Artin transfer (group theory): Difference between revisions

imported>Tpbradbury no its readable prose size is 43kb and 8000 words |

(No difference)

|

Latest revision as of 10:20, 9 December 2023

In the mathematical field of group theory, an Artin transfer is a certain homomorphism from an arbitrary finite or infinite group to the commutator quotient group of a subgroup of finite index. Originally, such mappings arose as group theoretic counterparts of class extension homomorphisms of abelian extensions of algebraic number fields by applying Artin's reciprocity maps to ideal class groups and analyzing the resulting homomorphisms between quotients of Galois groups. However, independently of number theoretic applications, a partial order on the kernels and targets of Artin transfers has recently turned out to be compatible with parent-descendant relations between finite p-groups (with a prime number p), which can be visualized in descendant trees. Therefore, Artin transfers provide a valuable tool for the classification of finite p-groups and for searching and identifying particular groups in descendant trees by looking for patterns defined by the kernels and targets of Artin transfers. These strategies of pattern recognition are useful in purely group theoretic context, as well as for applications in algebraic number theory concerning Galois groups of higher p-class fields and Hilbert p-class field towers.

Transversals of a subgroup

Let be a group and be a subgroup of finite index

Definitions.[1] A left transversal of in is an ordered system of representatives for the left cosets of in such that

Similarly a right transversal of in is an ordered system of representatives for the right cosets of in such that

Remark. For any transversal of in , there exists a unique subscript such that , resp. . Of course, this element with subscript which represents the principal coset (i.e., the subgroup itself) may be, but need not be, replaced by the neutral element .

Lemma.[2] Let be a non-abelian group with subgroup . Then the inverse elements of a left transversal of in form a right transversal of in . Moreover, if is a normal subgroup of , then any left transversal is also a right transversal of in .

- Proof. Since the mapping is an involution of we see that:

- For a normal subgroup we have for each .

We must check when the image of a transversal under a homomorphism is also a transversal.

Proposition. Let be a group homomorphism and be a left transversal of a subgroup in with finite index The following two conditions are equivalent:

- is a left transversal of the subgroup in the image with finite index

- Proof. As a mapping of sets maps the union to another union:

- but weakens the equality for the intersection to a trivial inclusion:

- Suppose for some :

- then there exists elements such that

- Then we have:

- Conversely if then there exists such that But the homomorphism maps the disjoint cosets to equal cosets:

Remark. We emphasize the important equivalence of the proposition in a formula:

Permutation representation

Suppose is a left transversal of a subgroup of finite index in a group . A fixed element gives rise to a unique permutation of the left cosets of in by left multiplication such that:

Using this we define a set of elements called the monomials associated with with respect to :

Similarly, if is a right transversal of in , then a fixed element gives rise to a unique permutation of the right cosets of in by right multiplication such that:

And we define the monomials associated with with respect to :

Definition.[1] The mappings:

are called the permutation representation of in the symmetric group with respect to and respectively.

Definition.[1] The mappings:

are called the monomial representation of in with respect to and respectively.

Lemma. For the right transversal associated to the left transversal , we have the following relations between the monomials and permutations corresponding to an element :

- Proof. For the right transversal , we have , for each . On the other hand, for the left transversal , we have

- This relation simultaneously shows that, for any , the permutation representations and the associated monomials are connected by and for each .

Artin transfer

Definitions.[2][3] Let be a group and a subgroup of finite index Assume is a left transversal of in with associated permutation representation such that

Similarly let be a right transversal of in with associated permutation representation such that

The Artin transfer with respect to is defined as:

Similarly we define:

Remarks. Isaacs[4] calls the mappings

the pre-transfer from to . The pre-transfer can be composed with a homomorphism from into an abelian group to define a more general version of the transfer from to via , which occurs in the book by Gorenstein.[5]

Taking the natural epimorphism

yields the preceding definition of the Artin transfer in its original form by Schur[2] and by Emil Artin,[3] which has also been dubbed Verlagerung by Hasse.[6] Note that, in general, the pre-transfer is neither independent of the transversal nor a group homomorphism.

Independence of the transversal

Proposition.[1][2][4][5][7][8][9] The Artin transfers with respect to any two left transversals of in coincide.

- Proof. Let and be two left transversals of in . Then there exists a unique permutation such that:

- Consequently:

- For a fixed element , there exists a unique permutation such that:

- Therefore, the permutation representation of with respect to is given by which yields: Furthermore, for the connection between the two elements:

- we have:

- Finally since is abelian and and are permutations, the Artin transfer turns out to be independent of the left transversal:

- as defined in formula (5).

Proposition. The Artin transfers with respect to any two right transversals of in coincide.

- Proof. Similar to the previous proposition.

Proposition. The Artin transfers with respect to and coincide.

- Proof. Using formula (4) and being abelian we have:

- The last step is justified by the fact that the Artin transfer is a homomorphism. This will be shown in the following section.

Corollary. The Artin transfer is independent of the choice of transversals and only depends on and .

Artin transfers as homomorphisms

Theorem.[1][2][4][5][7][8][9] Let be a left transversal of in . The Artin transfer

and the permutation representation:

are group homomorphisms:

Template:Hidden begin Let :

Since is abelian and is a permutation, we can change the order of the factors in the product:

This relation simultaneously shows that the Artin transfer and the permutation representation are homomorphisms. Template:Hidden end

It is illuminating to restate the homomorphism property of the Artin transfer in terms of the monomial representation. The images of the factors are given by

In the last proof, the image of the product turned out to be

- ,

which is a very peculiar law of composition discussed in more detail in the following section.

