Plankalkül

Template:Short description Template:Distinguish Template:Use dmy dates Template:Use list-defined references Template:Infobox programming language Plankalkül (Template:IPA) is a programming language designed for engineering purposes by Konrad Zuse between 1942 and 1945. It was the first high-level programming language to be designed for a computer.

Kalkül (from Latin calculus) is the German term for a formal system—as in Hilbert-Kalkül, the original name for the Hilbert-style deduction system—so Plankalkül refers to a formal system for planning.[1]

History of programming

In the domain of creating computing machines, Zuse was self-taught, and developed them without knowledge about other mechanical computing machines that existed already – although later on (building the Z3) being inspired by Hilbert's and Ackermann's book on elementary mathematical logic (see Principles of Mathematical Logic).[2]Template:Rp To describe logical circuits, Zuse invented his own diagram and notation system, which he called "combinatorics of conditionals" (Template:Langx). After finishing the Z1 in 1938, Zuse discovered that the calculus he had independently devised already existed and was known as propositional calculus.[3]Template:Rp What Zuse had in mind, however, needed to be much more powerful (propositional calculus is not Turing-complete and is not able to describe even simple arithmetic calculations[4]). In May 1939, he described his plans for the development of what would become Plankalkül.[2]Template:Rp He wrote the following in his notebook:

While working on his doctoral dissertation, Zuse developed the first known formal system of algorithm notation[5]Template:Rp capable of handling branches and loops.[6]Template:Rp[2]Template:Rp In 1942 he began writing a chess program in Plankalkül.[2]Template:Rp In 1944, Zuse met with the German logician and philosopher Heinrich Scholz, who expressed appreciation for Zuse's utilization of logical calculus.[7] In 1945, Zuse described Plankalkül in an unpublished book.[8] The collapse of Nazi Germany, however, prevented him from submitting his manuscript.[6]Template:Rp

At that time the only two working computers in the world were ENIAC and Harvard Mark I, neither of which used a compiler, and ENIAC needed to be reprogrammed for each task by changing how the wires were connected.[3]Template:Rp

Although most of his computers were destroyed by Allied bombs, Zuse was able to rescue one machine, the Z4, and move it to the Alpine village of Hinterstein[5]Template:Rp (part of Bad Hindelang).

Unable to continue building computers – which was also forbidden by the Allied Powers[9] – Zuse devoted his time to the development of a higher-level programming model and language.[6]Template:Rp In 1948, he published a paper in the Archiv der Mathematik and presented at the Annual Meeting of the GAMM.[2]Template:Rp His work failed to attract much attention.Template:Citation needed In a 1957 lecture, Zuse expressed his hope that Plankalkül, "after some time as a Sleeping Beauty, will yet come to life."[3]Template:Rp He expressed disappointment that the designers of ALGOL 58 never acknowledged the influence of Plankalkül on their own work.[6]Template:Rp[5]Template:Rp

Plankalkül was republished with commentary in 1972.[10] The first compiler for Plankalkül was implemented by Joachim Hohmann in his 1975 dissertation.[11] Other independent implementations followed in 1998[12] and 2000 at the Free University of Berlin.[3]Template:Rp

Description

Plankalkül has drawn comparisons to the language APL, and to relational algebra. It includes assignment statements, subroutines, conditional statements, iteration, floating-point arithmetic, arrays, hierarchical record structures, assertions, exception handling, and other advanced features such as goal-directed execution. The Plankalkül provides a data structure called generalized graph (Template:Lang), which can be used to represent geometrical structures.[13]

Many features of the Plankalkül reappear in later programming languages; an exception is its idiosyncratic two-dimensional notation using multiple lines.

Some features of the Plankalkül:[2]Template:Rp

- only local variables

- functions do not support recursion

- only supports call by value

- composite types are arrays and tuples

- contains conditional expressions

- contains a for loop and a while loop

- no goto

Data types

The only primitive data type in the Plankalkül is a single bit or Boolean (Template:Langx – yes-no value in Zuse's terminology). It is denoted by the identifier . All the further data types are composite, and build up from primitive by means of "arrays" and "records".[14]Template:Rp

So, a sequence of eight bits (which in modern computing could be regarded as byte) is denoted by , and Boolean matrix of size by is described by . There also exists a shortened notation, so one could write instead of .[14]Template:Rp

Type could have two possible values and . So 4-bit sequence could be written like L00L, but in cases where such a sequence represents a number, the programmer could use the decimal representation 9.[14]Template:Rp

Record of two components and is written as .[14]Template:Rp

Type (Template:Langx) in Plankalkül consists of 3 elements: structured value (Template:Langx), pragmatic meaning (Template:Langx) and possible restriction on possible values (Template:Langx).[14]Template:Rp User defined types are identified by letter A with number, like – first user defined type.

Examples

Zuse used a lot of examples from chess theory:[14]Template:Rp

| Coordinate of chess board (it has size 8x8 so 3 bits are just enough) | ||

| square of the board (for example L00, 00L denotes e2 in algebraic notation) | ||

| piece (for example, 00L0 — white king) | ||

| piece on a board (for example L00, 00L; 00L0 — white king on e2) | ||

| board (pieces positions, describes which piece each of 64 squares contains) | ||

| game state ( — board, — player to move, — possibility of castling (2 for white and 2 for black), — information about cell on which en passant move is possible |

Identifiers

Identifiers are alphanumeric characters with a number.[14]Template:Rp There are the following kinds of identifiers for variables:[8]Template:Rp

- Input values (Template:Langx) — marked with a letter V.

- Intermediate, temporary values (Template:Langx) — marked with a letter Z.

- Constants (Template:Langx) — marked with a letter С.

