template:Math, then Template:Math.

- Transitivity

-

- For every Template:Mvar, Template:Mvar, and Template:Mvar, if Template:Math and Template:Math, then Template:Math.[12][13]

- Substitution

-

- Informally, this just means that if Template:Math, then Template:Mvar can replace Template:Mvar in any mathematical expression or formula without changing its meaning. (For a formal explanation, see Template:Section link) For example:Template:Blist

- Operation application

-

- For every Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar, with some operation , if Template:Math, then .[14]Template:Efn For example:Template:Blist

The first three properties are generally attributed to Giuseppe Peano for being the first to explicitly state these as fundamental properties of equality in his Template:Lang (1889).[15][16] However, the basic notions have always existed; for example, in Euclid's Elements (Template:Circa), he includes 'common notions': "Things that are equal to the same thing are also equal to one another" (transitivity), "Things that coincide with one another are equal to one another" (reflexivity), along with some operation-application properties for addition and subtraction.[17] The operation-application property was also stated in Peano's Template:Lang,[15] however, it had been common practice in algebra since at least Diophantus (Template:Circa).[18] The substitution property is generally attributed to Gottfried Leibniz (Template:Circa).

Equations

An equation is a symbolic equality of two mathematical expressions connected with an equals sign (=). Algebra is the branch of mathematics concerned with equation solving: the problem of finding values of some variable, called Template:Em, for which the specified equality is true. Each value of the unknown for which the equation holds is called a Template:Em of the given equation; also stated as Template:Em the equation. For example, the equation has the values and as its only solutions. The terminology is used similarly for equations with several unknowns.[19] The set of solutions to an equation or system of equations is called its solution set.[20] For example, the set of all solution pairs of the equation forms the unit circle in analytic geometry; therefore, this equation is called Template:Em.[21]

In mathematical logic and computer science, an equation may described as a binary formula or Boolean-valued expression, which may be true for some values of the variables (if any) and false for other values.[22] More specifically, an equation represents a binary relation (i.e., a two-argument predicate) which may produce a truth value (true or false) from its arguments. In computer programming, the computation from the two expressions is known as comparison.[23]

Identities

An identity is an equality that is true for all values of its variables in a given domain.[24][25] An "equation" may sometimes mean an identity, but more often than not, it Template:Em a subset of the variable space to be the subset where the equation is true. An example is , which is true for each real number . There is no standard notation that distinguishes an equation from an identity, or other use of the equality relation: one has to guess an appropriate interpretation from the semantics of expressions and the context.[26] Sometimes, but not always, an identity is written with a triple bar: [27] This notation was introduced by Bernhard Riemann in his 1857 Elliptische Funktionen lectures (published in 1899).[28][29][30]

Alternatively, identities may be viewed as an equality of functions, where instead of writing , one may simply write .[31] This is called the extensionality of functions.[32] Viewed like this, the operation-application property still applies, but here, the operations are operators on a function space (a function acting on functions) like composition and the derivative, or functionals like function evaluation or the integral.

Definitions

Equations are often used to introduce new terms or symbols for constants, assert equalities, and introduce shorthand for complex expressions, which is called "equal by definition", and often denoted with ().[33] It is similar to the concept of assignment of a variable in computer science. For example, defines Euler's number,[34] and is the defining property of the imaginary number .

In mathematical logic, this is called an extension by definition (by equality) which is a conservative extension to a formal system.Template:Sfn This is done by taking the equation defining the new constant symbol as a new axiom of the theory.

The first recorded symbolic use of "Equal by definition" appeared in Logica Matematica (1894) by Cesare Burali-Forti, an Italian mathematician. Burali-Forti, in his book, used the notation ().[35][36]

In logic

History

Equality (or identity) is often considered a primitive notion, informally said to be "a relation each thing bears to itself and to no other thing".[37] This tradition can be traced back to at least 350 BC by Aristotle: in his Categories, he defines the notion of quantity in terms of a more primitive equality (distinct from identity or similarity), stating:[38]