The law is reminiscent of crossed homomorphisms in the first cohomology group of a -module , which have the property for .

Wreath product of H and S(n)

The peculiar structures which arose in the previous section can also be interpreted by endowing the cartesian product with a special law of composition known as the wreath product of the groups and with respect to the set

Definition. For , the wreath product of the associated monomials and permutations is given by

Theorem.[1][7] With this law of composition on the monomial representation

is an injective homomorphism.

Template:Hidden begin The homomorphism property has been shown above already. For a homomorphism to be injective, it suffices to show the triviality of its kernel. The neutral element of the group endowed with the wreath product is given by , where the last means the identity permutation. If , for some , then and consequently

Finally, an application of the inverse inner automorphism with yields , as required for injectivity. Template:Hidden end

Remark. The monomial representation of the theorem stands in contrast to the permutation representation, which cannot be injective if

Remark. Whereas Huppert[1] uses the monomial representation for defining the Artin transfer, we prefer to give the immediate definitions in formulas (5) and (6) and to merely illustrate the homomorphism property of the Artin transfer with the aid of the monomial representation.

Composition of Artin transfers

Theorem.[1][7] Let be a group with nested subgroups such that and Then the Artin transfer is the compositum of the induced transfer and the Artin transfer , that is:

- .

Template:Hidden begin If is a left transversal of in and is a left transversal of in , that is and , then

is a disjoint left coset decomposition of with respect to .

Given two elements and , there exist unique permutations , and , such that

Then, anticipating the definition of the induced transfer, we have

For each pair of subscripts and , we put , and we obtain

resp.

Therefore, the image of under the Artin transfer is given by

Finally, we want to emphasize the structural peculiarity of the monomial representation

which corresponds to the composite of Artin transfers, defining

for a permutation , and using the symbolic notation for all pairs of subscripts , .

The preceding proof has shown that

Therefore, the action of the permutation on the set is given by . The action on the second component depends on the first component (via the permutation ), whereas the action on the first component is independent of the second component . Therefore, the permutation can be identified with the multiplet

which will be written in twisted form in the next section.

Wreath product of S(m) and S(n)

The permutations , which arose as second components of the monomial representation

in the previous section, are of a very special kind. They belong to the stabilizer of the natural equipartition of the set into the rows of the corresponding matrix (rectangular array). Using the peculiarities of the composition of Artin transfers in the previous section, we show that this stabilizer is isomorphic to the wreath product of the symmetric groups and with respect to the set , whose underlying set is endowed with the following law of composition:

This law reminds of the chain rule for the Fréchet derivative in of the compositum of differentiable functions and between complete normed spaces.

The above considerations establish a third representation, the stabilizer representation,

of the group in the wreath product , similar to the permutation representation and the monomial representation. As opposed to the latter, the stabilizer representation cannot be injective, in general. For instance, certainly not, if is infinite. Formula (10) proves the following statement.

Theorem. The stabilizer representation

of the group in the wreath product of symmetric groups is a group homomorphism.

Cycle decomposition

Let be a left transversal of a subgroup of finite index in a group and be its associated permutation representation.

Theorem.[1][3][4][5][8][9] Suppose the permutation decomposes into pairwise disjoint (and thus commuting) cycles of lengths which is unique up to the ordering of the cycles. More explicitly, suppose

for , and Then the image of under the Artin transfer is given by

Template:Hidden begin Define for and . This is a left transversal of in since

is a disjoint decomposition of into left cosets of .

Fix a value of . Then:

Define:

Consequently,

The cycle decomposition corresponds to a double coset decomposition of :

It was this cycle decomposition form of the transfer homomorphism which was given by E. Artin in his original 1929 paper.[3]

Transfer to a normal subgroup

Let be a normal subgroup of finite index in a group . Then we have , for all , and there exists the quotient group of order . For an element , we let denote the order of the coset in , and we let be a left transversal of the subgroup in , where .

Theorem. Then the image of under the Artin transfer is given by:

- .

Template:Hidden begin is a cyclic subgroup of order in , and a left transversal of the subgroup in , where and is the corresponding disjoint left coset decomposition, can be refined to a left transversal with disjoint left coset decomposition:

of in . Hence, the formula for the image of under the Artin transfer in the previous section takes the particular shape

with exponent independent of . Template:Hidden end

Corollary. In particular, the inner transfer of an element is given as a symbolic power:

with the trace element

of in as symbolic exponent.

The other extreme is the outer transfer of an element which generates , that is .

It is simply an th power

- .

Template:Hidden begin The inner transfer of an element , whose coset is the principal set in of order , is given as the symbolic power

with the trace element

of in as symbolic exponent.

The outer transfer of an element which generates , that is , whence the coset is generator of with order, is given as the th power

Transfers to normal subgroups will be the most important cases in the sequel, since the central concept of this article, the Artin pattern, which endows descendant trees with additional structure, consists of targets and kernels of Artin transfers from a group to intermediate groups between and . For these intermediate groups we have the following lemma.

Lemma. All subgroups containing the commutator subgroup are normal.