- Output values (Template:Langx) — marked with a letter R.

Particular variable of some kind is identified by number, written under the kind.[14]Template:Rp For example:

- , , etc.

Programs and subprograms are marked with a letter P, followed by a program (and optionally a subprogram) number. For example , .[14]Template:Rp

Output value of program saved there in variable is available for other subprograms under the identifier , and reading value of that variable also means executing related subprogram.[14]Template:Rp

Accessing elements by index

Plankalkül allows access for separate elements of variable by using "component index" (Template:Langx). When, for example, program receives input in variable of type (game state), then — gives board state, — piece on square number i, and bit number j of that piece.[14]Template:Rp

In modern programming languages, that would be described by notation similar to V0[0], V0[0][i], V0[0][i][j] (although to access a single bit in modern programming languages a bitmask is typically used).

Two-dimensional syntax

Because indexes of variables are written vertically, each Plankalkül instruction requires multiple rows to write down.Template:Citation needed

First row contains variable kind, then variable number marked with letter V (Template:Langx), then indexes of variable subcomponents marked with K (Template:Langx), and then (Template:Langx) marked with S, which describes variable type. Type is not required, but Zuse notes that this helps with reading and understanding the program.[14]Template:Rp

In the line types and could be shortened to and .[14]Template:Rp

Examples:

| variable V3 — list of pairs of values of type | |

| Row K could be skipped when it is empty. Therefore, this expression means the same as above. | |

| Value of eights bit (index 7), of first (index 0) pair, of і-th element of variable V3, has Boolean type (). |

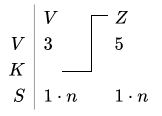

Indexes could be not only constants. Variables could be used as indexes for other variables, and that is marked with a line, which shows in which component index would value of variable be used:

|

Z5-th element of variable V3. Equivalent to expression V3[Z5] in many modern programming languages.[14]Template:Rp

|

Assignment operation

Zuse introduced in his calculus an assignment operator, unknown in mathematics before him. He marked it with «», and called it yields-sign (Template:Langx). Use of concept of assignment is one of the key differences between mathematics and computer science.[5]Template:Rp

Zuse wrote that the expression:

is analogous to the more traditional mathematical equation:

There are claims that Konrad Zuse initially used the glyph ![]() as a sign for assignment, and started to use under the influence of Heinz Rutishauser.[14]Template:Rp Knuth and Pardo believe that Zuse always wrote , and that

as a sign for assignment, and started to use under the influence of Heinz Rutishauser.[14]Template:Rp Knuth and Pardo believe that Zuse always wrote , and that ![]() was introduced by publishers of «Über den allgemeinen Plankalkül als Mittel zur Formulierung schematisch-kombinativer Aufgaben» in 1948.[5]Template:Rp In the ALGOL 58 conference in Zürich, European participants proposed to use the assignment character introduced by Zuse, but the American delegation insisted on

was introduced by publishers of «Über den allgemeinen Plankalkül als Mittel zur Formulierung schematisch-kombinativer Aufgaben» in 1948.[5]Template:Rp In the ALGOL 58 conference in Zürich, European participants proposed to use the assignment character introduced by Zuse, but the American delegation insisted on :=.[14]Template:Rp

The variable that stores the result of an assignment (l-value) is written to the right side of assignment operator.[5]Template:Rp The first assignment to the variable is considered to be a declaration.[14]Template:Rp

The left side of assignment operator is used for an expression (Template:Langx), that defines which value will be assigned to the variable. Expressions could use arithmetic operators, Boolean operators, and comparison operators ( etc.).[14]Template:Rp

The exponentiation operation is written similarly to the indexing operation - using lines in the two-dimensional notation:[8]Template:Rp

Control flow

Boolean values were represented as integers with Template:Code and Template:Code. Conditional control flow took the form of a guarded statement Template:Code, which executed the block Template:Code if Template:Code was true. There was also an iteration operator, of the form Template:Code} which repeats until all guards are false.[15]

Terminology

Zuse called a single program a Rechenplan ("computation plan"). He envisioned what he called a Planfertigungsgerät ("plan assembly device"), which would automatically translate the mathematical formulation of a program into machine-readable punched film stock, something today would be called a translator or compiler.[2]Template:Rp

Example

The original notation was two-dimensional.Template:Clarification needed For a later implementation in the 1990s, a linear notation was developed.

The following example defines a function max3 (in a linear transcription) that calculates the maximum of three variables:

P1 max3 (V0[:8.0],V1[:8.0],V2[:8.0]) → R0[:8.0] max(V0[:8.0],V1[:8.0]) → Z1[:8.0] max(Z1[:8.0],V2[:8.0]) → R0[:8.0] END P2 max (V0[:8.0],V1[:8.0]) → R0[:8.0] V0[:8.0] → Z1[:8.0] (Z1[:8.0] < V1[:8.0]) → V1[:8.0] → Z1[:8.0] Z1[:8.0] → R0[:8.0] END

See also

References

Further reading

- Template:Cite book

- Template:Cite journal (9 pages)

- Template:Cite book[1] (22 pages)

- Template:Cite web (24 pages)

External links

- Template:Cite web (NB. Plankalkül Java applets and documents.)

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedZenil_2012 - ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHellige_2004 - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedRojas-Göktekin-Friedland-Krüger-Kuniß-Langmack_2004 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTuring_2013 - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedKnuth-Pardo_1976 - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGiloi_1997 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedPetzold_1992 - ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedZuse_1945 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCoy_2004 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedZuse_1972 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHohmann_1979 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMauerer_2016 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGiloi_1990 - ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 14.12 14.13 14.14 14.15 14.16 14.17 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBauer-Wössner_1972 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedRojas_2001