"The most distinctive mark of quantity is that equality and inequality are predicated of it. Each of the aforesaid quantities is said to be equal or unequal. For instance, one solid is said to be equal or unequal to another; number, too, and time can have these terms applied to them, indeed can all those kinds of quantity that have been mentioned. Template:BrThat which is not a quantity can by no means, it would seem, be termed equal or unequal to anything else. One particular disposition or one particular quality, such as whiteness, is by no means compared with another in terms of equality and inequality but rather in terms of similarity. Thus it is the distinctive mark of quantity that it can be called equal and unequal." ― (Translated by E. M. Edghill)

Aristotle had separate categories for quantities (number, length, volume) and qualities (temperature, density, pressure), now called intensive and extensive properties. The Scholastics, particularly Richard Swineshead and other Oxford Calculators in the 14th century, began seriously thinking about kinematics and quantitative treatment of qualities, a major development in the quantification of physics, and which broadened the scope of mathematical objects beyond numbers and magnitudes.[39][40]

Around the 19th century, with the growth of modern logic, it became necessary to have a more concrete description of equality. With the rise of predicate logic due to the work of Gottlob Frege, logic shifted from being focused on classes of objects to being property-based. This was followed by a movement for describing mathematics in logical foundations, called logicism. This trend lead to the axiomatization of equality through the law of identity and the substitution property especially in mathematical logic[12][41] and analytic philosophy.[42]

The precursor to the substitution property of equality was first formulated by Gottfried Leibniz in his Discourse on Metaphysics (1686), stating, roughly, that "No two distinct things can have all properties in common." This has since broken into two principles, the substitution property (if , then any property of is a property of ), and its converse, the identity of indiscernibles (if and have all properties in common, then ).[43] Its introduction to logic, and first symbolic formulation is due to Bertrand Russell and Alfred Whitehead in their Principia Mathematica (1910), who claim it follows from their axiom of reducibility, but credit Leibniz for the idea.[44]

Axioms

Law of identity: Stating that each thing is identical with itself, without restriction. That is, for every

,

. It is the first of the traditional three laws of thought. Stated symbolically as:

Substitution property: Sometimes referred to as Leibniz's law,[45] generally states that if two things are equal, then any property of one must be a property of the other. It can be stated formally as: for every Template:Mvar and Template:Mvar, and any formula

(with a free variable Template:Mvar), if

, then

. Stated symbolically as:

Function application is also sometimes included in the axioms of equality,[14] but isn't necessary as it can be deduced from the other two axioms, and similarly for symmetry and transitivity. (See Template:Section link)

In first-order logic, these are axiom schemas (usually, see below), each of which specify an infinite set of axioms. If a theory has a predicate that satisfies the Law of Identity and Substitution property, it is common to say that it "has equality," or is "a theory with equality."Template:Sfn The use of "equality" here is a misnomer in that an arbitrary binary predicate that satisfies those properties may not be true equality, and there is no property or list of properties one could add to correct for this.[46][47] If, however, one is given that a predicate is true equality, then those properties are enough, since if has all the same properties as , and has the property of being equal to , then has the property of being equal to .[44][48]

As axioms, one can deduce from the first using universal instantiation, and the from second, given and , by using modus ponens twice. Alternatively, each of these may be included in logic as rules of inference.[49] The first called "equality introduction", and the second "equality elimination"[50] (also called paramodulation), used by some theoretical computer scientists like John Alan Robinson in their work on resolution and automated theorem proving.[51]

Objections

As mentioned above, these axioms don't explicitly define equality, in the sense that we still don't know if two objects are equal, only that if they're equal, then they have the same properties. If these axioms were to define a complete axiomatization of equality, meaning, if they were to define equality, then the converse of the second statement must be true. This is because any reflexive relation satisfying the substitution property within a given theory would be considered an "equality" for that theory. The converse of the Substitution property is the identity of indiscernibles, which states that two distinct things cannot have all their properties in common. Stated symbolically as:[43]

In mathematics, the identity of indiscernibles is usually rejected since indiscernibles in mathematical logic are not necessarily forbidden. Outside of pure math, the identity of indiscernibles has attracted much controversy and criticism, especially from corpuscular philosophy and quantum mechanics.[52]Template:Efn

Derivations of basic properties

- Reflexivity of Equality: Given some set Template:Math with a relation Template:Math induced by equality (), assume . Then by the Law of identity, thus .