Template:Hidden begin Let . If were not a normal subgroup of , then we had for some element . This would imply the existence of elements and such that , and consequently the commutator would be an element in in contradiction to . Template:Hidden end

Explicit implementations of Artin transfers in the simplest situations are presented in the following section.

Computational implementation

Abelianization of type (p,p)

Let be a p-group with abelianization of elementary abelian type . Then has maximal subgroups of index

Lemma. In this particular case, the Frattini subgroup, which is defined as the intersection of all maximal subgroups coincides with the commutator subgroup.

Proof. To see this note that due to the abelian type of the commutator subgroup contains all p-th powers and thus we have .

For each , let be the Artin transfer homomorphism. According to Burnside's basis theorem the group can therefore be generated by two elements such that For each of the maximal subgroups , which are also normal we need a generator with respect to , and a generator of a transversal such that

A convenient selection is given by

Then, for each we use equations (16) and (18) to implement the inner and outer transfers:

- ,

The reason is that in and

The complete specification of the Artin transfers also requires explicit knowledge of the derived subgroups . Since is a normal subgroup of index in , a certain general reduction is possible by [10] but a presentation of must be known for determining generators of , whence

Abelianization of type (p2,p)

Let be a p-group with abelianization of non-elementary abelian type . Then has maximal subgroups of index and subgroups of index For each let

be the Artin transfer homomorphisms. Burnside's basis theorem asserts that the group can be generated by two elements such that

We begin by considering the first layer of subgroups. For each of the normal subgroups , we select a generator

such that . These are the cases where the factor group is cyclic of order . However, for the distinguished maximal subgroup , for which the factor group is bicyclic of type , we need two generators:

such that . Further, a generator of a transversal must be given such that , for each . It is convenient to define

Then, for each , we have inner and outer transfers:

since and .

Now we continue by considering the second layer of subgroups. For each of the normal subgroups , we select a generator

such that . Among these subgroups, the Frattini subgroup is particularly distinguished. A uniform way of defining generators of a transversal such that , is to set

Since , but on the other hand and , for , with the single exception that , we obtain the following expressions for the inner and outer transfers

exceptionally

The structure of the derived subgroups and must be known to specify the action of the Artin transfers completely.

Transfer kernels and targets

Let be a group with finite abelianization . Suppose that denotes the family of all subgroups which contain and are therefore necessarily normal, enumerated by a finite index set . For each , let be the Artin transfer from to the abelianization .

Definition.[11] The family of normal subgroups is called the transfer kernel type (TKT) of with respect to , and the family of abelianizations (resp. their abelian type invariants) is called the transfer target type (TTT) of with respect to . Both families are also called multiplets whereas a single component will be referred to as a singulet.

Important examples for these concepts are provided in the following two sections.

Abelianization of type (p,p)

Let be a p-group with abelianization of elementary abelian type . Then has maximal subgroups of index . For let denote the Artin transfer homomorphism.

Definition. The family of normal subgroups is called the transfer kernel type (TKT) of with respect to .

Remark. For brevity, the TKT is identified with the multiplet , whose integer components are given by

Here, we take into consideration that each transfer kernel must contain the commutator subgroup of , since the transfer target is abelian. However, the minimal case cannot occur.

Remark. A renumeration of the maximal subgroups and of the transfers by means of a permutation gives rise to a new TKT with respect to , identified with , where

It is adequate to view the TKTs as equivalent. Since we have

the relation between and is given by . Therefore, is another representative of the orbit of under the action of the symmetric group on the set of all mappings from where the extension of the permutation is defined by and formally

Definition. The orbit of any representative is an invariant of the p-group and is called its transfer kernel type, briefly TKT.

Remark. Let denote the counter of total transfer kernels , which is an invariant of the group . In 1980, S. M. Chang and R. Foote[12] proved that, for any odd prime and for any integer , there exist metabelian p-groups having abelianization of type such that . However, for , there do not exist non-abelian -groups with , which must be metabelian of maximal class, such that . Only the elementary abelian -group has . See Figure 5.

In the following concrete examples for the counters , and also in the remainder of this article, we use identifiers of finite p-groups in the SmallGroups Library by H. U. Besche, B. Eick and E. A. O'Brien.[13][14]

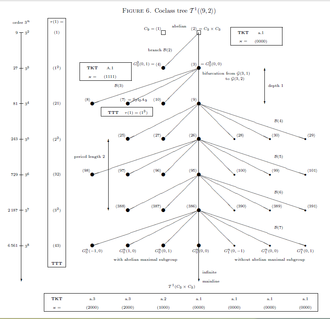

For , we have

- for the extra special group of exponent with TKT (Figure 6),

- for the two groups with TKTs (Figures 8 and 9),

- for the group with TKT (Figure 4 in the article on descendant trees),

- for the group with TKT (Figure 6),

- for the extra special group of exponent with TKT (Figure 6).

Abelianization of type (p2,p)

Let be a p-group with abelianization of non-elementary abelian type Then possesses maximal subgroups of index and subgroups of index

Assumption. Suppose

is the distinguished maximal subgroup and

is the distinguished subgroup of index which as the intersection of all maximal subgroups, is the Frattini subgroup of .

First layer

For each , let denote the Artin transfer homomorphism.

Definition. The family is called the first layer transfer kernel type of with respect to and , and is identified with , where

Remark. Here, we observe that each first layer transfer kernel is of exponent with respect to and consequently cannot coincide with for any , since is cyclic of order , whereas is bicyclic of type .