- Symmetry of Equality: Given some set Template:Math with a relation Template:Math induced by equality (), assume there are elements such that . Then, take the formula . So we have . Since by assumption, and by Reflexivity, we have that .

- Transitivity of Equality: Given some set Template:Math with a relation Template:Math induced by equality (), assume there are elements such that and . Then take the formula . So we have . Since by symmetry, and by assumption, we have that .

- Function application: Given some function , assume there are elements Template:Math and Template:Math from its domain such that Template:Math, then take the formula . So we have

Since by assumption, and by reflexivity, we have that .

In set theory

Template:MainTemplate:Multiple image Set theory is the branch of mathematics that studies sets, which can be informally described as "collections of objects."[53] Although objects of any kind can be collected into a set, set theory – as a branch of mathematics – is mostly concerned with those that are relevant to mathematics as a whole. Sets are uniquely characterized by their elements; this means that two sets that have precisely the same elements are equal (they are the same set).[54] In a formalized set theory, this is usually defined by an axiom called the Axiom of extensionality.[55]

For example, using set builder notation,

Which states that "The set of all integers greater than 0 but not more than 3 is equal to the set containing only 1, 2, and 3", despite the differences in notation.

José Ferreirós credits Richard Dedekind for being the first to explicitly state the principle, (although he does not assert it as a definition):

"It very frequently happens that different things a, b, c ... considered for any reason under a common point of view, are collected together in the mind, and one then says that they form a system S; one calls the things a, b, c ... the elements of the system S, they are contained in S; conversely, S consists of these elements. Such a system S (or a collection, a manifold, a totality), as an object of our thought, is likewise a thing; it is completely determined when, for every thing, it is determined whether it is an element of S or not." ― Richard Dedekind, 1888 (Translated by José Ferreirós)

Background

Around the turn of the 20th century, mathematics faced several paradoxes and counter-intuitive results. For example, Russell's paradox showed a contradiction of naive set theory, it was shown that the parallel postulate cannot be proved, the existence of mathematical objects that cannot be computed or explicitly described, and the existence of theorems of arithmetic that cannot be proved with Peano arithmetic. The result was a foundational crisis of mathematics.[57]

The resolution of this crisis involved the rise of a new mathematical discipline called mathematical logic, which studies formal logic within mathematics. Subsequent discoveries in the 20th century then stabilized the foundations of mathematics into a coherent framework valid for all mathematics. This framework is based on a systematic use of axiomatic method and on set theory, specifically Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory, developed by Ernst Zermelo and Abraham Fraenkel. This set theory (and set theory in general) is now considered the most common foundation of mathematics.[58]

Extensionality

The term extensionality, as used in 'Axiom of Extensionality' has its roots in logic. An intensional definition describes the necessary and sufficient conditions for a term to apply to an object. For example: "An even number is an integer which is divisible by 2." An extensional definition instead lists all objects where the term applies. For example: "An even number is any one of the following integers: 0, 2, 4, 6, 8..., -2, -4, -8..." In logic, the extension of a predicate is the set of all things for which the predicate is true.[59]

The logical term was introduced to set theory in 1893, Gottlob Frege attempted to use this idea of an extension formally in his Foundations of Arithmetic, where, if is a predicate, its extension , is the set of all objects satisfying .[60] For example if is "x is even" then is the set . In his work, he defined his infamous Basic Law V as:Stating that if two predicates have the same extensions (they are satisfied by the same set of objects) then they are logically equivalent, however, it was determined later that this axiom led to Russell's paradox. The first explicit statement of the modern Axiom of Extensionality was in 1908 by Ernst Zermelo in a paper on the well-ordering theorem, where he presented the first axiomatic set theory, now called Zermelo set theory, which became the basis of modern set theories.[61] The specific term for "Extensionality" used by Zermelo was "Bestimmtheit".The specific English term "extensionality" only became common in mathematical and logical texts in the 1920s and 1930s,[62] particularly with the formalization of logic and set theory by figures like Alfred Tarski and John von Neumann.