Second layer

For each , let be the Artin transfer homomorphism from to the abelianization of .

Definition. The family is called the second layer transfer kernel type of with respect to and , and is identified with where

Transfer kernel type

Combining the information on the two layers, we obtain the (complete) transfer kernel type of the p-group with respect to and .

Remark. The distinguished subgroups and are unique invariants of and should not be renumerated. However, independent renumerations of the remaining maximal subgroups and the transfers by means of a permutation , and of the remaining subgroups of index and the transfers by means of a permutation , give rise to new TKTs with respect to and , identified with , where

and with respect to and , identified with where

It is adequate to view the TKTs and as equivalent. Since we have

the relations between and , and and , are given by

Therefore, is another representative of the orbit of under the action:

of the product of two symmetric groups on the set of all pairs of mappings , where the extensions and of a permutation are defined by and , and formally and

Definition. The orbit of any representative is an invariant of the p-group and is called its transfer kernel type, briefly TKT.

Connections between layers

The Artin transfer is the composition of the induced transfer from to and the Artin transfer

There are two options regarding the intermediate subgroups

- For the subgroups only the distinguished maximal subgroup is an intermediate subgroup.

- For the Frattini subgroup all maximal subgroups are intermediate subgroups.

- This causes restrictions for the transfer kernel type of the second layer, since

- and thus

- But even

- Furthermore, when with an element of order with respect to , can belong to only if its th power is contained in , for all intermediate subgroups , and thus: , for certain , enforces the first layer TKT singulet , but , for some , even specifies the complete first layer TKT multiplet , that is , for all .

Inheritance from quotients

The common feature of all parent-descendant relations between finite p-groups is that the parent is a quotient of the descendant by a suitable normal subgroup Thus, an equivalent definition can be given by selecting an epimorphism with Then the group can be viewed as the parent of the descendant .

In the following sections, this point of view will be taken, generally for arbitrary groups, not only for finite p-groups.

Passing through the abelianization

- Proposition. Suppose is an abelian group and is a homomorphism. Let denote the canonical projection map. Then there exists a unique homomorphism such that and (See Figure 1).

Proof. This statement is a consequence of the second Corollary in the article on the induced homomorphism. Nevertheless, we give an independent proof for the present situation: the uniqueness of is a consequence of the condition which implies for any we have:

is a homomorphism, let be arbitrary, then:

Thus, the commutator subgroup , and this finally shows that the definition of is independent of the coset representative,

TTT singulets

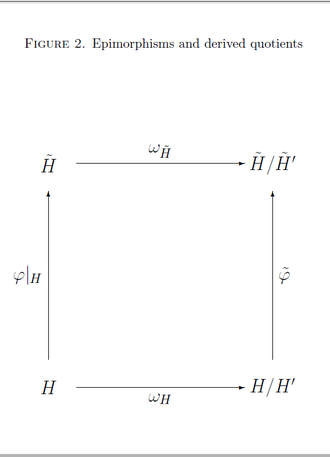

- Proposition. Assume are as above and is the image of a subgroup The commutator subgroup of is the image of the commutator subgroup of Therefore, induces a unique epimorphism , and thus is a quotient of Moreover, if , then the map is an isomorphism (See Figure 2).

Proof. This claim is a consequence of the Main Theorem in the article on the induced homomorphism. Nevertheless, an independent proof is given as follows: first, the image of the commutator subgroup is

Second, the epimorphism can be restricted to an epimorphism . According to the previous section, the composite epimorphism factors through by means of a uniquely determined epimorphism such that . Consequently, we have . Furthermore, the kernel of is given explicitly by .

Finally, if , then is an isomorphism, since .

Definition.[15] Due to the results in the present section, it makes sense to define a partial order on the set of abelian type invariants by putting , when , and , when .

TKT singulets

- Proposition. Assume are as above and is the image of a subgroup of finite index Let and be Artin transfers. If , then the image of a left transversal of in is a left transversal of in , and Moreover, if then (See Figure 3).

Proof. Let be a left transversal of in . Then we have a disjoint union:

Consider the image of this disjoint union, which is not necessarily disjoint,

and let We have:

Let be the epimorphism from the previous proposition. We have:

Since , the right hand side equals , if is a left transversal of in , which is true when Therefore, Consequently, implies the inclusion

Finally, if , then by the previous proposition is an isomorphism. Using its inverse we get , which proves

Combining the inclusions we have:

Definition.[15] In view of the results in the present section, we are able to define a partial order of transfer kernels by setting , when

TTT and TKT multiplets

Assume are as above and that and are isomorphic and finite. Let denote the family of all subgroups containing (making it a finite family of normal subgroups). For each let:

Take be any non-empty subset of . Then it is convenient to define , called the (partial) transfer kernel type (TKT) of with respect to , and called the (partial) transfer target type (TTT) of with respect to .

Due to the rules for singulets, established in the preceding two sections, these multiplets of TTTs and TKTs obey the following fundamental inheritance laws:

- Inheritance Law I. If , then , in the sense that , for each , and , in the sense that , for each .

- Inheritance Law II. If , then , in the sense that , for each , and , in the sense that , for each .

Inherited automorphisms

A further inheritance property does not immediately concern Artin transfers but will prove to be useful in applications to descendant trees.

- Inheritance Law III. Assume are as above and If then there exists a unique epimorphism such that . If then

Proof. Using the isomorphism we define:

First we show this map is well-defined:

The fact that is surjective, a homomorphism and satisfies are easily verified.

And if , then injectivity of is a consequence of

Let be the canonical projection then there exists a unique induced automorphism such that , that is,

The reason for the injectivity of is that

since is a characteristic subgroup of .

Definition. is called a σ−group, if there exists such that the induced automorphism acts like the inversion on , that is for all

The Inheritance Law III asserts that, if is a σ−group and , then is also a σ−group, the required automorphism being . This can be seen by applying the epimorphism to the equation which yields

Stabilization criteria

In this section, the results concerning the inheritance of TTTs and TKTs from quotients in the previous section are applied to the simplest case, which is characterized by the following

Assumption. The parent of a group is the quotient of by the last non-trivial term of the lower central series of , where denotes the nilpotency class of . The corresponding epimorphism from onto is the canonical projection, whose kernel is given by .

Under this assumption, the kernels and targets of Artin transfers turn out to be compatible with parent-descendant relations between finite p-groups.

Compatibility criterion. Let be a prime number. Suppose that is a non-abelian finite p-group of nilpotency class . Then the TTT and the TKT of and of its parent are comparable in the sense that and .

The simple reason for this fact is that, for any subgroup , we have , since .

For the remaining part of this section, the investigated groups are supposed to be finite metabelian p-groups with elementary abelianization of rank , that is of type .

Partial stabilization for maximal class. A metabelian p-group of coclass and of nilpotency class shares the last components of the TTT and of the TKT with its parent . More explicitly, for odd primes , we have and for . [16]

This criterion is due to the fact that implies , [17] for the last maximal subgroups of .

The condition is indeed necessary for the partial stabilization criterion. For odd primes , the extra special -group of order and exponent has nilpotency class only, and the last components of its TKT are strictly smaller than the corresponding components of the TKT of its parent which is the elementary abelian -group of type . [16] For , both extra special -groups of coclass and class , the ordinary quaternion group with TKT and the dihedral group with TKT , have strictly smaller last two components of their TKTs than their common parent with TKT .

Total stabilization for maximal class and positive defect.

A metabelian p-group of coclass and of nilpotency class , that is, with index of nilpotency , shares all components of the TTT and of the TKT with its parent , provided it has positive defect of commutativity . [11] Note that implies , and we have for all . [16]

This statement can be seen by observing that the conditions and imply , [17] for all the maximal subgroups of .

The condition is indeed necessary for total stabilization. To see this it suffices to consider the first component of the TKT only. For each nilpotency class , there exist (at least) two groups with TKT and with TKT , both with defect , where the first component of their TKT is strictly smaller than the first component of the TKT of their common parent .

Partial stabilization for non-maximal class.

Let be fixed. A metabelian 3-group with abelianization , coclass and nilpotency class shares the last two (among the four) components of the TTT and of the TKT with its parent .

This criterion is justified by the following consideration. If , then [17] for the last two maximal subgroups of .

The condition is indeed unavoidable for partial stabilization, since there exist several -groups of class , for instance those with SmallGroups identifiers , such that the last two components of their TKTs are strictly smaller than the last two components of the TKT of their common parent .

Total stabilization for non-maximal class and cyclic centre.

Again, let be fixed. A metabelian 3-group with abelianization , coclass , nilpotency class and cyclic centre shares all four components of the TTT and of the TKT with its parent .

The reason is that, due to the cyclic centre, we have [17] for all four maximal subgroups of .

The condition of a cyclic centre is indeed necessary for total stabilization, since for a group with bicyclic centre there occur two possibilities. Either is also bicyclic, whence is never contained in , or is cyclic but is never contained in .

Summarizing, we can say that the last four criteria underpin the fact that Artin transfers provide a marvellous tool for classifying finite p-groups.

In the following sections, it will be shown how these ideas can be applied for endowing descendant trees with additional structure, and for searching particular groups in descendant trees by looking for patterns defined by the kernels and targets of Artin transfers. These strategies of pattern recognition are useful in pure group theory and in algebraic number theory.

Structured descendant trees (SDTs)

This section uses the terminology of descendant trees in the theory of finite p-groups. In Figure 4, a descendant tree with modest complexity is selected exemplarily to demonstrate how Artin transfers provide additional structure for each vertex of the tree. More precisely, the underlying prime is , and the chosen descendant tree is actually a coclass tree having a unique infinite mainline, branches of depth , and strict periodicity of length setting in with branch . The initial pre-period consists of branches and with exceptional structure. Branches and form the primitive period such that , for odd , and , for even . The root of the tree is the metabelian -group with identifier , that is, a group of order and with counting number . This root is not coclass settled, whence its entire descendant tree is of considerably higher complexity than the coclass- subtree , whose first six branches are drawn in the diagram of Figure 4. The additional structure can be viewed as a sort of coordinate system in which the tree is embedded. The horizontal abscissa is labelled with the transfer kernel type (TKT) , and the vertical ordinate is labelled with a single component of the transfer target type (TTT). The vertices of the tree are drawn in such a manner that members of periodic infinite sequences form a vertical column sharing a common TKT. On the other hand, metabelian groups of a fixed order, represented by vertices of depth at most , form a horizontal row sharing a common first component of the TTT. (To discourage any incorrect interpretations, we explicitly point out that the first component of the TTT of non-metabelian groups or metabelian groups, represented by vertices of depth , is usually smaller than expected, due to stabilization phenomena!) The TTT of all groups in this tree represented by a big full disk, which indicates a bicyclic centre of type , is given by with varying first component , the nearly homocyclic abelian -group of order , and fixed further components and , where the abelian type invariants are either written as orders of cyclic components or as their -logarithms with exponents indicating iteration. (The latter notation is employed in Figure 4.) Since the coclass of all groups in this tree is , the connection between the order and the nilpotency class is given by .