Set equality based on first-order logic with equality

In first-order logic with equality (See Template:Section link), the axiom of extensionality states that two sets that contain the same elements are the same set.[63]

- Logic axiom:

- Logic axiom:

- Set theory axiom:

The first two are given by the substitution property of equality from first-order logic; the last is a new axiom of the theory. Incorporating half of the work into the first-order logic may be regarded as a mere matter of convenience, as noted by Azriel Lévy.

- "The reason why we take up first-order predicate calculus with equality is a matter of convenience; by this, we save the labor of defining equality and proving all its properties; this burden is now assumed by the logic."[64]

Set equality based on first-order logic without equality

In first-order logic without equality, two sets are defined to be equal if they contain the same elements. Then the axiom of extensionality states that two equal sets are contained in the same sets.[65]

- Set theory definition:

- Set theory axiom:

Or, equivalently, one may choose to define equality in a way that mimics, the substitution property explicitly, as the conjunction of all atomic formuals:[66]

- Set theory definition:

- Set theory axiom:

In either case, the Axiom of Extensionality based on first-order logic without equality states:

Proof of basic properties

- Reflexivity: Given a set , assume , it follows trivially that , and the same follows in reverse, therefore , thus .

- Symmetry: Given sets , such that , then , which implies , thus .

- Transitivity: Given sets , such that (1) and (2) , assume , then by (1), which implies by (2), and similarly for the reverse, therefore , thus .

- Function application: Given and , then . It can be proven that , using Kuratowski's definition: Template:Efn Then, since by the Axiom of Extensionality, they must belong to the same sets, so, since we have or Thus

Similar relations

Approximate equality

Numerical approximation is the study of algorithms that use numerical approximation (as opposed to symbolic manipulations) for the problems of mathematical analysis.

Calculations are likely to involve rounding errors and other approximation errors. Log tables, slide rules, and calculators produce approximate answers to all but the simplest calculations. The results of computer calculations are normally an approximation, expressed in a limited number of significant digits, although they can be programmed to produce more precise results.[67]

If viewed as a binary relation, (denoted by the symbol ) between real numbers or other things, if precisely defined, is not an equivalence relation since it's not transitive, even if modeled as a fuzzy relation.[68]

In computer science, equality is given by some relational operator. Real numbers are often approximated by floating-point numbers (A sequence of some fixed number of digits of a given base, scaled by an integer exponent of that base), thus it is common to store an expression that denotes the real number as to not lose precision. However, the equality of two real numbers given by an expression is known to be undecidable (specifically, real numbers defined by expressions involving the integers, the basic arithmetic operations, the logarithm and the exponential function). In other words, there cannot exist any algorithm for deciding such an equality (see Richardson's theorem).

A questionable equality under test may be denoted using the symbol.[69]

Equivalence relation

An equivalence relation is a mathematical relation that generalizes the idea of similarity or sameness. It is defined on a set as a binary relation that satisfies the three properties: reflexivity, symmetry, and transitivity. Reflexivity means that every element in is equivalent to itself ( for all ). Symmetry requires that if one element is equivalent to another, the reverse also holds (). Transitivity ensures that if one element is equivalent to a second, and the second to a third, then the first is equivalent to the third ( and ). These properties are enough to partition a set into disjoint equivalence classes. Conversely, every partition defines an equivalence class.

The equivalence relation of equality is a special case, as, if restricted to a given set , it is the strictest possible equivalence relation on ; specifically, equality partitions a set into equivalence classes consisting of all singleton sets. Other equivalence relations, while less restrictive, often generalize equality by identifying elements based on shared properties or transformations, such as congruence in modular arithmetic or similarity in geometry.

Congruence relation

Template:Main In abstract algebra, a congruence relation extends the idea of an equivalence relation to include the operation-application property. That is, given a set , and a set of operations on , then a congruence relation has the property that for all operations (here, written as unary to avoid cumbersome notation, but may be of any arity). A congruence relation on an algebraic structure such as a group, ring, or module is an equivalence relation that respects the operations defined on that structure.[70]

Isomorphism

In mathematics, especially in abstract algebra and category theory, it is common to deal with objects that already have some internal structure. An isomorphism describes a kind of structure-preserving correspondence between two objects, establishing them as essentially identical in their structure or properties.

More formally, an isomorphism is a bijective mapping (or morphism) between two sets or structures and such that and its inverse preserve the operations, relations, or functions defined on those structures.[71] This means that any operation or relation valid in corresponds precisely to the operation or relation in under the mapping. For example, in group theory, a group isomorphism satisfies for all elements , where denotes the group operation.

When two objects or systems are isomorphic, they are considered indistinguishable in terms of their internal structure, even though their elements or representations may differ. For instance, all cyclic groups of order are isomorphic to the integers, , with addition.[72] Similarly, in linear algebra, two vector spaces are isomorphic if they have the same dimension, as there exists a linear bijection between their elements.[73]

The concept of isomorphism extends to numerous branches of mathematics, including graph theory (graph isomorphism), topology (homeomorphism), and algebra (group and ring isomorpisms), among others. Isomorphisms facilitate the classification of mathematical entities and enable the transfer of results and techniques between similar systems. Bridging the gap between isomorphism and equality was one motivation for the development of category theory, as well as for homotopy type theory and univalent foundations.[74][75][76]

Geometry

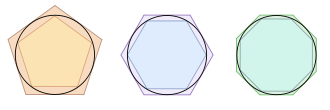

In geometry, formally, two figures are equal if they contain exactly the same points. However, historically, geometric-equality has always been taken to be much broader. Euclid and Archimedes used "equal" (ἴσος isos) often referring to figures with the same area or those that could be cut and rearranged to form one another. For example, Euclid stated the Pythagorean theorem as “the square on the hypotenuse is equal to the squares on the sides, taken together”; and Archimedes said that “a circle is equal to the rectangle whose sides are the radius and half the circumference.”[77]

This notion persisted until Adrien-Marie Legendre, who introduced the term "equivalent" to describe figures of equal area and restricted "equal" to what we now call “congruent”—the same shape and size, or if one has the same shape and size as the mirror image of the other.[78][79] Euclid's terminology continued in the work of David Hilbert in his Grundlagen der Geometrie, who further refined Euclid's ideas by introducing the notions of polygons being "divisibly equal" (zerlegungsgleich) if they can be cut into finitely many triangles which are congruent, and "equal in content" (inhaltsgleichheit) if one can add finitely many divisibly equal polygons to each such that the resulting polygons are divisibly equal.[80]

After the rise of set theory, around the 1960s, there was a push for a reform in mathematics education called New Math, following Andrey Kolmogorov, who, in an effort to restructure Russian geometry courses, proposed presenting geometry through the lens of transformations and set theory. Since a figure was seen as a set of points, it could only be equal to itself, as a result of Kolmogorov, the term "congruent" became standard in schools for figures that were previously called "equal", which popularized the term.[81]

While Euclid addressed proportionality and figures of the same shape, it wasn’t until the 17th century that the concept of similarity was formalized in the modern sense. Similar figures are those that have the same shape but can differ in size; they can be transformed into one another by scaling and congruence. Later a concept of equality of directed line segments, equipollence, was advanced by Giusto Bellavitis in 1835.

See also

- Template:Section link

- Homotopy type theory

- Identity type

- Inequality

- Logical equality

- Logical equivalence

- Proportionality (mathematics)

- Template:Section link

- Theory of pure equality

Notes

Template:Reflist Template:Notelist

References

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Citation

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite encyclopedia

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite dictionary

- ↑ Template:Cite dictionary

- ↑ Template:Cite encyclopedia

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book Here: §3.5, p. 103.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Sobolev, S.K. (originator). "Equation". Encyclopedia of Mathematics. Springer. Template:ISBN.

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Equation. Springer Encyclopedia of Mathematics. URL: http://encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=Equation&oldid=32613

- ↑ Henry Sinclair Hall, Samuel Ratcliffe Knight. Algebra for Beginners, 1895, p. 52

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Forrest, Peter, "The Identity of Indiscernibles", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL: https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/identity-indiscernible/#Form

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite encyclopedia

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Harvnb. Template:Harvnb. Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Template:Citation

- ↑ Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “Extensionality (n.)” December 2024

- ↑ Template:Harvnb. Template:Harvnb. Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb.

- ↑ Template:Harvnb. Template:Harvnb

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite web

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Alexander Karp & Bruce R. Vogeli – Russian Mathematics Education: Programs and Practices, Volume 5, pgs. 100–102