Pattern recognition

For searching a particular group in a descendant tree by looking for patterns defined by the kernels and targets of Artin transfers, it is frequently adequate to reduce the number of vertices in the branches of a dense tree with high complexity by sifting groups with desired special properties, for example

- filtering the -groups,

- eliminating a set of certain transfer kernel types,

- cancelling all non-metabelian groups (indicated by small contour squares in Fig. 4),

- removing metabelian groups with cyclic centre (denoted by small full disks in Fig. 4),

- cutting off vertices whose distance from the mainline (depth) exceeds some lower bound,

- combining several different sifting criteria.

The result of such a sieving procedure is called a pruned descendant tree with respect to the desired set of properties. However, in any case, it should be avoided that the main line of a coclass tree is eliminated, since the result would be a disconnected infinite set of finite graphs instead of a tree. For example, it is neither recommended to eliminate all -groups in Figure 4 nor to eliminate all groups with TKT . In Figure 4, the big double contour rectangle surrounds the pruned coclass tree , where the numerous vertices with TKT are completely eliminated. This would, for instance, be useful for searching a -group with TKT and first component of the TTT. In this case, the search result would even be a unique group. We expand this idea further in the following detailed discussion of an important example.

Historical example

The oldest example of searching for a finite p-group by the strategy of pattern recognition via Artin transfers goes back to 1934, when A. Scholz and O. Taussky [18] tried to determine the Galois group of the Hilbert -class field tower, that is the maximal unramified pro- extension , of the complex quadratic number field They actually succeeded in finding the maximal metabelian quotient of , that is the Galois group of the second Hilbert -class field of . However, it needed years until M. R. Bush and D. C. Mayer, in 2012, provided the first rigorous proof [15] that the (potentially infinite) -tower group coincides with the finite -group of derived length , and thus the -tower of has exactly three stages, stopping at the third Hilbert -class field of .

| c | order of Pc |

SmallGroups identifier of Pc |

TKT of Pc |

TTT of Pc |

ν | μ | descendant numbers of Pc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

The search is performed with the aid of the p-group generation algorithm by M. F. Newman [19] and E. A. O'Brien. [20] For the initialization of the algorithm, two basic invariants must be determined. Firstly, the generator rank of the p-groups to be constructed. Here, we have and is given by the -class rank of the quadratic field . Secondly, the abelian type invariants of the -class group of . These two invariants indicate the root of the descendant tree which will be constructed successively. Although the p-group generation algorithm is designed to use the parent-descendant definition by means of the lower exponent-p central series, it can be fitted to the definition with the aid of the usual lower central series. In the case of an elementary abelian p-group as root, the difference is not very big. So we have to start with the elementary abelian -group of rank two, which has the SmallGroups identifier , and to construct the descendant tree . We do that by iterating the p-group generation algorithm, taking suitable capable descendants of the previous root as the next root, always executing an increment of the nilpotency class by a unit.

As explained at the beginning of the section Pattern recognition, we must prune the descendant tree with respect to the invariants TKT and TTT of the -tower group , which are determined by the arithmetic of the field as (exactly two fixed points and no transposition) and . Further, any quotient of must be a -group, enforced by number theoretic requirements for the quadratic field .

The root has only a single capable descendant of type . In terms of the nilpotency class, is the class- quotient of and is the class- quotient of . Since the latter has nuclear rank two, there occurs a bifurcation , where the former component can be eliminated by the stabilization criterion for the TKT of all -groups of maximal class.

Due to the inheritance property of TKTs, only the single capable descendant qualifies as the class- quotient of . There is only a single capable -group among the descendants of . It is the class- quotient of and has nuclear rank two.

This causes the essential bifurcation in two subtrees belonging to different coclass graphs and . The former contains the metabelian quotient of with two possibilities , which are not balanced with relation rank bigger than the generator rank. The latter consists entirely of non-metabelian groups and yields the desired -tower group as one among the two Schur -groups and with .

Finally the termination criterion is reached at the capable vertices and , since the TTT is too big and will even increase further, never returning to . The complete search process is visualized in Table 1, where, for each of the possible successive p-quotients of the -tower group of , the nilpotency class is denoted by , the nuclear rank by , and the p-multiplicator rank by .

Commutator calculus

This section shows exemplarily how commutator calculus can be used for determining the kernels and targets of Artin transfers explicitly. As a concrete example we take the metabelian -groups with bicyclic centre, which are represented by big full disks as vertices, of the coclass tree diagram in Figure 4. They form ten periodic infinite sequences, four, resp. six, for even, resp. odd, nilpotency class , and can be characterized with the aid of a parametrized polycyclic power-commutator presentation:

where is the nilpotency class, with is the order, and are parameters.

The transfer target type (TTT) of the group depends only on the nilpotency class , is independent of the parameters , and is given uniformly by . This phenomenon is called a polarization, more precisely a uni-polarization,[11] at the first component.

The transfer kernel type (TKT) of the group is independent of the nilpotency class , but depends on the parameters , and is given by c.18, , for (a mainline group), H.4, , for (two capable groups), E.6, , for (a terminal group), and E.14, , for (two terminal groups). For even nilpotency class, the two groups of types H.4 and E.14, which differ in the sign of the parameter only, are isomorphic.

These statements can be deduced by means of the following considerations.

As a preparation, it is useful to compile a list of some commutator relations, starting with those given in the presentation, for and for , which shows that the bicyclic centre is given by . By means of the right product rule and the right power rule , we obtain , , and , for .

The maximal subgroups of are taken in a similar way as in the section on the computational implementation, namely

Their derived subgroups are crucial for the behavior of the Artin transfers. By making use of the general formula , where , and where we know that in the present situation, it follows that

Note that is not far from being abelian, since is contained in the centre .

As the first main result, we are now in the position to determine the abelian type invariants of the derived quotients:

the unique quotient which grows with increasing nilpotency class , since for even and for odd ,

since generally , but for , whereas for and .

Now we come to the kernels of the Artin transfer homomorphisms . It suffices to investigate the induced transfers and to begin by finding expressions for the images of elements , which can be expressed in the form

First, we exploit outer transfers as much as possible:

Next, we treat the unavoidable inner transfers, which are more intricate. For this purpose, we use the polynomial identity

to obtain:

Finally, we combine the results: generally

and in particular,

To determine the kernels, it remains to solve the equations:

The following equivalences, for any , finish the justification of the statements:

- both arbitrary .

- with arbitrary ,

- with arbitrary ,

- ,

Consequently, the last three components of the TKT are independent of the parameters which means that both, the TTT and the TKT, reveal a uni-polarization at the first component.

Systematic library of SDTs

The aim of this section is to present a collection of structured coclass trees (SCTs) of finite p-groups with parametrized presentations and a succinct summary of invariants. The underlying prime is restricted to small values . The trees are arranged according to increasing coclass and different abelianizations within each coclass. To keep the descendant numbers manageable, the trees are pruned by eliminating vertices of depth bigger than one. Further, we omit trees where stabilization criteria enforce a common TKT of all vertices, since we do not consider such trees as structured any more. The invariants listed include

- pre-period and period length,

- depth and width of branches,

- uni-polarization, TTT and TKT,

- -groups.

We refrain from giving justifications for invariants, since the way how invariants are derived from presentations was demonstrated exemplarily in the section on commutator calculus

Coclass 1

For each prime , the unique tree of p-groups of maximal class is endowed with information on TTTs and TKTs, that is, for for , and for . In the last case, the tree is restricted to metabelian -groups.

The -groups of coclass in Figure 5 can be defined by the following parametrized polycyclic pc-presentation, quite different from Blackburn's presentation.[10]

where the nilpotency class is , the order is with , and are parameters. The branches are strictly periodic with pre-period and period length , and have depth and width . Polarization occurs for the third component and the TTT is , only dependent on and with cyclic . The TKT depends on the parameters and is for the dihedral mainline vertices with , for the terminal generalized quaternion groups with , and for the terminal semi dihedral groups with . There are two exceptions, the abelian root with and , and the usual quaternion group with and .

The -groups of coclass in Figure 6 can be defined by the following parametrized polycyclic pc-presentation, slightly different from Blackburn's presentation.[10]

where the nilpotency class is , the order is with , and are parameters. The branches are strictly periodic with pre-period and period length , and have depth and width . Polarization occurs for the first component and the TTT is , only dependent on and . The TKT depends on the parameters and is for the mainline vertices with for the terminal vertices with for the terminal vertices with , and for the terminal vertices with . There exist three exceptions, the abelian root with , the extra special group of exponent with and , and the Sylow -subgroup of the alternating group with . Mainline vertices and vertices on odd branches are -groups.

The metabelian -groups of coclass in Figure 7 can be defined by the following parametrized polycyclic pc-presentation, slightly different from Miech's presentation.[21]

where the nilpotency class is , the order is with , and are parameters. The (metabelian!) branches are strictly periodic with pre-period and period length , and have depth and width . (The branches of the complete tree, including non-metabelian groups, are only virtually periodic and have bounded width but unbounded depth!) Polarization occurs for the first component and the TTT is , only dependent on and the defect of commutativity . The TKT depends on the parameters and is for the mainline vertices with for the terminal vertices with for the terminal vertices with , and for the vertices with . There exist three exceptions, the abelian root with , the extra special group of exponent with and , and the group with . Mainline vertices and vertices on odd branches are -groups.

Coclass 2

Abelianization of type (p,p)

Three coclass trees, , and for , are endowed with information concerning TTTs and TKTs.

On the tree , the -groups of coclass with bicyclic centre in Figure 8 can be defined by the following parametrized polycyclic pc-presentation. [11]

where the nilpotency class is , the order is with , and are parameters. The branches are strictly periodic with pre-period and period length , and have depth and width . Polarization occurs for the first component and the TTT is , only dependent on . The TKT depends on the parameters and is for the mainline vertices with , for the capable vertices with , for the terminal vertices with , and for the terminal vertices with . Mainline vertices and vertices on even branches are -groups.

On the tree , the -groups of coclass with bicyclic centre in Figure 9 can be defined by the following parametrized polycyclic pc-presentation. [11]

where the nilpotency class is , the order is with , and are parameters. The branches are strictly periodic with pre-period and period length , and have depth and width . Polarization occurs for the second component and the TTT is , only dependent on . The TKT depends on the parameters and is for the mainline vertices with , for the capable vertices with , for the terminal vertices with , and for the terminal vertices with . Mainline vertices and vertices on even branches are -groups.

Abelianization of type (p2,p)

and for , and for .

Abelianization of type (p,p,p)

for , and for .

Coclass 3

Abelianization of type (p2,p)

, and for .

Abelianization of type (p,p,p)

and for , and for .

Arithmetical applications

In algebraic number theory and class field theory, structured descendant trees (SDTs) of finite p-groups provide an excellent tool for

- visualizing the location of various non-abelian p-groups associated with algebraic number fields ,

- displaying additional information about the groups in labels attached to corresponding vertices, and

- emphasizing the periodicity of occurrences of the groups on branches of coclass trees.

For instance, let be a prime number, and assume that denotes the second Hilbert p-class field of an algebraic number field , that is the maximal metabelian unramified extension of of degree a power of . Then the second p-class group of is usually a non-abelian p-group of derived length and frequently permits to draw conclusions about the entire p-class field tower of , that is the Galois group of the maximal unramified pro-p extension of .

Given a sequence of algebraic number fields with fixed signature , ordered by the absolute values of their discriminants , a suitable structured coclass tree (SCT) , or also the finite sporadic part of a coclass graph , whose vertices are entirely or partially realized by second p-class groups of the fields is endowed with additional arithmetical structure when each realized vertex , resp. , is mapped to data concerning the fields such that .

Example

To be specific, let and consider complex quadratic fields with fixed signature having -class groups with type invariants . See OEIS A242863 [1]. Their second -class groups have been determined by D. C. Mayer [17] for the range , and, most recently, by N. Boston, M. R. Bush and F. Hajir[22] for the extended range .

Let us firstly select the two structured coclass trees (SCTs) and , which are known from Figures 8 and 9 already, and endow these trees with additional arithmetical structure by surrounding a realized vertex with a circle and attaching an adjacent underlined boldface integer which gives the minimal absolute discriminant such that is realized by the second -class group . Then we obtain the arithmetically structured coclass trees (ASCTs) in Figures 10 and 11, which, in particular, give an impression of the actual distribution of second -class groups.[11] See OEIS A242878 [2].

| State |

TKT E.14 |

TKT E.6 |

TKT H.4 |

TKT E.9 |

TKT E.8 |

TKT G.16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GS | ||||||

| ES1 | ||||||

| ES2 | ||||||

| ES3 | ||||||

| ES4 |

Concerning the periodicity of occurrences of second -class groups of complex quadratic fields, it was proved[17] that only every other branch of the trees in Figures 10 and 11 can be populated by these metabelian -groups and that the distribution sets in with a ground state (GS) on branch and continues with higher excited states (ES) on the branches with even . This periodicity phenomenon is underpinned by three sequences with fixed TKTs [16]

on the ASCT , and by three sequences with fixed TKTs [16]

on the ASCT . Up to now,[22] the ground state and three excited states are known for each of the six sequences, and for TKT E.9 even the fourth excited state occurred already. The minimal absolute discriminants of the various states of each of the six periodic sequences are presented in Table 2. Data for the ground states (GS) and the first excited states (ES1) has been taken from D. C. Mayer,[17] most recent information on the second, third and fourth excited states (ES2, ES3, ES4) is due to N. Boston, M. R. Bush and F. Hajir. [22]

| < |

Total |

TKT D.10 |

TKT D.5 |

TKT H.4 |

TKT G.19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

In contrast, let us secondly select the sporadic part of the coclass graph for demonstrating that another way of attaching additional arithmetical structure to descendant trees is to display the counter of hits of a realized vertex by the second -class group of fields with absolute discriminants below a given upper bound , for instance . With respect to the total counter of all complex quadratic fields with -class group of type and discriminant , this gives the relative frequency as an approximation to the asymptotic density of the population in Figure 12 and Table 3. Exactly four vertices of the finite sporadic part of are populated by second -class groups :

Comparison of various primes

Now let and consider complex quadratic fields with fixed signature and p-class groups of type . The dominant part of the second p-class groups of these fields populates the top vertices of order of the sporadic part of the coclass graph , which belong to the stem of P. Hall's isoclinism family , or their immediate descendants of order . For primes , the stem of consists of regular p-groups and reveals a rather uniform behaviour with respect to TKTs and TTTs, but the seven -groups in the stem of are irregular. We emphasize that there also exist several ( for and for ) infinitely capable vertices in the stem of which are partially roots of coclass trees. However, here we focus on the sporadic vertices which are either isolated Schur -groups ( for and for ) or roots of finite trees within ( for each ). For , the TKT of Schur -groups is a permutation whose cycle decomposition does not contain transpositions, whereas the TKT of roots of finite trees is a compositum of disjoint transpositions having an even number ( or ) of fixed points.

We endow the forest (a finite union of descendant trees) with additional arithmetical structure by attaching the minimal absolute discriminant to each realized vertex . The resulting structured sporadic coclass graph is shown in Figure 13 for , in Figure 14 for , and in Figure 15 for .

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Template:Cite book

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite book

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ Template:Cite journal

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Template:Cite journal